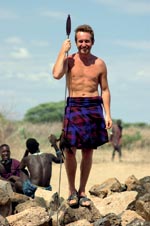

Interview: Bruce Parry

The 38-year-old presenter of the popular BBC programme 'Tribe' has visited 15 tribes, living with each for a month at a time after which – understandably -- he craves clean sheets and an iPod

It is very odd seeing Bruce Parry wearing a shirt, more so even than seeing him in a shiny London hotel. And he is tiny. It is the kindly, lived-in face and energetic personality that are most recognisable from the BBC television series Tribe: the people who watch his programmes are 'sooo nice', the tribes he visits are 'sooo lovely'. Bruce is a West Country boy. His CV navigates Wells Cath-edral School, the Marines, leading expeditions in the jungle, pop videos and children's television. During the course of making Tribe (now in its third series), he has visited 15 tribes, living with each for a month at a time. And when he has a sago thorn pushed through his septum, or takes a giant dose of hallucinogen, he does much to enliven office chats across the land. But Bruce is dismissive about the things that bring him 'a weird credibility' with the public. 'Drinking blood is no big deal. A locust tastes like a prawn when you've been eating nothing but Sago.' He never rushes back to the film crew's camp for bolognese and beer. 'Early on, I knew that if I did so, I'd be neglecting the people I was supposed to be getting to know.'

It is the bits that don't make good television that he finds the hardest. 'The fire goes down, and I can't even communicate with hand signals. So I'm lying there, unable to sleep, with a naked guy on one side, a baby on the other, picking ants off myself. It's boring,' he says, with passion. But this doesn't detract from what he values about these experiences 'family values, stress-free living and community spirit'. Does he ever wish he could stay? 'I feel really sad answering this question, because after a month I do want clean sheets and an iPod. But I can take away a lot.' Is he introducing these elements into his own life? 'The irony is that I'm learning about these things, but my life is going in a completely different direction. I learn about stress-free living, and I have more stress. I learn about free time and have less.' I have to push him to get him to remember an occasion when relations broke down. 'One of my very strict rules is that I never come on to anyone.' Have you ever wanted to? 'Oh, of course.' Once, when he quiz-zed a group of women about their attitudes to men and sex, the director made a joke about his suitability as a husband.

'I think the word got around that I was chatting the girls up. I could tell that the men were treating me differently, but I soon got it back on track.' There have been criticisms of this kind of popularised anthropology, but Bruce is impatient with his detractors: the crew only goes where they are welcome, the tribes are always paid, and he never visits people who haven't met outsiders before. 'It's a romantic notion that we should keep all these pristine cultures as they are. They're human, and they should be allowed to do what they want provided that they are informed about the pitfalls.' It is a lesson he learned making Tribe. He admits to being 'quite naïve' in the early days, for example, counselling the Babongo in Gabon that they shouldn't allow a road to come to their village. He still seems genuinely distressed about this mistake: 'They were my friends, and they were telling me, "we want a road because we want goods to arrive". I had no right to tell them what to do.'

One of Bruce's favourite moments was when he asked members of the Kombai from Indonesia if they were interested in where he came from. 'We don't care because it's obviously rubbish', was the answer. It was a sentient point: 'I'm in a celebrity culture, and what is more twisted than that?' He craves time at home in his farmhouse in Ibiza. 'I'm 38 and single,' he adds, as if he was saying, 'I'm Bruce and I'm an alcoholic.' At the same time, he is delighted with the opportunities life has given him: 'What can be better than to feel like you're doing something positive? It's everyone's dream.'

'Tribe: Adventures in a Changing World' by Bruce Parry is published by Michael Joseph at £20

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

'Monolithic, multi-layered and quite, quite magnificent. This was love at first bite': Tom Parker Bowles on his lifelong love affair with lasagne

'Monolithic, multi-layered and quite, quite magnificent. This was love at first bite': Tom Parker Bowles on his lifelong love affair with lasagneAn upwardly mobile spaghetti Bolognese, lasagne al forno, with oozing béchamel and layered meaty magnificence, is a bona fide comfort classic, declares Tom Parker Bowles.

By Tom Parker Bowles

-

Country houses, cream teas and Baywatch: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 24, 2025

Country houses, cream teas and Baywatch: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 24, 2025Thursday's Quiz of the Day asks exactly how popular Baywatch became.

By Toby Keel