Curious Questions: Who do we say that cats have nine lives?

Martin Fone set off to investigate the origins of the saying that cats have nine lives. In the process he discovered something less supernatural, but no less incredible.

‘A cat has nine lives’, the proverb goes, ‘for three he plays, for three he strays and for the last three he stays’. In Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet (Act 3:1), Mercutio goads Tybalt, whom he has already called a rat-catcher, by demanding: ‘Good king of cats, nothing but one of your nine lives, that I mean to make bold withal, and, as you shall use me hereafter, dry beat the rest of the eight’. Thomas Fuller claims in Gnomologia: Adagies and Proverbs (1732) that ‘a cat has nine lives, and a woman has nine cat’s lives’. Cats enjoying nine lives is well established in English folklore, but why?

One theory is that this association originated in ancient Egypt where cats were revered as divine creatures with psychic or supernatural powers. Atum-Ra, a sun god, who assumed a feline form when he visited the underworld, gave life to four gods who, in turn, produced another four, known collectively as the Ennead. The Egyptians regarded Atum-Ra, the cat god, as the embodiment of nine lives in one form.

Elsewhere the number nine is regarded as being imbued with special significance, the trinity of trinities and the final numeral. In China it is thought to be a lucky number, while numerologists associate it with forgiveness, compassion, and success. The belief that cats have nine lives is not universal, though. In some Spanish-speaking countries they have seven while in Turkish and Arabic folklore they are short-changed still further, with just six.

"One in New York City fell from a window on the thirty-second floor of a building... After two days at an animal hospital, it was well enough to return home"

In truth, even the most ardent ailurophile will concede that they only have one life, but is there some trait in a cat’s behaviour that leads to the belief that they are death-defying?

