The life of a 21st century Highland clan chief, from managing 60,000 acres to manning the tills at the gift shop

Their family histories are full of heads on spikes and villages being razed to the ground, but modern Highland clan chiefs face a very different set of problems – including everything from running 60,000-acre estates to manning the tills at the gift shop. Eleanor Doughty spoke to four clan leaders; portrait photographs by Robert Perry and Richard Cannon.

You might be forgiven for imagining that the Scottish clan chief has been lost to history, taking his eagle feathers and his savage warriors with him.

Although the violent battles of the past 1,000 years may now be restricted to television dramas such as Game of Thrones, the eagle feathers remain – tucked in the cap of the clan chiefs, who are still very much around, thank you kindly.

Many of their family histories feature tales of heads on spikes, murderous gangs and arson attacks, but today’s clan chiefs take a rather more civilised approach to life. There’s less fighting and more reuniting – of members of the clan from all over the world. According to the Standing Council of Scottish Chiefs, there are 125 clan chiefs, representing a great breadth of Scottish families, with surnames from Agnew to Wemyss. Within this 125, there are five dukes, 18 earls and 14 baronets, as well as 16 ‘of that Ilk’; they comprise schoolteachers, landowners, barristers and landscape photographers.

The clan system dates back to at least the 12th century, a more troubled time, when battles were fought over dry-stone walls and through slit windows of protective towers dotted around the Highlands and islands.

In 1746, the Battle of Culloden helped to put an end to it all, the Jacobite rebellion crushed by George II’s troops. A tartan ban followed and, later, the Highland Clearances, still a divisive subject, forced thousands of Scots abroad to the New World where, 200 years later, they would begin to launch the modern clan system. Now, the Council of Scottish Clans and Associations has 66 registered international members, with partners in North America most in number.

This is all brought together at its best come summer, during Highland Games season, where, somewhere between the caber toss and the tug-o-war, you might just happen upon the chief, cheering on the members of his international family.

Clan Campbell: The Duke of Argyll

If you visit Inveraray Castle, 60 miles from Glasgow, you might find the 13th Duke of Argyll manning the tills in the gift shop. Torquhil Campbell, 50, head of Clan Campbell, is a down-to-earth chief. His greatest challenge, apart from managing his 60,000-acre estate and bringing up three children (Archie, Marquess of Lorne, Lord Rory and Lady Charlotte) with his wife, Eleanor, is keeping the clan relevant.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

‘My father did a great job of promoting the clan. When Inveraray was ravaged by fire in 1975, he went out to the diaspora and helped to raise the money to put it back together.’

The Duke disregards clan battles of old. ‘Macdonalds and Campbells are old rivals, but, in today’s world, very good friends. Some people do take it quite seriously, but I tend not to – there are several generations under the bridge.’

He officiates at two Highland Games – at Inveraray in July and the Argyllshire Gathering in Oban in August. ‘I walk around with the three eagle feathers in my bonnet, so everyone knows exactly who I am,’ he chuckles.

The Campbell children join in with the marches at the games and love it. ‘It’s great for them to stand back and watch. My sons will do what they think is best when it’s their turn. There’s no written script.’

The Duke has 14 titles, but it’s MacCailein Mòr, his Gaelic title, that means the most.

‘If you look at my inherited titles, they’re given for some purpose. MacCailein Mòr is a blood title. It can’t be taken away – it’s just who I am.’

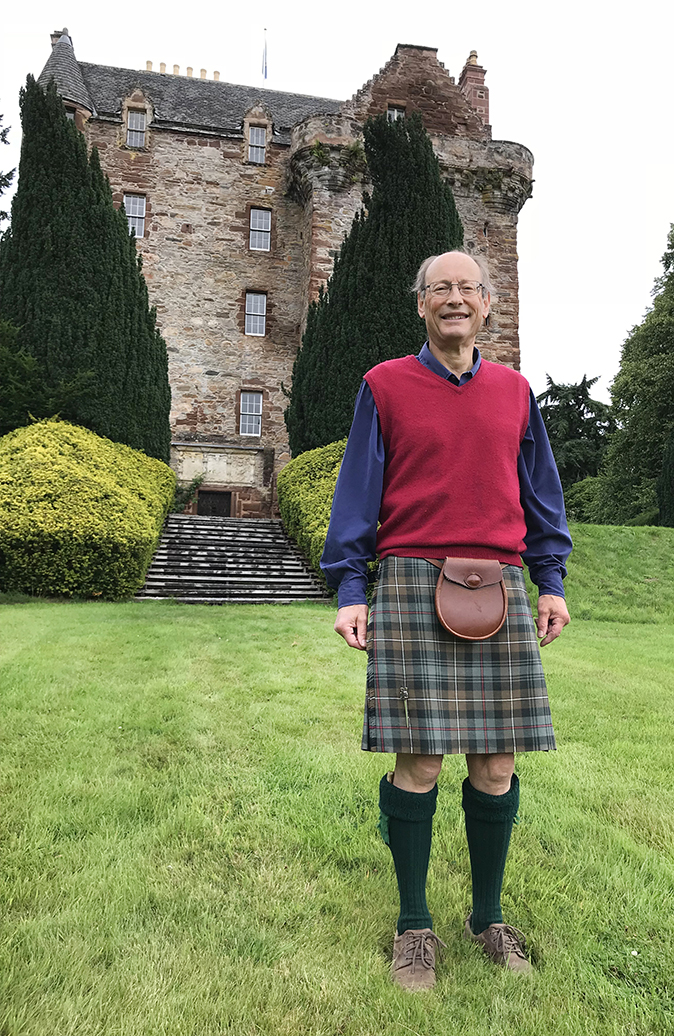

Clan Mackenzie: The Earl of Cromartie

‘I may not have a Highland accent, but cut me in half and I’m all Highland,’ declares John Mackenzie, 70, 5th Earl of Cromartie and chief of Clan Mackenzie. ‘My family has been here 700 years, if not longer,’ he adds from his home at Castle Leod, near Strathpeffer.

