From Shetlands to Shires: Native horse breeds of Britain

From Shetlands to Shires, it’s horsepower that helped make this country great. We celebrate the wonderful local diversity of our native breeds.

For a small, island nation, we have a remarkable diversity of domestic animals and our lives, and the equine gene pool, are the richer for it. From Shires to Shetlands, Highlands to Hackneys, here are 16 native horse breeds of Britain.

1. Shetland

Little pony, big personality: the breed that’s a gift to cartoonists for its short stature, bustling rump and piercing gaze from under a bouffant forelock is integral to many people’s earliest riding memories—and not always in a good way. The Shetland is still a much-loved element of local culture in its remote homeland, but, as with so many of our domestic animals, it was Queen Victoria who can be credited for boosting its popularity as a pet and as a riding and driving pony. The stud book—the first for a native pony—was started during her reign, in 1890. www.shetlandponystudbooksociety.co.uk

2. Eriskay

This extremely rare pony from the Western Isle owes its existence to a group of people, comprising a priest, a doctor, a vet, a scientist and crofters, on Eriskay who, in the early 1970s, made a concerted effort to save the original crofter’s pony, a smaller, lighter-boned, less well-known relation of the Highland, which had dwindled to some 20 animals due to mechanisation and the migration of islanders to the mainland. There are now about 420 of these mostly grey ponies in the world. www.eriskaypony.com

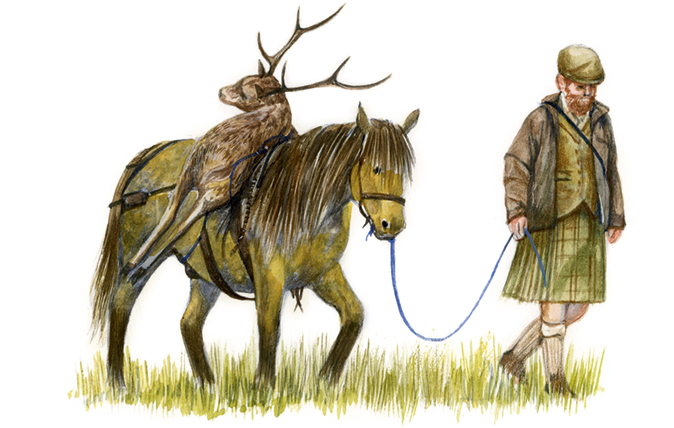

3. Highland

Theories abound about the Highland’s ancestry, but it’s thought that this kindly, chunky, sure-footed breed, often an attractive golden or mousey dun colour with a black ‘eel’ stripe from withers to rump and ‘zebra’ legs, was the result of crossing the Eriskay pony with a heavy farm breed, such as the Clydesdale, to work the land, with a dose of Arab, Percheron and roadster bloodlines along the way. Again, Victoria championed the breed—she famously liked to ride one in stately fashion around Balmoral—as did painters such as Landseer, who recorded the ponies placidly lugging dead stags down from the hill. www.highlandponysociety.com

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

4. Clydesdale

Scotland’s giant, lavishly feathered farm horse was developed in the Clyde Valley in the 18th century by John Paterson of Lochyloch and the 6th Duke of Hamilton. They crossed draught mares with Flemish stallions, which was so successful that, at one stage, there were some 140,000 horses in the area: in 1911, one, Baron of Buchlyvie, made £9,500 at public auction in Ayr and 1,617 stallions were exported—Clydesdales were used to deliver the first case of beer from the Anheuser-Busch brewery in St Louis after prohibition was lifted in the USA in 1933—but, by 1949, the UK population was down to 80. www.clydesdalehorsesociety.com

5. Fell and Dales

These similarly built, rugged, mostly black ponies—the Dales is slightly larger and stronger, with a more rounded action —were crucial to the mining industry as pack-horses. Over the centuries, they’ve ploughed, pulled sledges, crossed the country bearing wool, food and ores and even hunted wolves; nowadays, they’re used for forestry and shepherding work. Both ponies, which still roam the east and west sides of the Pennines from which they originate, have become popular for riding and driving—a Fell, Townend Schubert, was supreme champion Mountain & Moorland at Olympia in 2015 and the breed, with its ground-devouring stride, can be seen in the old Cumberland sport of trotting. www.fell ponysociety.org.uk; www.dalespony.org

