How cycling freed British people to enjoy the countryside once again

The arrival of the bicycle and tricycle opened up a thrilling freedom for the people of Britain.

On May 8, 1897, Country Life Illustrated carried a column on ‘Cycling’. It began: ‘There is little question in the minds of those who have had the opportunity of trying all branches of the sport of cycling that leisure touring is, beyond doubt, the best part of it.’

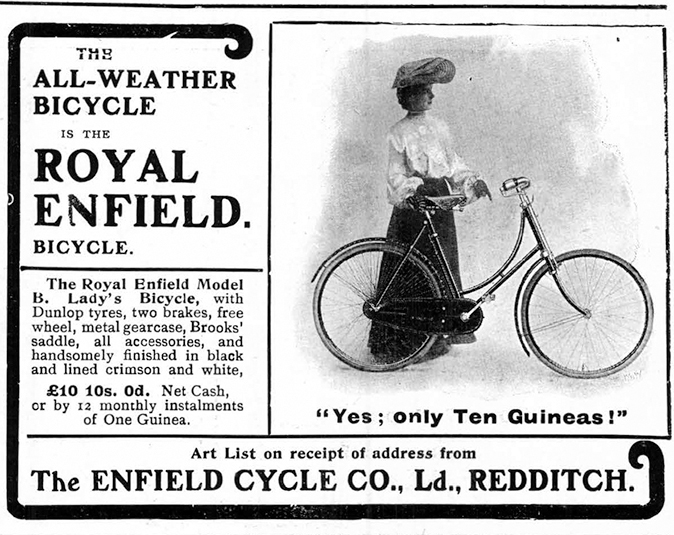

To demonstrate that the pastime was now fashionable, there was a photograph of Lady Norreys, sitting on her bicycle. The following week, the attraction was a photograph of Lady Cholmondeley on her machine.

Soon this was a regular column, Cycling Notes, written by The Pilgrim, offering useful advice on such things as cleaning a bicycle and recounting instances of the persecution of riders, such as when ‘a Preston cyclist was fined 5s and costs for furiously riding a bicycle in that town’.

Although the emancipation of the motor car was just beginning, with the Locomotives on Highways Act 1896, the world Country Life entered was not that of the internal-combustion engine, but that of the steam train – and the bicycle. The magazine was founded when the countryside beyond the railway was beginning to be explored by bicycles and tricycles, when cycling clubs (with their own special uniforms) flourished.

The Bicycle Touring Club was founded in Harrogate, North Yorkshire, in 1878 ‘to form a medium of mutual assistance for tourists, by giving each other information as to roads, hotels, sights and other matters of common interest in the pastime’. It was renamed the Cyclists’ Touring Club in 1883 to encompass tricyclists and, by 1886, it had more than 22,000 members.

The bicycle represented liberation, particularly for women. It enabled individuals and groups to tour Britain, admiring views and visiting monuments, churches and villages that the railway had rendered remote and it helped revive old coaching inns. In 1898, an article on ‘Typical English Villages’ looked at Broadway, Worcestershire, which was then almost inaccessible: ‘It is not easy to say who was the modern discoverer, or rediscoverer, of this beautiful and interesting old village. It must have needed some finding… We have a suspicion that the inartistic and unecclesiastical bicycle may have brought it again into notice.’

Even the magazine’s first fashion correspondent took to the roads, Mlle Sans-Gêne recounting in September 1897: ‘We went for a long bicycle ride this morning, arriving during its progress at a picturesque old church, where we wandered for half an hour endeavouring to decipher the inscriptions on old tombs, from which nearly all the brasses had been filched by the appreciative.’

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

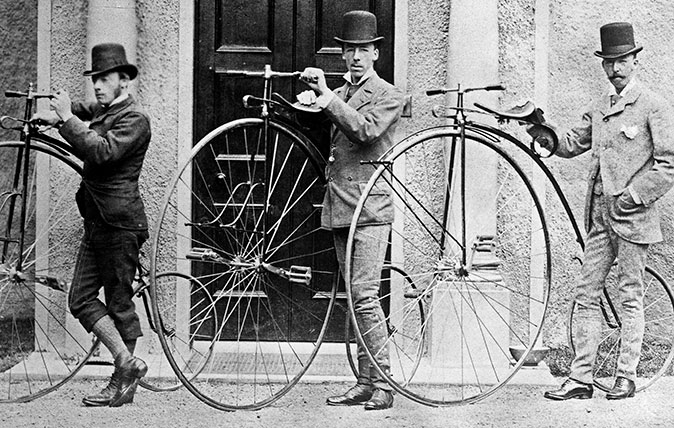

The first mass-produced bicycle, the Ordinary, now better known as the penny-farthing, arrived in the 1880s. The steerable front wheel had grown almost as high as a man and the back wheel was much smaller. They were unstable, as the saddle was above the high wheel, the pedals were fixed without a free wheel and the brake ineffective, so that the rider was easily flung over the handlebars from a painful height: the Ordinaries could only really be ridden by athletic men.