Every five years, Castle Leod plays host to an international gathering at which members come from all over the world to the clan seat. ‘It’s probably the best PR this country is ever going to have,’ points out Lord Cromartie.

‘The clan system sells Scotland – it sells the concept that clans are beyond things like race, creed or politics.’

At the turn of the century, Lord Cromartie set about healing some old wounds. ‘At the international gathering in 2000, we made a formal peace with Clan Donald. Godfrey Macdonald [the Lord Macdonald, high chief of Clan Donald] and I met with swords drawn, literally, our pipers all playing conflicting tunes. We had a peace witnessed and signed and we went off to have a fantastic ceilidh after.’

He hopes that he’ll be able to do the same with Clan MacLeod, ‘whom the Mackenzies, one of my direct ancestors, I have to admit, civilised pretty brutally in the 16th century’.

It doesn’t do to be a wallflower, as clan chief. ‘You have to have a fairly robust outward persona,’ says Lord Cromartie.

‘It’s much more difficult if you’re very shy, which I was when I started, but you grow with it. I no longer feel that it’s an imposition, but that it’s something that I can give to other people. It’s like giving something back.’

Clan MacLeod: Hugh MacLeod

‘It doesn’t feel a big responsibility to be clan chief because it’s essentially a symbolic role,’ acknowledges producer and director Hugh MacLeod, 45, who inherited the chiefdom of Clan MacLeod in 2007.

Mr MacLeod divides his time between London and the 42,000-acre Dunvegan Castle estate on the Isle of Skye, the clan seat for the past 800 years, proving that the family motto ‘Hold fast’ certainly works.

He smiles grimly when explaining the Battle of the Spoiled Dyke of 1578, in which a party of Macdonalds came over from Uist to Trumpan, about 20 miles from Dunvegan, on a Sunday: ‘When the MacLeods were in church, they barricaded the doors and burnt everyone alive.’

A teenage girl squeezed out and brought help; in the subsequent battle, a dyke collapsed on the bodies of the Macdonalds. It was in retaliation to an event the year before, when ‘the MacLeods went to the Isle of Eigg, a Macdonald stronghold, took the people into a cave and lit a fire outside’.

Today, MacLeod’s rival clan chief, Lord Macdonald, poses more of a culinary threat: ‘His wife [Claire Macdonald] is a very good cook, who, along with her husband, established Kinloch Lodge, a hotel and restaurant on Skye.’

Mr MacLeod has quite a reputation to live up to. His great-grandmother Dame Flora MacLeod was one of the most famous clan chiefs of the 20th century. ‘My father described her as the first professional clan chief. She was passionate about reawakening the sense of shared ancestry with the diaspora around the New World.’

When his father, John, inherited the title, however, international travel was less of a priority than the restoration of Dunvegan Castle, which ‘was teetering on the brink of financial collapse. Dame Flora was not a businesswoman’.

Mr MacLeod’s approach to keeping the clan alive takes a more modern approach. ‘You can have more impact posting material on a Facebook page without the need to travel. That’s the method that I’ve adopted.’

Clan Macdonald: Ranald Macdonald senior and Ranald Macdonald junior

In one branch of the Macdonald family, three generations of men have the same name: Ranald Macdonald. Ranald senior, 84, is the Captain of Clanranald; his son, Ranald, 54, runs the Boisdale restaurant chain in London and his son, Ranald, 23, is a musician.

Ranald senior became clan chief in 1956. ‘We did clan stuff all the time during my childhood, always going to piping competitions,’ explains Ranald junior, who grew up in London, but feels Scottish.

‘It’s a relationship that you continually rethink, to a degree,’ he reflects of the clan. ‘If I get the opportunity, I’ll bang on about it. If you don’t bang on about it, who’s going to?’

Today, their clan lands – which included Moidart in the West Highlands; the main Clanranald stronghold of Castle Tioram is now a romantic ruin – are much depleted. ‘My brother has a house in South Uist, an old Clanranald house, and I’m looking to buy a place – I can’t decide between the Outer Hebrides and the west coast.’

He’s realistic about it, however. ‘It’s not as if we evolved to this land – we came to it, otherwise we’d be able to cope with midges.’

His father, who has now been clan chief for 62 years, feels a deep sense of pride about his position: ‘It’s a bit trite, but I’ve been able to put something into our heritage.’

Ranald senior inherited the captaincy from Angus Macdonald, a distant relation. ‘My father died when I was very young and he always said to my mother that, when the war came, I’d be the next chief. I knew that there was something important coming, even if I didn’t understand it.’

The clan still matters today. ‘Tens of thousands of people are clamouring to identify with something. It’s not important in the traffic jam, but it’s very important in the bigger picture.’

Country Life's Scotland special issue is out on 22 August – find out more about what's in the magazine.

Credit: Gleneagles Hotel, Scotland

The Gleneagles Hotel review: Heaven in the Highlands

The Gleneagles Hotel review: Heaven in the Highlands

Credit: Skibo Castle

Highland Retreats review: Proof that shooting lodges that aren’t all freezing monstrosities

A new book by Mary Miers, Country Life's fine arts and books editor, had Adam Nicolson gripped.

Spectacular Scottish castles and estates for sale

A look at the finest castles, country houses and estates for sale in Scotland today.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.