In Focus: Handel's Messiah, the Christmas music that was created for Easter

Handel's Messiah

At this time of year, Handel's Messiah is everywhere. In London alone, it will be given its 567th live outing since 1872 at the Royal Albert Hall. Yet its composer envisaged it as a piece for Easter. Only the first part of the oratorio is concerned with the birth of Jesus Christ, with the other sections touching on His death, Resurrection and Ascension. It was the relative dearth of sacred music relating to the yuletide season that led to its adoption as a Christmas standard by the early 19th century.

George Frideric Handel (1685–1759), who was German born and became a naturalised British citizen in 1727, wrote 25 oratorios, effectively introducing the form of the music to England by combining aspects of his adopted country’s masque and anthemic choral traditions with those of Italian opera and Italian and German oratorio. Messiah is by far the most famous of all these works, yet the circumstances leading up to its creation involved controversy.

Born in Halle, Germany, the composer had first visited England in 1711; his opera Rinaldo was performed in London that year. It was received with such enthusiasm that he took up residency the following year, his music gaining royal and noble patronage. Staging operas in London at this time was ruinously expensive, however, requiring the hiring of pricey Italian singers and, by the late 1720s, the comic operas of the likes of John Gay (The Beggar’s Opera) were drawing bigger audiences than Handel’s more serious works.

Handel, however, disdained comic opera and turned to the oratorio because it could be performed by less demanding English singers and did not require lavish sets and costumes. The problem was that firm dividing lines were maintained between the performance of secular and religious material. When, in 1732, Handel tried to stage his first oratorio, Esther, at the King’s Theatre (later Her Majesty’s) in Haymarket, the main London venue for Italian opera, there was an outcry about a Biblical story being told by ‘common mummers’.

Handel ran the risk of further accusations of blasphemy with Messiah, the lyrics of which, written by Charles Jennens, were straight from the scriptures. It took Handel only 24 days to put those words to music with a 259- page score; some later claimed he was working under divine inspiration.

The premiere of Messiah took place in Ireland, in the Great Music Hall in Dublin, in April 1742, partly as an attempt to avert another angry response in the capital. Even there, Jonathan Swift, then Dean of St Patrick’s Cathedral, denounced it and tried to prevent the cathedral’s singers from taking part. Although it received rave reviews, it was given only a muted reception when first performed in London the following year. It was not until it was successfully performed in its entirety at a concert to raise funds for the still unfinished Foundling Hospital, of which Handel was a supporter, in 1750, that it started to gain acceptance with London audiences.

For its Dublin performance, Handel had been able to call upon about 30 cathedral singers and a similar-sized orchestra. Over the years, the numbers involved became increasingly gargantuan. At a festival in Westminster Abbey marking the 25th anniversary of the composer’s death in 1784, there was a 300-strong choir and a comparable-sized orchestra.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The Handel Festivals staged at the Crystal Palace from the 1850s drew on 4,000 singers and an orchestra of 500 musicians. This must have been a stupendous spectacle: that mighty ensemble belting out the ‘Hallelujah’ chorus as an audience of 20,000 rose to their feet, a traditional nod to the occasion when, legend has it, George II sprang from his seat (possibly to stretch his legs, rather than in ecstasy) at the London premiere.

Later, there was an inevitable trend back towards scaled-down productions, attempting to reproduce the sort of intimate, authentic sound that Handel might have recognised. However, the most popular English choral work of all time has remained a favourite with amateur choirs and orchestras who, what- ever they may lack in finish, sometimes come closer to the oratorio’s message of faith, hope and the glory of God than is found in more polished, professional performances.

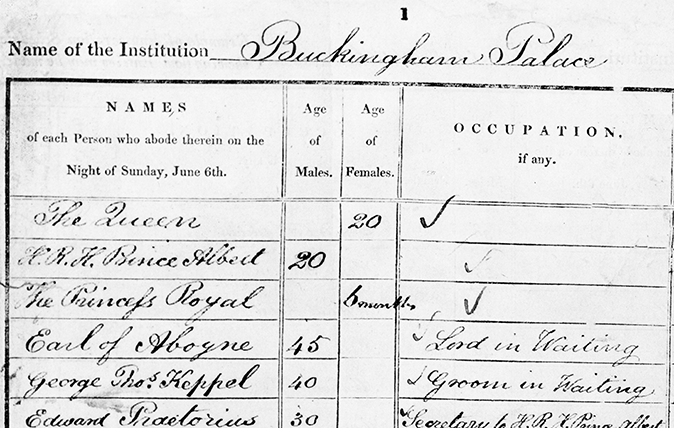

Seven fascinating things we just learned about the Census

Ysenda Maxtone Graham is riveted by the facts and figures revealed in this engaging history of the Census.

The London life or the country life: Who's right?

Ysenda Maxtone Graham discusses the age old debate which divides the nation in two.

Curious Questions: Were summer holidays better in the good old days?

Quieter roads, no stressing about dodgy wi-fi and the comforting pong of the cooler opening — were things really better in

Credit: The Beaumont

Curious Questions: Why are we suckers for comfort food?

Shepherd’s pie, steak-and-kidney pudding, treacle sponge... these staples on the national menu are like old friends, lifting spirits in times

Jack Watkins has written on conservation and Nature for The Independent, The Guardian and The Daily Telegraph. He also writes about lost London, history, ghosts — and on early rock 'n' roll, soul and the neglected art of crooning for various music magazines