Curious Questions: Why do we call picture puzzles 'jigsaws'?

Jigsaws have been around since the 18th century and have gone through all sorts of iterations. Martin Fone traces their curious history.

Manufacturers of puzzles have been beneficiaries of the Covid-19 induced lockdown, bringing board games to the bored, you might say. Ravensburger, the global market leaders in the world of jigsaw puzzles, reported that sales in the early days of social isolating had soared by 370%. Particularly popular, they found, were those featuring cosy fireplace scenes and pictures of exotic locations, providing the player a safe haven in which to escape from this troubling world and the rosy glow of satisfaction when the final piece is inserted.

This resurgence in interest in jigsaws should perhaps not take us by surprise. As a relatively cheap form of escapism, jigsaws were enormously popular in the United States in the 1930s during the Great Depression. Fads are often cyclical.

A jigsaw is a picture cut up into variously shaped interlocking pieces, the object of the exercise being to reconstitute the picture, thereby solving the puzzle. A jig saw, on the other hand, is a tool with a reciprocating blade, one that works on a push and pull principle, and is used to cut shapes and irregular curves into materials such as wood and metal.

Reciprocating saws in themselves were nothing new. A sawmill in Hieropolis used one powered by a waterwheel as far back as the second half of the 3rd century BC. However, a jig saw seems to have been a fairly modern development, the earliest use of the phrase appearing in an American patent application submitted by Carlyle Whipple of Lewiston in Maine on January 13, 1857 for ‘a method of hanging and operating reciprocating saws’ that could be used ‘for small scroll or jig saws’. Knight’s American Mechanical Dictionary, published in various volumes between 1877 and 1884, contain some of the earliest descriptions and illustrations of jig and scroll saws. It is fair to assume that jig saws began to gain traction in the second half of the 19th century.

The story of what we now know as jigsaws began a century earlier. In 1762 a London based map engraver by the name of John Spilsbury had a bit of a brainwave to brighten up the lives of schoolchildren. He pasted one of his master maps on to a piece of wood and then laboriously cut around the borders of each of the countries.

Taking the pieces to a local school, he set the pupils the task of reassembling the map from the pieces — a welcome relief, I am sure, from the tedium of learning by rote that made up the majority of their lessons and an exciting way of understanding the relative positions of the European states to each other.

Spilsbury’s dissected maps proved a hit and soon attracted imitators. They were used by the royal governess, Lady Charlotte Finch, to teach the children of King George III and Queen Charlotte the rudiments of geography. Soon puzzles emerged showing religious scenes and rural settings such as farmyards, dissected puzzles all primarily aimed at schoolchildren. An adult audience was not really found until the late 19th century when three significant developments boosted the fortunes of the picture puzzle business.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Lithographic printing techniques had improved by leaps and bounds, allowing puzzle manufacturers to produce illustrations which were brightly coloured, sharper, and showing much finer detail. Plywood, layers of wood stuck together, became available, offering a much cheaper and more pliable form of material than the original solid pieces of wood.

The game changer, though, was the development of the jig saw and, in particular, one powered by a foot treadle. Puzzle designers were able to cut ever more intricate shapes with which to tease and perplex the players. As well as being more accurate, these saws were quicker which meant that more puzzles could be produced, and their price could be reduced. So synonymous did the puzzles become with the tool that had revolutionised their manufacture that they adopted their name. The jigsaw puzzle had arrived.

Despite the improvement in production techniques, puzzles were still relatively expensive: a 500-piece one could easily cost a tenth of a worker’s average monthly wage. They became a staple feature at a weekend house party in the early 20th century, but they would have looked strange to the modern player. The pieces did not interlock, which spelt disaster if the table was knocked, there were no transition pieces, the cut of the shapes followed the edges of a single colour, and the boxes did not include an illustration of the completed picture. The only clue to what image the pieces made was contained in the title.

Parker Brothers, the game manufacturer, made two further innovations with their Pastime puzzles, introducing figures into their pictures, thus making them marginally easier to complete, and using pieces that interlocked with each other. So popular did their jigsaws become that in 1909 they devoted the whole of their factory to their manufacture.

Jigsaw mania really took hold of America during the Depression, with around 10 million puzzles sold a week. To make the puzzles affordable, they were printed on die-cut cardboard. For those who still could not afford them, enterprising libraries and stores would hire them out for a few coppers. Discovering you had brought home a puzzle with some pieces missing was an experience akin to borrowing a book and finding the last page torn out. Magazines containing a weekly cardboard puzzle appeared on newsstands from 1932, retailing at just 25 cents — $4 or so in today’s terms — with titles such as Jig of the Week, Picture Puzzle Weekly and Jiggers Weekly. Retailers cashed in, offering a free jigsaw, the picture of which would include their advertising slogan, brand, or the product, with every purchase of a certain item.

