Interview: José Carreras

Tessa Waugh is charmed by José Carreras: a man whose life is played out like an operatic tale where his final philanthropic act could be his finest yet

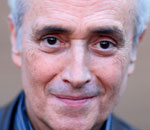

In the padded luxury of his hotel room, José Carreras looks tired and drawn. Now 62, this courteous, subdued man seems a world away from the flamboyant performer who is recognised worldwide as one of the greatest tenors of our time, the man whose voice wowed football stadiums and inspired legions of female fans to dream about another of his qualities those famous eyes with equal fervour. However, his weariness is hardly surprising.

A few nights before, he’d been performing at Proms in the Park, and his punishing schedule of 50 to 60 concerts a year shows no sign of letting up. He says that if he were told he could only sing for one more year, he wouldn’t change a thing. ‘I’ve had 38 years of professional singing, so an extra year would be a nice tip.’ But a plan to retire eludes him: ‘I know it has to end, and it’s going to happen sooner or later, but the closer I see this end, the more I enjoy what I’m doing.’

It’s easy to understand Mr Carreras’ reluctance to call it a day. Singing has been his life. He debuted at the world’s most prestigious opera houses in his twenties, and performed all the great operatic roles before the age of 30. With 60 operas and 150 recordings under his belt, he has worked hard, and if he hadn’t been diagnosed with leukaemia, aged 40, the pace probably would have continued unchecked. Now, he has a clean bill of health, but the effect of the illness has been far-reaching.

Small and immaculate, he leans forward in his chair to say: ‘When I came out of hospital, I felt so much in debt to science and society and I thought I had to do something.’ He set up the José Carreras International Leukaemia Foundation in 1988, with the aim of making the disease 100% curable for all sufferers. Twenty years later, the foundation is raising roughly €25 million a year to support scientific research, but he acknow-ledges the success modestly: ‘We’re doing a good job.’ If he seems apprehensive about life without singing, the foundation offers a focus for the future: ‘It’s a very important goal in my life, and the day I stop singing, I will dedicate myself totally to that.’

Although not a religious man, maturity has brought a desire for what he describes as ‘moral rigour’. ‘I feel more responsible,’ he says. When I ask if this rigour has affected his attitude towards women, he brushes the question aside with a devilish twinkle: ‘Oh no, no, no, I don’t mean the ladies.’ Mr Carreras has, in the past, described himself as ‘compulsive’, but he’s been famously quiet on the collection of beautiful women who have wafted in and out of his life. He married his second wife, Jutta Jager, two years ago. Although his face in repose looks rather melancholy, there are moments when the passionate stage persona shines through. When I mistakenly suggest that his father was French, he almost jumps to his feet to declare ‘I am Catalan’, and I half expect the orchestra to start up and for him to burst into song. He softens when he talks about his two children, from his first marriage, and his three grandchildren. ‘My children didn’t show a particular talent for music. Let’s hope for my grandchildren.’

When he isn’t working, he likes to enjoy the things that his busy life has lacked, ‘to see my friends, to play a silly game of cards, to talk about football and women and politics or religion’. Naturally, he sees the death of Luciano Pavarotti as a great loss: ‘Not to listen to his voice live, it’s a frustration, but I miss him more as a friend. He was like an older brother to me, and I always had a great time with him, both with the profound, important things and in the entertaining parts of life.’ If José Carreras’ life bears any similarity to the great operatic tales loves lost and won, illnesses overcome this final act, with its philanthropic emphasis, could be his finest yet.

José Carreras will be performing at a gala concert in aid of the José Carreras International Leukaemia Foundation at the Royal Albert Hall on December 11. For tickets, telephone 020–7589 8212 or visit www.royalalberthall.com

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

380 acres and 90 bedrooms on the £25m private island being sold by one of Britain's top music producers

380 acres and 90 bedrooms on the £25m private island being sold by one of Britain's top music producersStormzy, Rihanna and the Rolling Stones are just a part of the story at Osea Island, a dot on the map in the seas off Essex.

By Lotte Brundle

-

'A delicious chance to step back in time and bask in the best of Britain': An insider's guide to The Season

'A delicious chance to step back in time and bask in the best of Britain': An insider's guide to The SeasonHere's how to navigate this summer's top events in style, from those who know best.

By Madeleine Silver