The Flying Scotsman: How the first 100mph locomotive became the most famous train in the world

The first train to officially hit 100mph may not even have been the first, and didn't hold the rail speed record for long; yet a century later its legend is undimmed. Jack Watkins celebrates the Flying Scotsman.

The most resonant name in British railway history, Flying Scotsman was officially the first locomotive in this country to clock 100mph, in 1934. Her 40 years in service encompassed the nationalisation of the railways in 1948 and she is synonymous with the days when steam was still king and the importance of a properly funded rail industry was recognised at the highest levels.

Yet, when the engine first rolled out of Doncaster Works in 1923, it was simply No 1472, only the third of 79 A1 class Pacific steam express locos built for the newly established London and North Eastern Railway (LNER) by its chief mechanical engineer, Nigel Gresley.

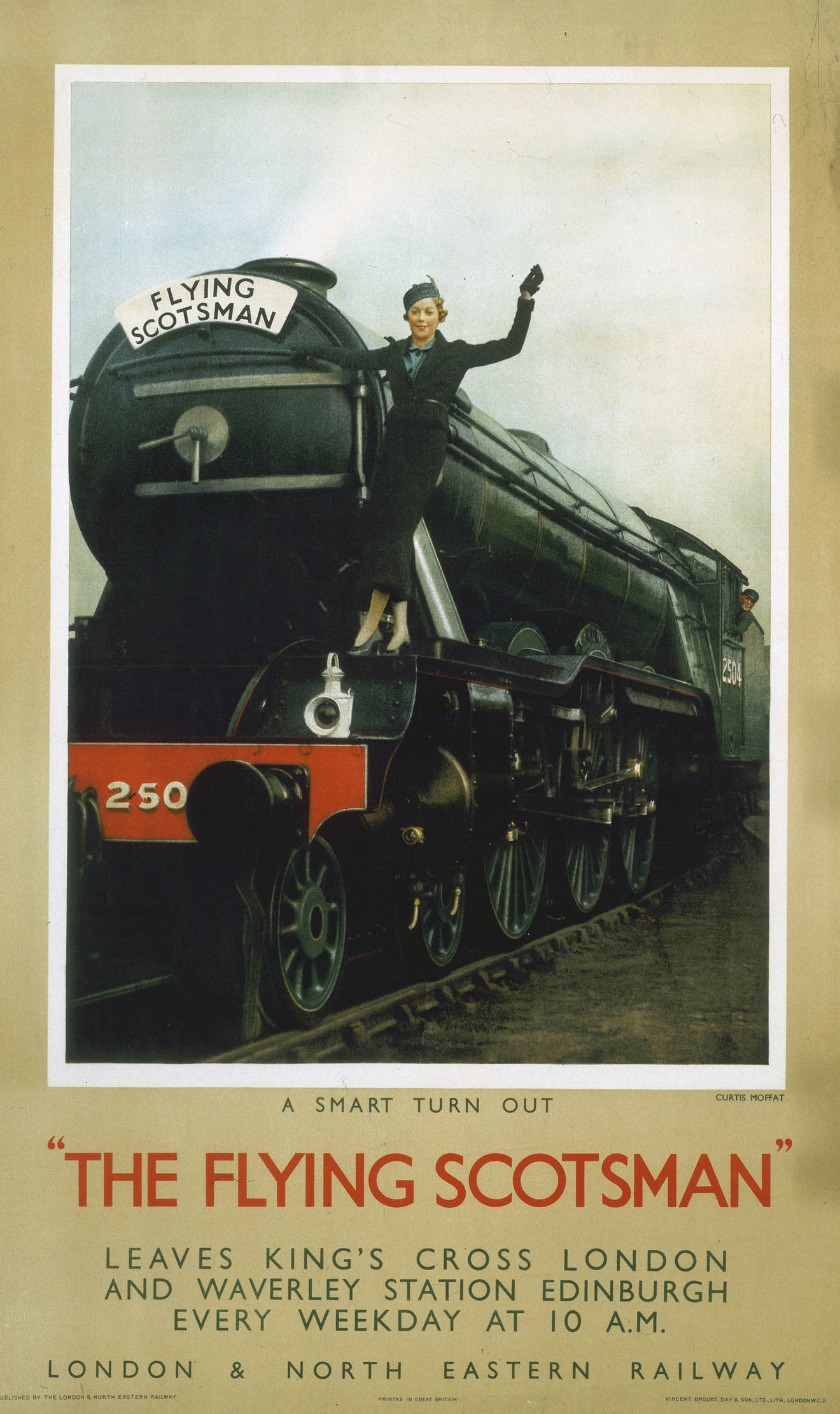

It is often forgotten that the terms the ‘Special Scotch Express’ or the ‘Flying Scotchman’ had been in popular usage for some time before that point. They were used to describe the 10am train running between London King’s Cross and Edinburgh Waverley, a service that dated back to the 1860s.