6. Cleveland Bay

Originally known as Chapman horses—they carried the wares of the chapman (travelling salesman)—these handsome, clean-legged animals came into their own as royal coaching horses during Elizabeth I’s reign and they’re still used on state occasions. The weight-carrying horse, always a solid, rich, bay colour, has been considerably improved through selective breeding since it transported wool from farm to factory in the North-East—Thoroughbred blood has produced useful sport horses and smart gents’ hunters, although the pure-bred Cleveland bay is now in short supply. www.clevelandbay.com

7. English Thoroughbred

The importation into Yorkshire and Derbyshire of three foundation stallions from the Middle East—the Byerley Turk, in the 1680s, the Darley Arabian (1704) and the Godolphin Arabian (1729)—established the genetic pool that’s the root of a racing and breeding industry and tradition that is the envy of the world. www.weatherbys.co.uk

8. Hackney

The Tiller Girl of the horse world, with its fastidious, high-stepping gait—hackney comes from the French haquenee: a horse with a comfortable trot—evolved in the 1700s when Arab blood was introduced to create a sought-after flashy driving horse or pony in the Regency period and a superior roadster, a horse bred to race along roads, a sport particularly popular in East Anglia. It was decided there should be a register of English trotting horses, a task taken on by Henry F. Euren, Editor of the Norwich Mercury, who started the Hackney Stud Book Society in 1883. www.hackney-horse.org.uk

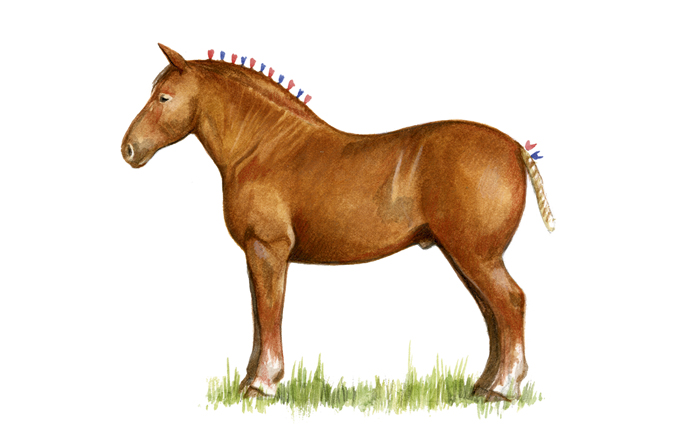

9. Suffolk Punch

The magnificent breed, more compact than other heavy breeds, is considered Britain’s oldest heavy horse and is subject to strict rules—the colour must be chesnut (historically, seven shades were acceptable: dark liver, dull dark, light mealy, red, golden, lemon and bright)—chesnut must be spelt without the ‘t’ in the middle —and, although some white is allowed on the head, markings on the fetlock are forbidden in breeding stallions. All lines trace back to a stallion known as Crisp’s Horse of Ufford, after its owner Thomas Crisp, which was foaled in 1768. www.suffolkhorsesociety.org.uk

10. Shire

By the 18th century, breeders were beginning to separate work horses into faster, lighter, sporting types and the heavier horses needed for farm work. The huge, powerful Shire, at about 17.2hh and 22cwt, came into its own, first, with the invention of Jethro Tull’s seed drill in 1701 and the switch from oxen to horses, then the Victorian expansion in transport and industry, and was used to pull barges along the developing network of canals, as well as the first omnibuses and trams, and for rubbish collection and brewery drays. www.shire-horse.org.uk

11. Welsh Mountain

Wales’s national ponies, which can be any colour, although are invariably envisaged as grey, divide into four categories: Sections A, B, C (of cob type) and D (cob) according to size. The showy little Section A, with its pretty, dished, Disney face and big, dark eyes, is every small girl’s dream, yet the entire breed was nearly wiped out thanks to Henry VIII. He decreed that, because the wild ponies were a nuisance to farmers, the ones too small for war should be culled. By the 18th century, however, Welsh farmers realised what a desirable commodity they had on their doorstep and began breeding them to sell at fairs. http://wpcs.uk.com