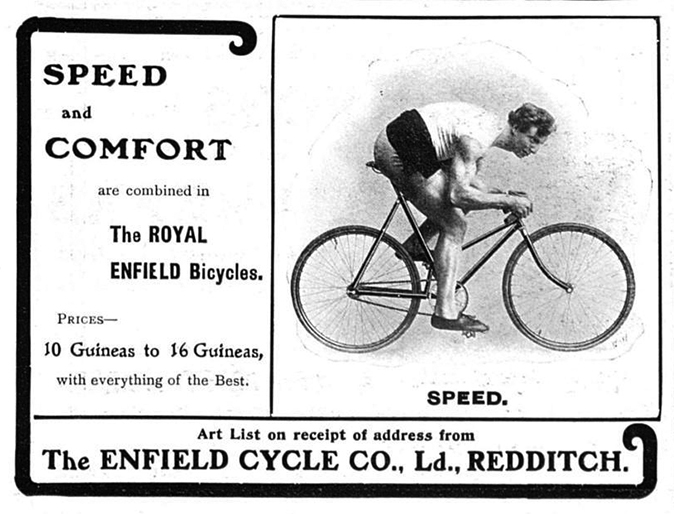

The advent of the staid tricycle, however, enabled women to ride as well and, between 1885 and 1891, the modern safety bicycle was developed by British manufacturers. These practical, easy-to-ride machines had a chain-driven rear wheel and, eventually, Dunlop pneumatic tyres.

Full skirts presented problems, but these could be overcome, as in Conan Doyle’s Adventure of the Solitary Cyclist, which deals with a bicycling mystery in rural Surrey concerning ‘the graceful girl sitting very straight upon her machine’.

Maps and guides were now needed – the last guide to Britain’s roads, Paterson’s Roads, had been published in 1826 and the ones that the traveller and antiquary would use for the next half century (Murray’s Handbooks or Baedeker) were organised according to railway lines. In 1882, a new guide was supplied in The Roads of England and Wales: An Itinerary for Cyclists, Tourists & Travellers, compiled by Charles Howard, a member of Wanderers’ Bicycle Club and the Cyclists’ Touring Club.

‘Our roads are in a state of transition,’ Howard noted. ‘After a life of nearly 200 years the turnpike trust system is doomed… the care of the roads being now transferred to the newly constituted County Councils.’ What may seem surprising today, now that tarmac is ubiquitous, is the extent to which road surfaces – often ‘macadamised’ with hard-packed small stones – were then determined by local geology.

Howard recorded that ‘undoubtedly the smoothest road surface is that made of gravel’, although it had ‘a tendency to become sandy, and in wet weather very heavy’. Flint roads, he thought, were best for wet weather and ‘limestone gives a good hard surface, but somewhat uneven, and, in wet weather, is liable to be greasy than merely soft or heavy, but is never dangerously so, like oolite’.

Oolite, in fact, was worst of all; in dry weather, it ‘makes a hard and tolerably good surface, but when wet it is almost impossible to ride upon it with safety’. Such information mattered to the roving wheelman perched on top of his penny-farthing.

Howard’s book reveals how decayed and dangerous many main roads were towards the end of Victoria’s reign. The road from Lewisham to Eltham, for instance, ‘is macadam all the way, and very bad and shaky; there is a long and stiff ascent to Eltham’. River Hill, south of Sevenoaks in Kent, was ‘very steep and winding’ and ‘not safe to ride down without a reliable brake’. On the west side of Exeter, there was ‘a very steep hill, quite impossible to ride up (and dangerous to ride down)’.

Perhaps most revealing about the decay of the road system is the description of the old main road from London to Glasgow between Kendal and Shap where ‘great care should be taken. The greater part of this stage is very bad, some of it being overgrown with grass and covered with loose stones, so that it is no better than a mere mountain track for miles’.

Some roads were good, however. ‘The road from Esher to Guildford is one of the finest near London, not only for the pretty and varied views of scenery it is bordered with, but also on account of the uniform goodness of its surface’ and from Belper to Matlock in Derbyshire, there was ‘beautiful scenery all the way… all the roads round Matlock have a good surface, and afford capital riding, but being hilly a good brake is required’.

It’s clear from the guide that scenery and landscape were presumed to be of as much, or more, interest to the cyclist than architecture. Nevertheless, country houses, churches and ancient monuments were listed, as were hotels and inns (with a notation of whether they had adopted the Cyclists’ Touring Club tariff).

The attractions of the great industrial cities were also recorded, not least those of Coventry, which ‘may be called the headquarters of bicycle manufacturing, and a visit to some of the great bicycle works will prove of interest to the tourist’.

The Roads of England and Wales paints a picture of a now lost world into which the pioneering bicycling tourist could venture. However, there were dangers beyond the state of so many roads. Bicyclists could be apprehended by policemen and fined by magistrates for speeding – my wife’s grandfather was fined sixpence for riding far too fast on a penny-farthing through Willingham in Cambridgeshire – and they could provoke the violent hostility of other road users, who would do their best to knock them over.

An early Country Life printed an alarming account of ‘gangs of roughs’ who preyed on lady cyclists: ‘One of their pleasant ways is to draw a rope across the cyclist’s path, to her certain misadventure, after which they proceed to insult, to threats, and, perhaps, to actual violence in order to make the unfortunate sufferer disgorge anything in the way of petty cash that she may happen to have about her.’

Even so, with all these vicissitudes, it must have been thrilling to be able to explore an enticing rural Britain beyond the railways, one that had been asleep for about half a century.

-

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attached

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attachedUpper House in Derbyshire shows why the Kinder landscape was worth fighting for.

By James Fisher

-

John Sutcliffe — The man, the myth and the paint-naming legend behind Dead Salmon and Elephant's Breath

John Sutcliffe — The man, the myth and the paint-naming legend behind Dead Salmon and Elephant's BreathBy Carla Passino