The official adoption of the honorific Flying Scotsman, echoing the tradition of American railroad companies, which gave names to their most powerful engines, was partly a marketing ploy.

In 1924, No 1472 (renumbered 4472) was chosen to represent the LNER at an international exhibition that ran from April to October of that year at the Empire Stadium, Wembley, in north-west London, promoting the industrial and artistic output of the British Empire. The display attracted more than 26 million visitors and was the ideal showcase for the ambitious railway company. Proudly bearing the company crest and painted a striking apple green, the locomotive entered the show billed as ‘the most famous train in the world’.

However, it would not be until 1928 that the name started appearing in timetables. Earlier express trains on the London to Edinburgh east-coast route had still made stoppages. In 1927, the A1 Pacific Flying Fox ran non stop from London to Newcastle; the LNER’s rival, the London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS), which operated the west-coast route from London Euston into Scotland, was running a train over a slightly longer non-stop distance between Euston and Carlisle.

In 1928, Flying Scotsman was fitted with new corridor tenders, which enabled a new crew to take over without requiring the train to stop. On May 1 of that year, with the name Flying Scotsman now borne on the headboard, the engine hauled the first ever non-stop London to Edinburgh service (as opposed to a one-off run), in the process reducing the journey time to eight hours.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The modifications in design that enabled Flying Scotsman to achieve this also gave her greater speed potential. At a time when there was interest in providing a high-speed rail service utilising diesel power, a test run was conducted with steam engines. In 1934, Flying Scotsman clocked 100mph on a run between London and Leeds. Pulling six coaches weighing 208 tons, this was achieved on a stretch of line just outside Little Bytham, Lincolnshire, for about 600 yards. Speed-measuring equipment carried on the train enabled the speed to be properly recorded.

City of Truro, a Great Western Railway locomotive, was among the trains to have an earlier claim to have passed the 100mph mark. However, it is Flying Scotsman that has entered the history books as the first verifiably recorded instance. Almost completely forgotten is the fact that, only a year later, the No 2750 Papyrus, another of Gresley’s Pacifics, surpassed it, achieving a speed of 108mph over the same stretch of track. The steam engine record would go on to be claimed by another of Gresley's engines, however. Mallard took the steam engine speed record with a 126mph run in 1938 — claiming it from a German engine — and has retained it ever since. Both Mallard and Flying Scotsman carried on in service until 1963.

The Flying Scotsman: How contemporaries and historians see one of history’s great locomotives

‘Mr Gresley’s splendid engine has certainly made new records and demonstrated that coal can still hold its own against oil in railway traction. It has shown conclusively that great accelerations are possible in British railway services’ ‘The Meccano Magazine’, 1935‘Flying Scotsman is, for many people, the defining icon of the steam age, and its exploits in the steam era and its years in preservation never fail to enthral’ Robin Jones, ‘A History of the East Coast Main Line’‘Long, lithe and handsome, it was a design that combined grace and power, and it was the perfect advertisement for the new railway company that aspired to be the best in the land’ Bob Gwynne, ‘The Flying Scotsman, The Train, The Locomotive, The Legend’

How to see The Flying Scotsman

Flying Scotsman was saved for the nation following a high-profile campaign in 2004 led by the National Railway Museum in the centre of York. The centenary year of 1923 is being marked by a series of events at the York museum, a visit to the engine’s native Doncaster (at the Danum Gallery) and appearances on heritage railways around the country.

If you see her, she'll be dark green; but it wasn't always so. Flying Scotsman was painted apple green in her record-breaking heyday, underwent subsequent colour changes, including black during wartime, blue with the nationalisation of the railways and, by the time of her retirement from service in 1963, British Rail green.

