Curious Questions: What is the world's oldest extant rowing race?

The annual Oxford v Cambridge Boat Race has been a fixture on the sporting calendar of Britain for almost two centuries — but there is a far older example still going, Doggett's Coat and Badge, which boasts an unbroken record of winners for more than three centuries examples. Martin Fone explains.

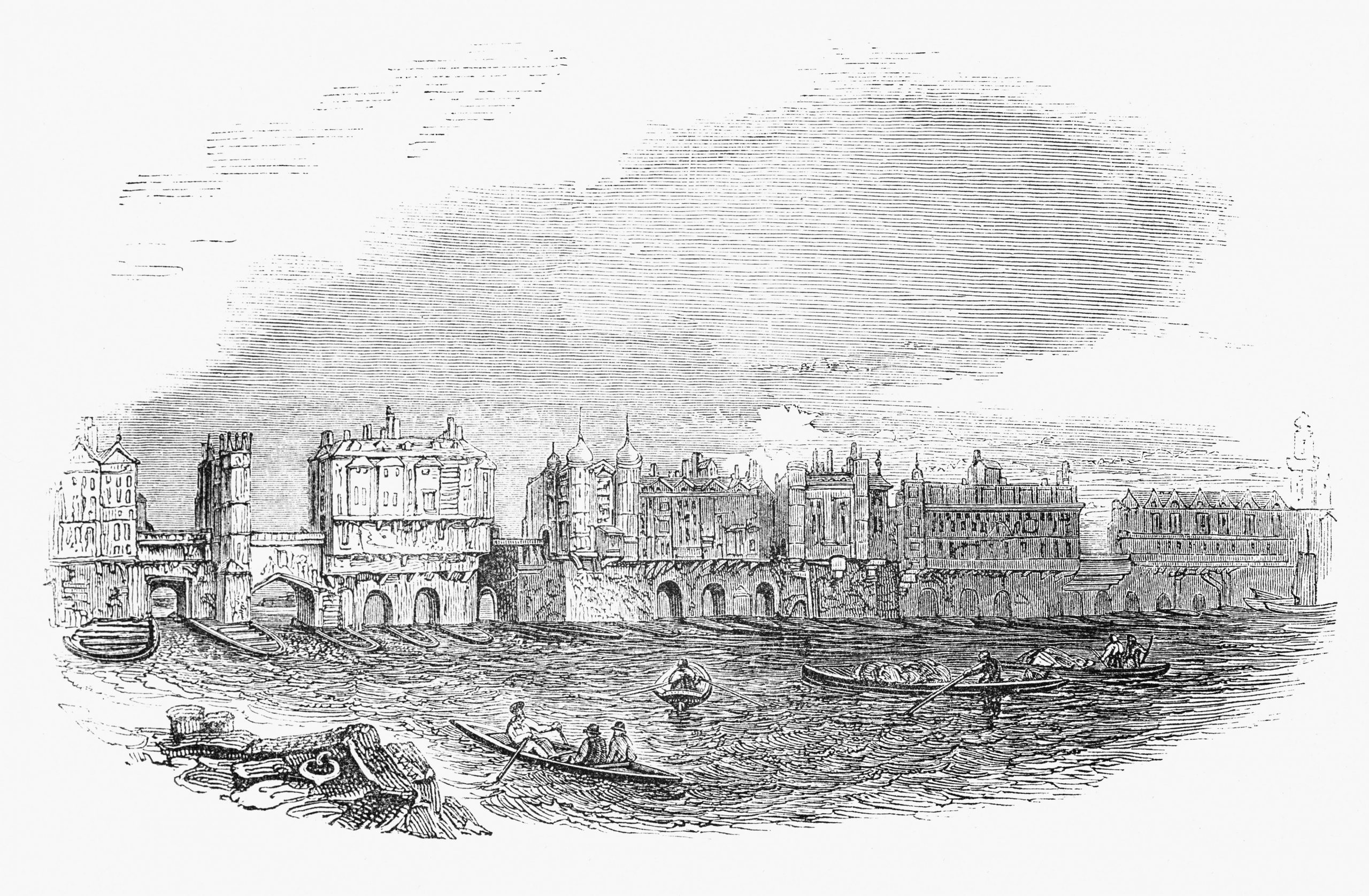

With roads narrow, congested, and poorly maintained and London Bridge the only dry crossing over the Thames until well into the eighteenth century, the easiest way to travel around the capital was by water. Ferries ran at various points along the river, large enough to transport horses and wagons as well as pedestrians. Alternatively, four-passenger wherries could be summoned from the many stairs that led down to Thames. For those wishing to travel along rather than across the river, long ferries ran the length of the river from Chelsea in the west to Greenwich in the east.

Ferry franchises were lucrative and held by the Crown or aristocrats, who leased them out to a waterman. Being a waterman was a skilled occupation requiring a detailed knowledge of the tides and currents of the river as well as the ability to handle a heavy boat in all weathers. It was also extremely competitive, watermen congregating around the stairs, jostling for trade, crying ‘oars, oars, scull, oars, oars’.