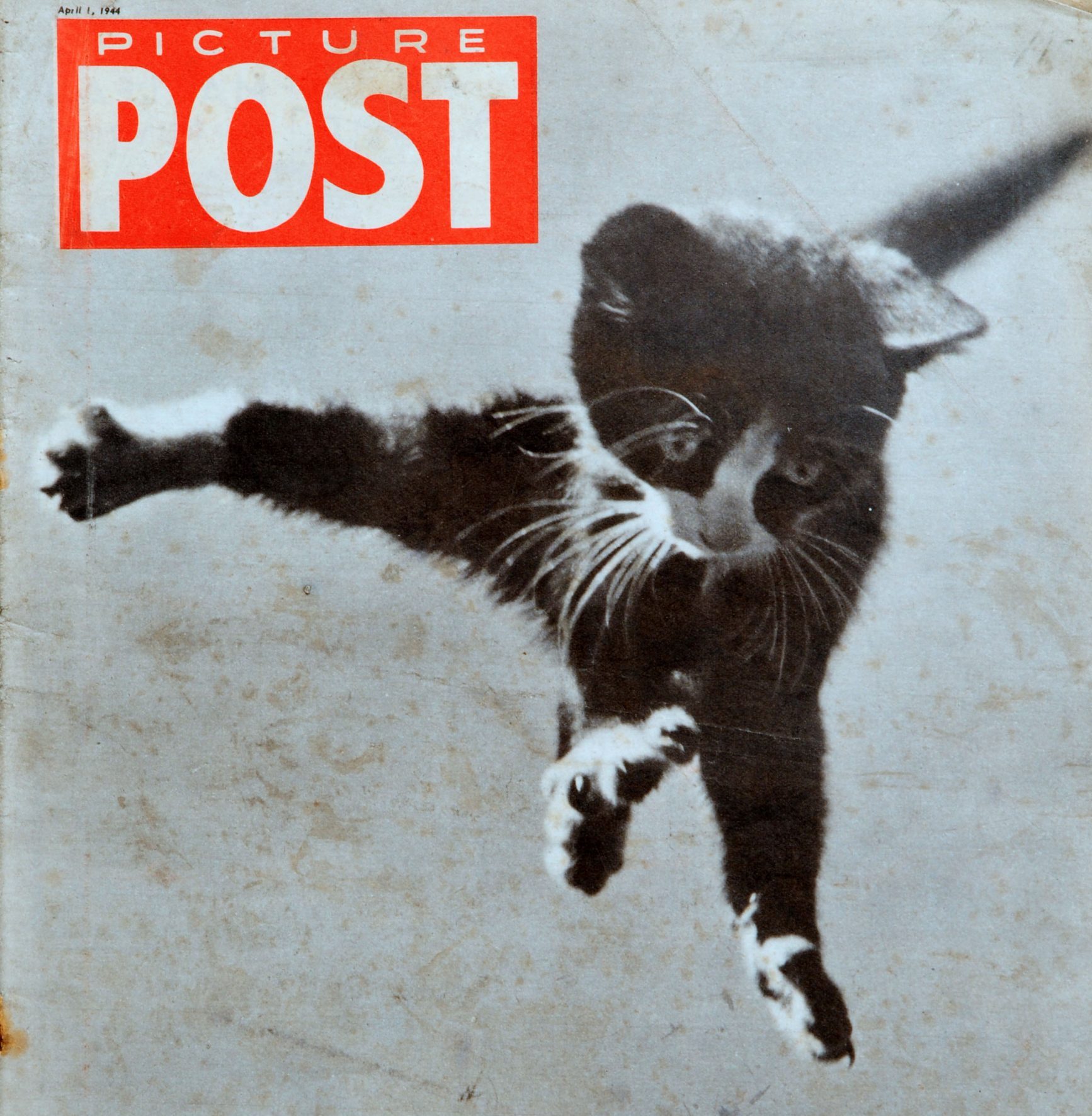

Well, yes. They have a remarkable propensity to fall from height and land on their feet, apparently unharmed, something that has not always worked in their favour.

The Kattenstoet is held in Ypres in Belgium on the second Sunday of every May, a parade commemorating the custom, dating from the Middle Ages, of throwing cats from the seventy-metre-high belfry tower of the Cloth Hall down to the town square below. Again, the origin of this curious ritual is lost in the mists of time, but cats were used to protect the wool stored there from the predations of vermin over winter. Once spring arrived, the wool was sold, they were redundant, and the ungrateful merchants simply tossed them out of the windows.

And it seems that the cats survived. In 1817, after the defenestration of a live cat, the town’s keeper remarked that ‘in spite of the height of the fall, the animal ran off quickly that it might never be caught again in a similar ceremony’, as well it might. You’ll be glad to hear that proved to be the last time a real cat was used; puppets are used in the modern ceremony.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