If you get to see Flying Scotsman for the first time, her profile may seem strangely familiar. In the Revd W. Awdry’s railway stories, Gordon the Big Engine, the proud, often snooty loco who considers it his absolute right to pull the express, was apparently an experimental precursor for the Gresley Pacific locos, according to Awdry’s The Island of Sodor, Its People, History and Railways (1987), which sought to explain the background to the ‘Railway Engine’ series and the credibility of the fictional settings.

In Focus: Mallard, the steam locomotive that's a true British masterpiece

Sir Nigel Gresley's Mallard steam locomotive is one of the great pieces of 20th century engineering. Jack Watkins tells its

Somerset born, Sussex raised, with a view of the South Downs from his bedroom window, Jack's first freelance article was on the ailing West Pier for The Telegraph. It's been downhill ever since. Never seen without the Racing Post (print version, thank you), he's written for The Independent and The Guardian, as well as for the farming press. He's also your man if you need a line on Bill Haley, vintage rock and soul, ghosts or Lost London.

-

Jungle temples, pet snakes and the most expensive car in the world: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 14, 2025

Jungle temples, pet snakes and the most expensive car in the world: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 14, 2025Mondays's quiz tests your knowledge on English kings, astronomy and fashion.

By James Fisher

-

Welcome to the modern party barn, where disco balls are 'non-negotiable'

Welcome to the modern party barn, where disco balls are 'non-negotiable'A party barn is the ultimate good-time utopia, devoid of the toil of a home gym or the practicalities of a home office. Modern efforts are a world away from the draughty, hay-bales-and-a-hi-fi set-up of yesteryear.

By Annabel Dixon

-

10 of Scotland’s most magical white sand beaches

10 of Scotland’s most magical white sand beachesWhat better day to celebrate some of Scotland's most stunning locations than St Andrew's Day? Here's our pick of 10 of the finest white sand beaches in the country.

