Driving Land Rovers blindfolded, cricket in the corridors and sword-fights in suits of armour: The unusual games of the country house

Big houses and grand spaces leave lots of potential for some strange games. Melanie Cable-Alexander investigates.

Driving a Land Rover blindfolded might not be everyone’s idea of fun, but, according to the Duchess of Fife, it can be a hoot. The idea, she explains, is to place two pairs of people in two vehicles and to encourage them to navigate a series of cones set in separate lanes, with one person in each couple at the steering wheel wearing a pair of blacked-out swimming goggles and the other issuing directions. ‘It’s hilarious when a husband-and-wife team is involved,’ she adds.

The Duchess and her husband are nothing if not adventurous when it comes to entertainment at their home, Kinnaird Castle in Angus — particularly at Christmas, when the weather is inclement and the castle, by virtue of its sheer size, comes into its own, with games (albeit not the aforementioned Land Rover driving) being transferred from outside to indoors.

You can tell that the corridors at Kinnaird are one big playground from the moment you walk into the main entrance hall, which has an air-hockey table right in the middle of it. Tractors, scooters and rollerblades (‘easier on stone than grass’) are given free rein in the long stone downstairs corridors and the top-floor corridor is devoted to crazy golf and bowls (‘the carpet is green, so it made sense’). The old kitchen is the trampoline room and the former staff dining room is for yoga.

Best of all is the dedicated (and unheated) games room, created from a two-storey library and a second drawing room that was never rebuilt after a fire 100 years ago. The space houses, among other things, a ‘near enough life-size’ badminton court and a full-length cricket pitch with a strong net ‘to prevent broken windows’. It’s a room that Ben Cowell, director-general of Historic Houses, recalls vividly from his visit to the castle a few years ago. ‘It was cavernous, with the full height of the room reaching up to the rafters as the ceiling had not been replaced,’ he remembers. ‘The Duke explained that they were quite happy for the space to remain as it was because the family played games there.’

It may seem surprising for such grand spaces to be set aside for light-hearted recreation, but it is not unusual, as art historian Kate Retford, professor of History of Art at Birkbeck, University of London, points out in her essay A family home and not… a museum: living with the country-house art collection. ‘Scholarly interest has generally focused on the country-house art collection as a site of display,’ she writes. ‘We less often think of them as elements of a backdrop to the inhabitants reading, sewing, playing music, conversing’ — and, of course, playing games.

Prof Retford refers to a painting by Elizabeth Chute of the lower gallery at the National Trust’s The Vyne in Hampshire, dating from 1877. The gallery in question had been converted into a place in which the then owner’s many children could play. Prof Retford writes that in the picture, ‘marble statues, busts and paintings jostle with a rocking horse, a horse on wheels, a net strung up for battledore (or shuttlecock), a train track with a couple of carriages falling off the end and a large variety of tools’.

It all sounds not dissimilar to sights met at Kinnaird, suggesting that these big country houses make natural playgrounds, especially their corridors. This point was made by another Duchess, the late Deborah (‘Debo’) Cavendish, who described children roller-skating along the corridors of Chatsworth, Derbyshire, in her book about the house, adding that ‘on a wet day you can walk for hours, be entertained and keep dry’ (she did also say that, less conveniently, ‘a bag put down can be lost for months’ and ‘it is a terrible place to train a puppy’).

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Etymologically, the word corridor derives in part from the Latin currere, meaning to run, which is a trifle irritating for children when that’s what they are mostly told not to do in them. One of the first times the word appeared in the English language was when the 1st Duchess of Marlborough questioned Sir John Vanbrugh’s design for her new home Blenheim Palace and his unusual distribution of rooms in 1716. The architect explained: ‘The word Corridoor, Madam, is foreign, and signifies in plain English, no more than a passage.’ Later on, the Duchess’s descendant, Sir Winston Churchill, used these same Vanbrugh-designed corridors and rooms to invent a game called The English and the French, which, according to Antonia Kearney, Blenheim’s social historian, ‘resembled a rugby scrum and had only two rules: one, that Churchill was always the General and two, there was no promotion. No prizes for guessing why!’