John Stow’s A Survey of London (1596) gives an idea of the volume of river traffic and the numbers employed. ‘There pertaineth’, he wrote, ‘to the cities of London, Westminster, and borough of Southwark, above the number, as is supposed, of 2,000 wherries and other small boats, whereby 3,000 poor men, at the least, be set on work and maintained’. London’s population at the time was around 200,000.

The first attempts to impose some order on ferries were made in the 16th century with the passing of a statute in 1514 regulating fares and an Act of Parliament in 1555 establishing the Company of Waterman. A City Guild rather than a Livery Company, it introduced a one-year apprenticeship for passenger-carrying watermen plying their trade between Windsor and Gravesend.

The preamble to an Act of Parliament in 1603 openly criticised watermen stating that people travelling between Windsor and Gravesend ‘have been put to great hazard and danger and the loss of their lives and goods, and many times have perished and been drowned in the said River through the unskilfulness and want of knowledge or experience in the wherrymen and watermen’. Henceforth, watermen carrying passengers had to be at least eighteen years old and to have completed an apprenticeship lasting seven years. They were then entitled to become a freeman of the Company. Fast forward a century and we reach the point where this story truly begins.

Dublin-born Thomas Doggett used his thespian talents to good effect, becoming ‘the leading low comedian of the London stage’ and later an impresario, managing the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, and the Haymarket Theatre. By the time he retired in 1713 he had amassed ‘a fortune sufficient for the rest of his life’.

A staunch Whig, a fervent supporter of the Hanoverian cause, and inspired, it is said, by an encounter with a newly qualified waterman who was the only one prepared to take him across the Thames on a foul night, Doggett placed a placard on London Bridge on July 31, 1715, the eve of the first anniversary of George I’s accession to the British throne. It read ‘there will be given by Mr Doggett an orange colour livery with a badge representing Liberty to be rowed for by six watermen that are out of their time within the year past. They are to row from London Bridge to Chelsea. It will be continued annually on the same day for ever’. The Brunswick Coat and Badge Wager, later known as the Race for Doggett’s Coat and Badge or the Wager, was born.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The following day six watermen chosen by lot, who had completed their seven-year apprenticeship during the previous year, rowed their heavy wherries along the 7,400-metre stretch of river from the site of the Old Swan Tavern by London Bridge to the Swan Inn at Cadogan Pier in Chelsea. Rowing against the tide and taking more than two hours of strenuous effort to complete the course, it was a test of endurance and skill. John Opey of Saviour’s Hill, the winner, received a scarlet coat with a solid silver badge on the sleeve showing a leaping horse and the word ‘Liberty’, as well as a matching cap.

Doggett organised the race each year until his death in 1721. Anxious that the race would not die with him, his Will required his executor, Mr Burt of the Admiralty Office, to establish a Trust to provide annually ad infinitum ‘five pounds for a Badge of Silver representing Liberty, eighteen shillings for a Livery on which the Badge was to be put, a guinea for making up the suit of livery and buttons and appurtenances to it, and 30 shillings to the Clerk of the Watermen’s Hall’.

Burt, though, was reluctant to assume Doggett’s mantle and passed responsibility and the Trust of £300 to the Fishmongers’ Company, who have organised the race since 1722, although from 2019 they have shared the task with the Company of Watermen and Lightermen. It is Britain’s oldest continuously held rowing race, leaving its more famous Thames rival, the Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race, first held in 1829, trailing in its wake.

The winner still receives a coat and badge to Doggett’s design at a ceremony held at Fishmongers’ Hall. To a fanfare of trumpets, they, together with the Clerk to the Company and Bargemaster, are escorted into the Hall by past winners dressed in their coats and badges. The Clerk describes the race in suitably Homeric style, the Prime Warden drinks to the victor’s health, and then the winner is escorted out to the strains of Clarke’s Trumpet Voluntary.

There have been some changes along the way. The race is no longer held on August 1st, the date set according to tides and river conditions. In 1873 the course was reversed, allowing oarsmen to take advantage of the incoming tide. This decision, together with the use of single scull boats, reduced the time to complete the course by three quarters, Bobby Prentice setting the race record of 23 minutes and twenty-two seconds in 1973. Not everyone was enamoured with the change, one contemporary thundering that ‘this deplorable decision to go with the flow obviously marks the start of the subsequent sustained decline in the British national character’.

The Second World War only put a temporary halt on the race. Suspended during hostilities, nine races were held in 1947, one for each of the years that those completing their apprenticeship were unable to enter. This imaginative solution ensured an unbroken roll of winners from 1715, a precedent followed in 2021 when two races were held after the 2020 event fell foul of Covid restrictions.

In 1988, because of the decline in numbers of watermen and apprentices, the qualification criteria were changed to allow competitors to enter within three years of completing their apprenticeship. The first woman to compete, Claire Burran, came third in 1992.

The 308th Doggett Coat and Badge Race, scheduled for July 19th this year, hit choppy waters when the extreme temperatures led to its postponement. It was eventually held on July 28th with George Gilbert of the Poplar Blackwall and District Rowing Club, returning for his final attempt, finishing ahead of first-time entrant Matthew Brookes. The indomitable spirit of the watermen lives on.