By Country Life

-

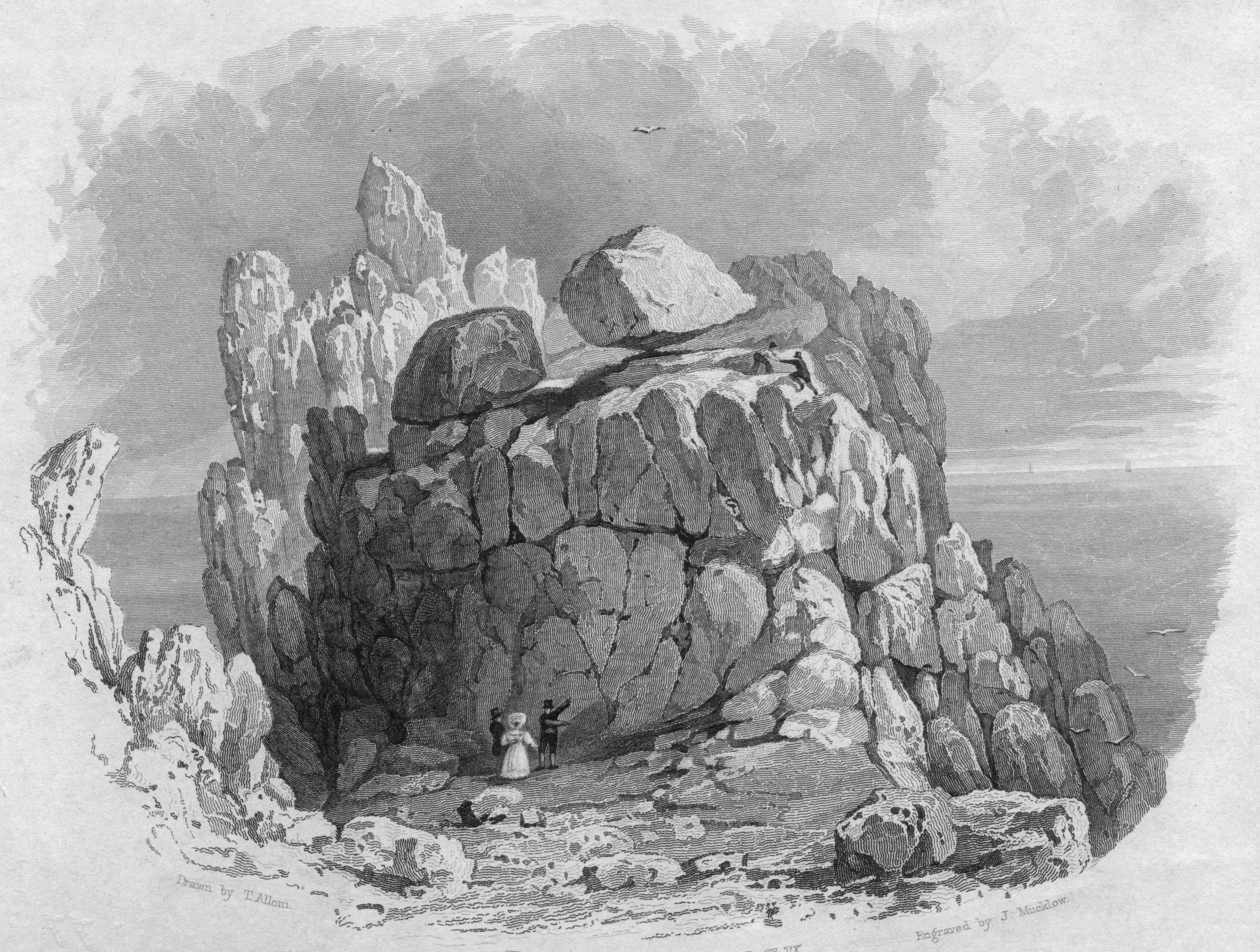

Curious Questions: Who dislodged Britain's most famous balancing rock?

Curious Questions: Who dislodged Britain's most famous balancing rock?A recent trip to Cornwall inspires Martin Fone to tell the rather sad story of the ruin and restoration of one of Cornwall's great 19th century tourist attractions: Logan Rock at Treen, near Land's End.

By Martin Fone

-

Henley Festival: 13 things you'll see at the 'posh Glastonbury'

Henley Festival: 13 things you'll see at the 'posh Glastonbury'Revellers in ball gowns and dinner jackets, turning up on board £200,000 boats to dance and party while knocking back magnums of vintage champagne? It can only be the extraordinary Henley Festival, the high-end musical extravaganza that's a sort of Glastonbury-on-Thames for the (very) well heeled. We sent Emma Earnshaw along to see what it was like.

By Emma Earnshaw

-

The best open air theatres in Britain

The best open air theatres in BritainAmid the sweet chestnuts, walnuts and cobnuts of a Suffolk farm, a natural amphitheatre has been transformed into a glorious sylvan venue for touring companies to tread Nature’s boards. Jo Cairdv pays a visit to the mesmerising Thorington Theatre, and picks out three more of the finest outdoor performance venues in Britain.

By Toby Keel

-

Alexandra Palace: How it's survived fires, bankruptcy and even gang warfare in 150 years as London's 'palace of the people'

Alexandra Palace: How it's survived fires, bankruptcy and even gang warfare in 150 years as London's 'palace of the people'Alexandra Palace has suffered every imaginable disaster, yet remains enduringly popular even a century and a half after its official grand opening. Martin Fone takes a look at the history of one of Britain's great public buildings.

By Martin Fone

-

Berwick-upon-Tweed, Northumberland: The spectacular border town with a castle that changed hands 13 times

Berwick-upon-Tweed, Northumberland: The spectacular border town with a castle that changed hands 13 timesBerwick-upon-Tweed spent centuries as a pawn in Anglo-Scottish conflict; today, it's a charming border town with spectacular sights. Clive Aslet takes a look.

By Clive Aslet

-

Ewelme, Oxfordshire: The medieval almshouses set up by Chaucer's grand-daughter and still running today

Ewelme, Oxfordshire: The medieval almshouses set up by Chaucer's grand-daughter and still running todayCountry Life's 21st century Grand Tour of Britain stops off at the remarkable church and almshouses at Ewelme, Oxfordshire.

By Toby Keel

-

Laxton, Nottinghamshire: The 21st century village still using a medieval farming system

Laxton, Nottinghamshire: The 21st century village still using a medieval farming systemOpen field strip farming has almost entirely disappeared from Britain in the past 1,000 years — though there is one great exception: Laxton.

By Clive Aslet