12. Welsh cob

The versatile, feisty Welsh cob is referred to in 930, in the laws of Hywel the Good, who divided the local equines of his kingdom in south-west Wales into three groups: the Palfrey (riding pony), Rowney or Sumpter (packhorse) and Equus Operarius (working cob). The true Welsh cob has a thrusting, powerful gait with a high knee action; in showing classes, the human handler will often mirror the cob’s gait to hilarious effect. http://wpcs.uk.com

13. Exmoor

Local pride and effort have saved our oldest and arguably most consistently pure-bred native pony, uniform in its compact, weatherproof physiology, mealy nose and hooded toad eyes that keep out the rain, although this is becoming a challenge on open moorland. The breed was nearly destroyed when abandoned during the Second World War, but there are now 11 privately owned herds running wild on the moor, plus two owned by the Exmoor National Park Authority, and preservation work is continuing with a project to create a genetic database. www.exmoorponysociety.org.uk

14. Dartmoor

Sadly, this pony is often misrepresented: those seen roaming the tors and bogs of Dartmoor are rarely the pure strain—a good-looking, quality child’s riding pony, now mostly produced, with great care, by private breeders—but are more likely to be random, often unwanted hill ponies, mistakenly described in the media as Dartmoor ponies. In fact, the breed society has a stringent registration and stallion-grading procedure, although local ponies that show true breed qualities can be registered as having ‘heritage’ status. www.dartmoorponysociety.com

15. New Forest

Another pony with a complicated identity, the New Forest is bound up in ancient tradition: the ponies grazing freely beside roads and on village greens are owned by people who have ‘the rights of common pasture’, but, like the Dartmoor, they are not necessarily true natives, due to the difficulty of maintaining purity in open country. However, a pony sired by a registered stallion—10–15 are released into the forest each season—and born in the open can be registered as ‘forest-bred’. The classic New Forest, a handsome, fast and athletic mini-Thoroughbred, which was raced in the 19th century and used as an army remount in the 20th, has been imbued over time with Spanish, Thoroughbred and Arab blood—Marske, sire of the legendary 18th- century racehorse Eclipse, once stood in the New Forest and Queen Victoria loaned two Arab stallions to the verderers. www.newforestpony.com

16. Connemara

The ‘Connie’, one of the natives most pleasing on the eye, is a valuable Irish export; there are spin-off societies in 15 countries, from New Zealand to Finland, and, at last month’s sale at Clifden in Co Galway, 110 ponies were sold overseas. Prized for its intelligence, hardiness and sure-footedness, with a touch of quality that harks back to an injection of Spanish blood in the Middle Ages, it’s renowned as a good jumper and is the pony of choice—especially when crossed with a Thoroughbred —for ambitious eventing teenagers or the veteran horseman looking to downsize. Henrietta Knight, former Gold Cup-winning trainer, is a noted Connemara aficionado. www.cpbs.ie

On the critical list

- The Rare Breeds Survival Trust lists the Cleveland Bay, Hackney horse and pony, Dales pony, Suffolk Punch and Eriskay pony as ‘critical’ (fewer than 300 breeding mares in existence)

- Dartmoor and Exmoor ponies are listed as ‘endangered’ (300–500)

- The Clydesdale, Fell and Highland are categorised as ‘vulnerable’ (500–900)

- The Shire is ‘at risk’ (900–1,500) H The New Forest is ‘minority’ (1,500–3,000)

British rare breeds we must save

Forty years ago, some far-sighted farmers realised that traditional British farm animals were dying out and a precious gene pool

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Your child's first pony: A survival guide for parents

The request for a pony is dreaded by many parents, but, with the right help and the right animal, the

-

Two quick and easy seasonal asparagus recipes to try this Easter Weekend

Two quick and easy seasonal asparagus recipes to try this Easter WeekendAsparagus has royal roots — it was once a favourite of Madame de Pompadour.

By Melanie Johnson

-

Sip tea and laugh at your neighbours in this seaside Norfolk home with a watchtower

Sip tea and laugh at your neighbours in this seaside Norfolk home with a watchtowerOn Cliff Hill in Gorleston, one home is taller than all the others. It could be yours.

By James Fisher