Curious Questions: How fast do snowflakes travel?

Martin Fone examines the science behind snow and explores the history of snowfalls in the UK.

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Curious Questions: Should you bring a snowdrop into the house?

Martin Fone delves into Britain's collective passion for Galanthus and looks at the folklore that surrounds it.

Curious Questions: How does a bumblebee fly?

Scientists only discovered the humble pollinator's secret in 2005, says Martin Fone.

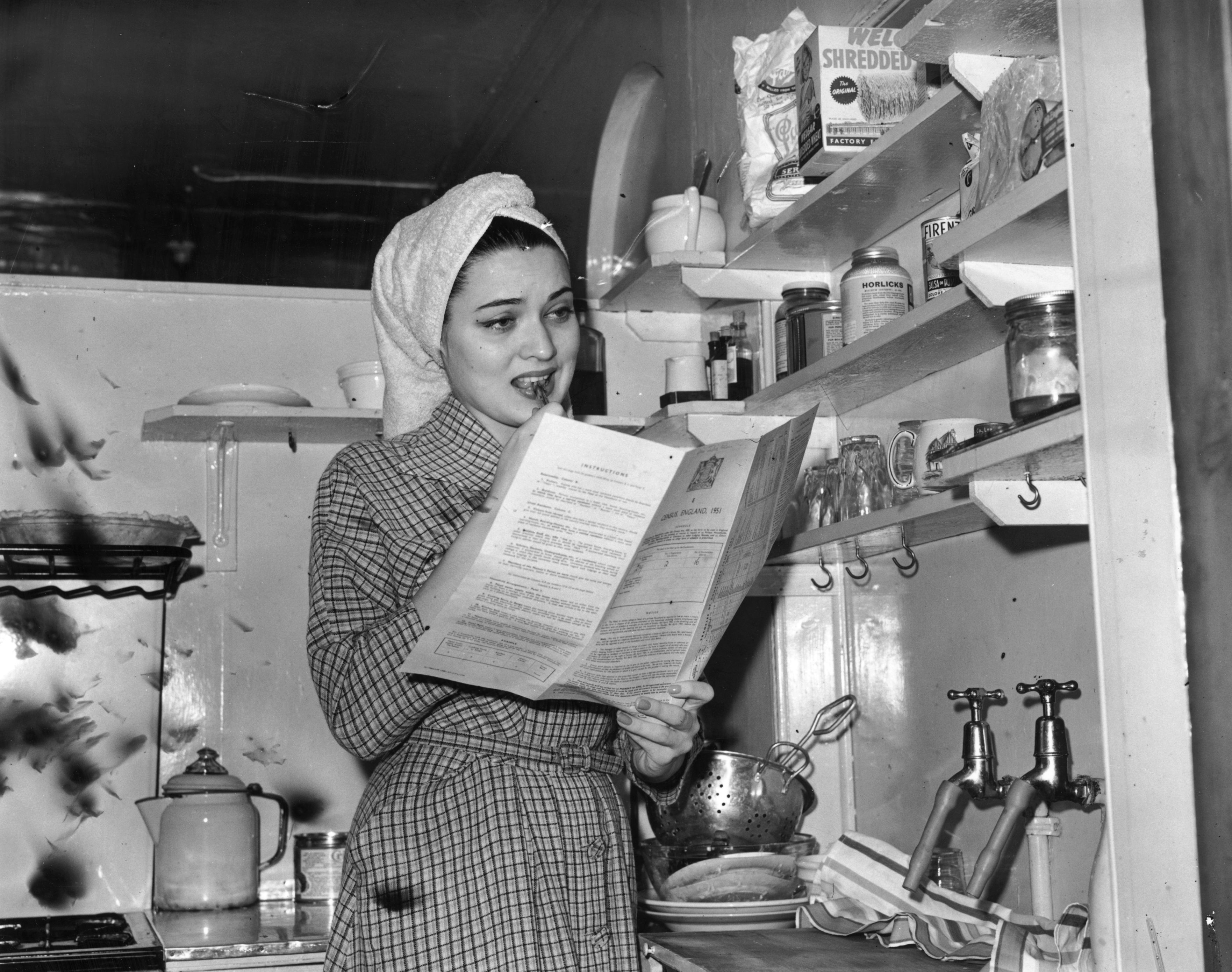

Curious Question: When was the first census held?

As the UK prepares to compile this decade's census, Martin Fone retraces its history.

Curious Questions: When does summer actually start?

You'd think it would be simple. It's anything but, as Martin Fone discovers.

Credit: Getty Images/iStockphoto

Curious Questions: Which came first — the plastic flower pot or the garden centre?

Martin Fone takes a look at the curiously intriguing tale of the evolution of nurseries in Britain.

Curious Questions: Why do Australians call the British 'Poms'?

With England about to take on Australia in The Ashes, Martin Fone ponders the derivation of the Aussies nickname for

Curious Questions: What is a 'doubly-thankful' village — and how did Upper Slaughter become one?

Martin Fone examines the (sadly rare) phenomenon of the parishes who erect memorials not to the fallen, but to those

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.