Churchill’s game is a classic example of H. G. Wells’s belief that country-house corridors could give ‘the men of tomorrow […] new strength’ and ‘build up a framework of spacious and inspiring ideas in them’, as well as ‘keeping children happy for days’. So inspired was he by life at Easton Glebe, Essex, where he was staying as a tenant of the Countess of Warwick, that he wrote Floor Games, in which he penned these words, in 1911. Two years later, he followed it with Little Wars, which set rules for playing with toy soldiers.

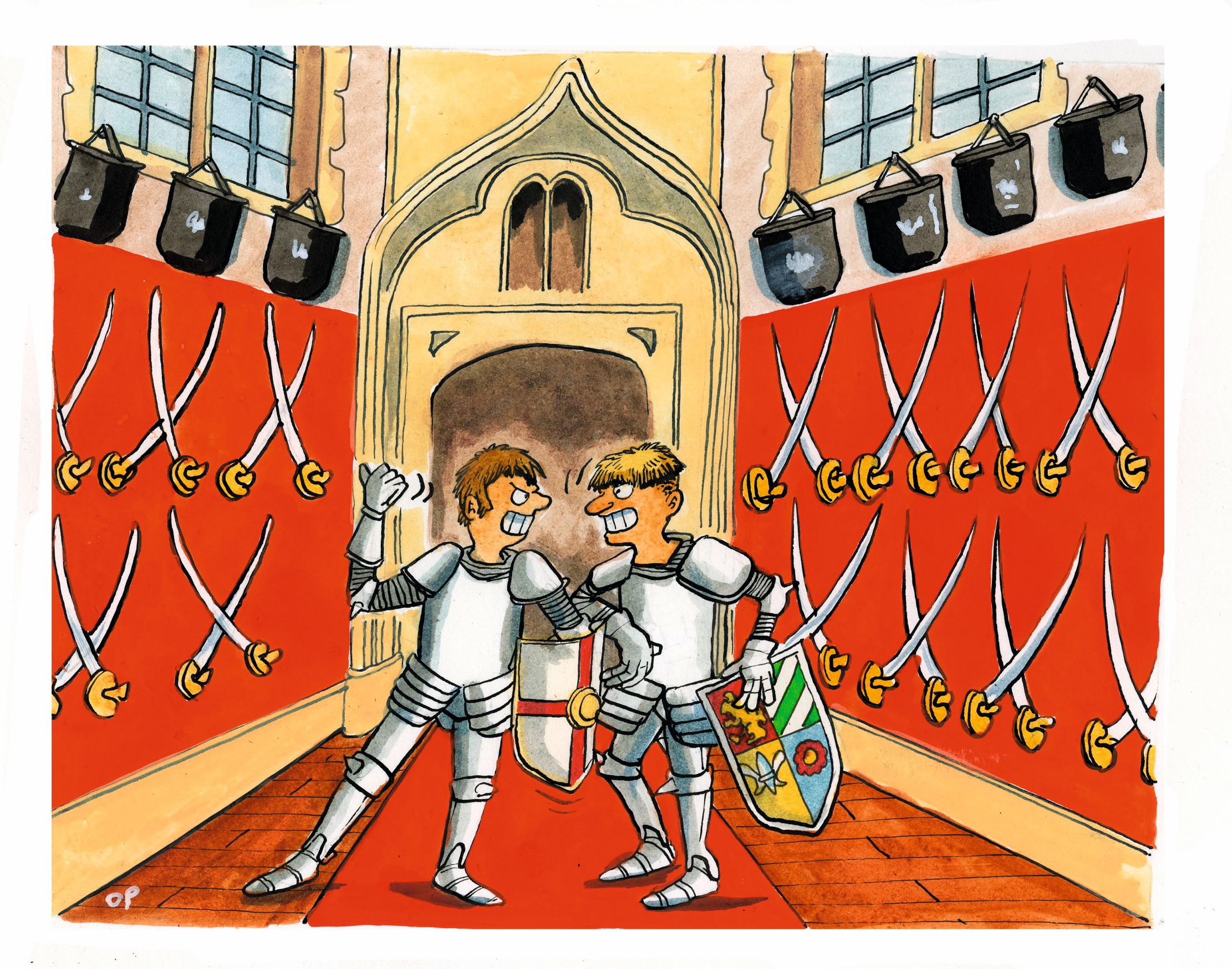

Cartoonist Oliver Preston recalls playing real-life soldiers as a child with swords grabbed from the walls at his friend’s house, Arbury Hall in Warwickshire (‘fortunately, they were blunt’) and participating in a version of corridor football at Eton in Berkshire. ‘My house had three floors of narrow, wiggly corridors with fire doors breaking up the passageways. These made excellent goals.’ It was another school, Charterhouse, then in London, that played a version of football in its corridors, which later led to the creation of the offside rule.

Mr Preston also remembers a cartoon in Polo magazine of a child riding the family great Dane down a long corridor, swinging a mallet. Country Life’s own Annie Tempest has illustrated an equally unexpected sight — that of a butler riding a Sinclair C5 (Sir Clive Sinclair’s doomed recumbent electric vehicle) along an endless corridor. It was inspired by C5s being ‘a bit of a joke at the time’ and her life at Broughton Hall, her family home in North Yorkshire, now a smart wellness sanctuary run by her brother Roger.

The cartoon may have been semi-fictional, but it is not unknown for motorised vehicles to whizz down country-house corridors, as the Duke of Richmond reveals. ‘My grandfather always said he rode his motorcycle in Gordon Castle quite a lot,’ he reminisces. The Duke’s own family home, Goodwood House in West Sussex, doesn’t have many corridors as the rooms open onto each other — although he did once hold Goodwood’s legendary annual cricket match indoors in the ballroom ‘because the weather was so awful, which probably wasn’t the best idea’. At Christmas, everyone plays a version of hide-and-seek across the ground floor in a game devised by the Duke’s grandmother.