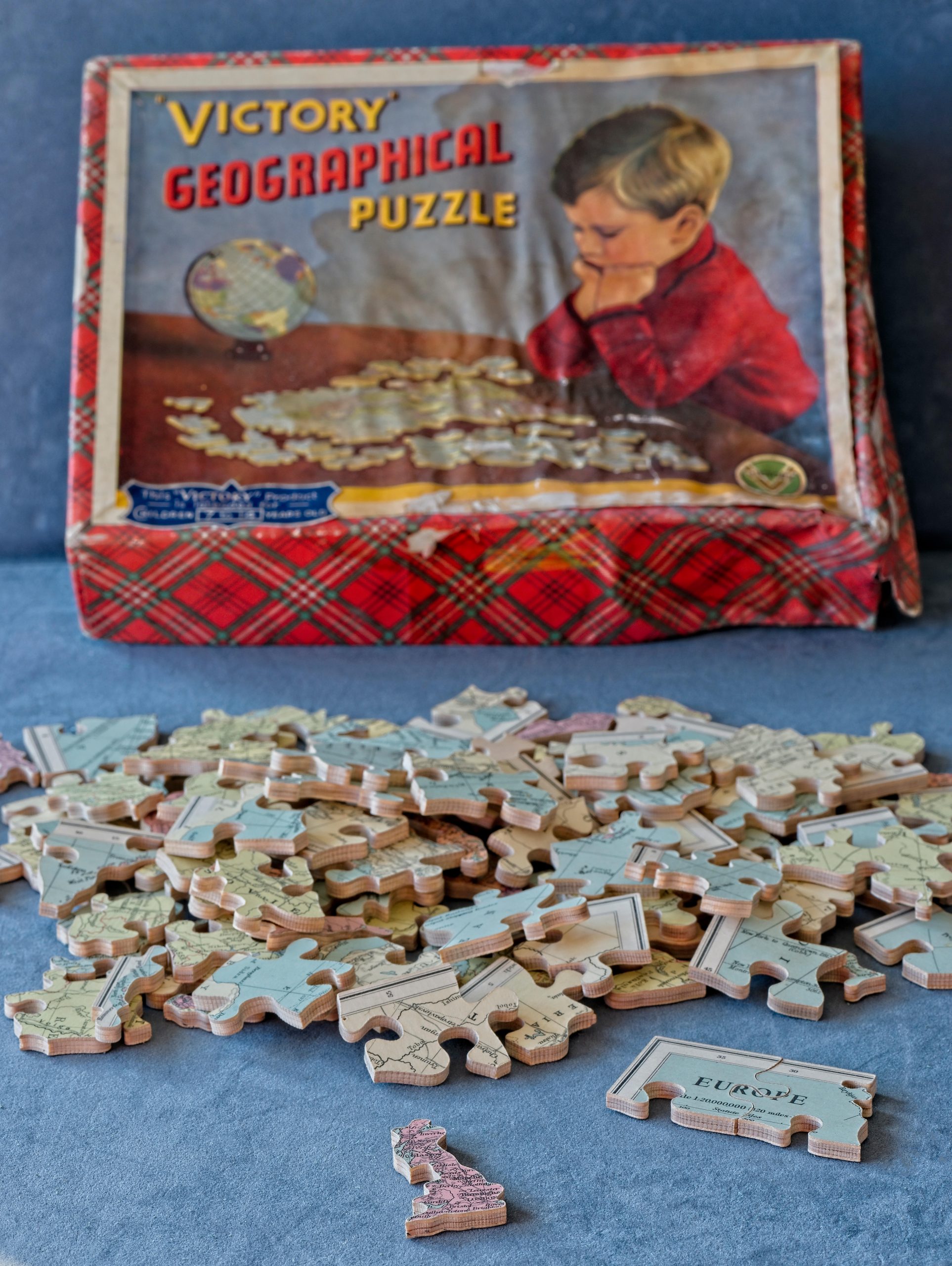

In the 1930s a British manufacturer, Victory puzzles, was responsible for an innovation that came to the rescue of many a puzzler. They began to put their jigsaws in boxes which had the finished image on the front. Enthusiasts regarded this as an egregious form of cheating at first, but the die was cast. It soon became the new normal.

Here in Britain, cardboard puzzles were rather frowned upon, considered shoddy and inferior to the solid wooden ones. It took the outbreak of the Second World War and the secondment of the valuable supplies of plywood for less frivolous purposes for cardboard to be accepted. Even then, the quality of the cardboard deployed was poor, paper shortages not helping, but its use did drive the cost of puzzles down and sustained their popularity during the hostilities.

Jigsaws are enjoying another renaissance and if you are puzzling over one, give a thought to John Spilsbury and a saw.

Curious Questions: How likely are you to be killed by a falling coconut?

Our resident curious questioner Martin Fone poses (and answers) another head scratcher - or should we say, head banger?

Credit: Alamy

Curious questions: Are you really never more than six feet away from a rat?

It's an oft-repeated truisim about rats, but is there any truth in it? Martin Fone, author of 'Fifty Curious Questions',

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Curious Questions: Dirty cash, filthy lucre... but how mucky is our money?

Martin Fone ponders another Curious Question, and comes away thinking that perhaps it's time for us to start money laundering

Credit: apples and oranges Photo by Best Shot Factory/REX/Shutterstock

Curious Questions: Can you actually compare apples and oranges?

It's repeated so often these days that we've come to regard it as a truism, but are apples and oranges

Curious Questions: Why do the British drive on the left?

The rest of Europe drives on the right, so why do the British drive on the left? Martin Fone, author

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.