Spooky games are often a feature of country-house corridors, particularly as the nights draw in. The Countess of Carnarvon makes much of ghostly corridor creepings in her blog about Highclere Castle, Hampshire, and Viscount Hereford says that his father, the 18th Viscount, ‘always encouraged his house guests to embark on a ghost hunt after dinner’ down the corridors of Hampton Court Castle in Herefordshire. Growing up at the castle perhaps allowed him to have ‘fond’ rather than petrifying childhood memories of visiting the Drummond family at Megginch Castle in Perthshire, where his friend’s father Humphrey Drummond ‘would encourage us to head down through a secret door to a winding staircase to the dungeon, where a skeleton attached to fishing nylons and chains would leap to life, terrifying us’.

Fishing lines were used for a different purpose by Miss Tempest’s father, who wanted to put a stop to corridor creeping of another kind. ‘To prevent us misbehaving when we were in our teens, Dad would put fishing-line trip-wires by the boys’ bedrooms,’ she recalls. Had that happened to the zoologist Desmond Morris, he would have been far less amused, for it was during a spot of corridor creeping when playing sardines at a country-house party in 1949 that he met his future wife. He declared the episode as proof of love at first sight — but the story may have been very different had the pair been sitting next to each other in a Land Rover on the Duchess of Fife’s instructions.

Melanie Cable-Alexander is a journalist and editor

The £30 million Dorset estate that comes with a 200-year-old mansion, a cricket ground, a nature reserve and an entire village

The Bridehead Estate in Dorset has come up for sale — and it's quite an astonishing opportunity. Penny Churchill takes a

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.