https://youtu.be/WCfldjHXmOE?t=597

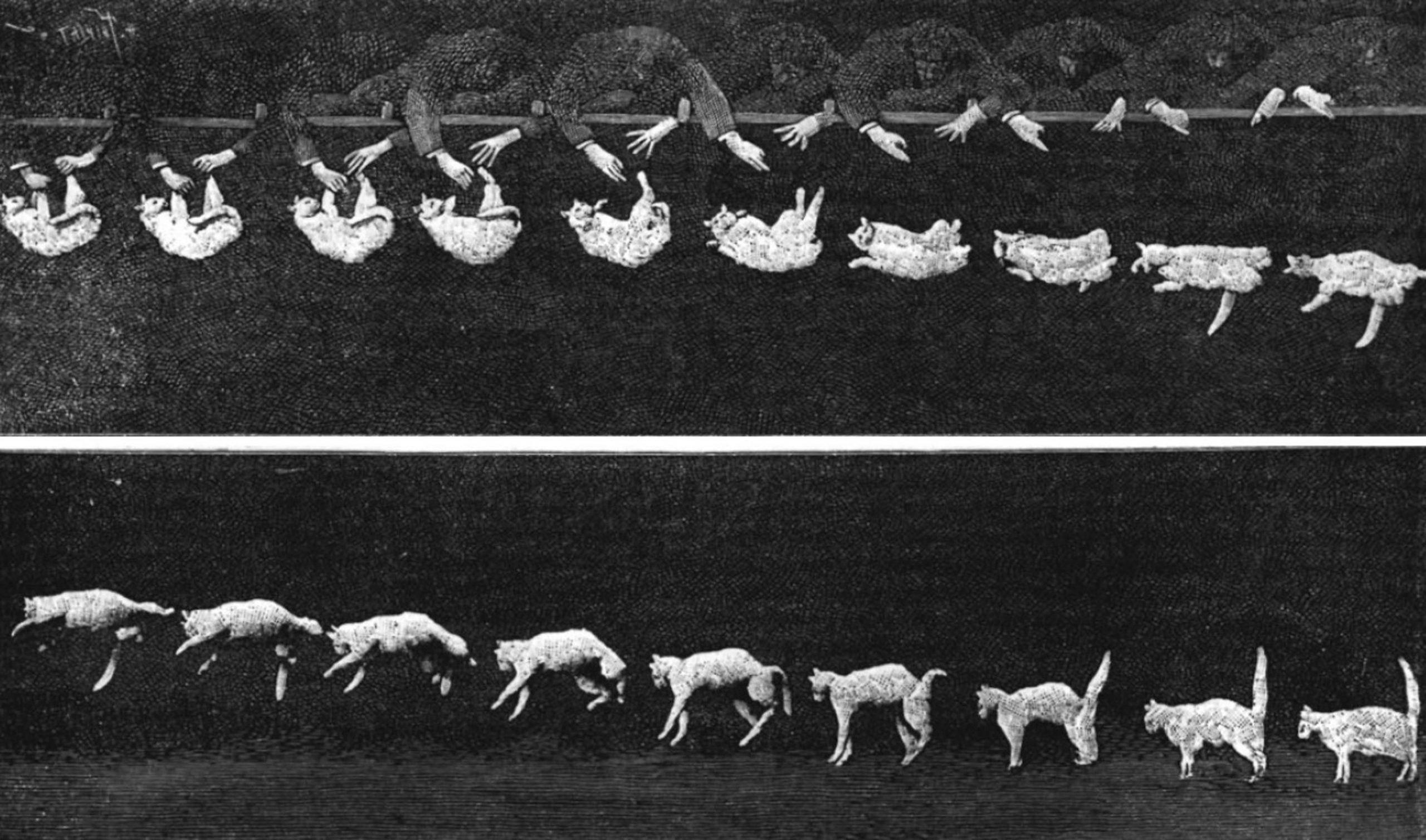

Exactly how a cat was able to survive a fall from height was discovered in 1894, thanks to the pioneering use of a chronophotographic camera by French physiologist, Etienne-Jules Marey. He used the camera, which had a shutter speed of sixty images per second, to capture what happened when he held his cat upside down and dropped it. What he saw was it twisting itself, and manoeuvring its head, back, legs, and tail into an upright position to soften the impact when it hit terra firma.

What Marey had captured was his cat using its highly advanced vestibular system located in its inner ear which controls balance and orientation. It triggers the righting reflex, allowing it to assess quickly which way is up and to adjust its body in mid-flight. Kittens begin to demonstrate their ability to right themselves after just three weeks and by seven weeks their righting reflex is fully functional.

The cat, though, has other built-in advantages. As tree-dwelling hunters, they evolved highly muscular, angular legs, ideal for climbing, jumping, and absorbing the impact of landing, and a skeletal system, which included thirty vertebrae and no collar bone, that made their backbone incredibly flexible, reducing the risk of damage to their bones when they fall. In comparison to their surface area, their bodyweight is low, a factor which helps to reduce the rate at which they descend, giving extra time for the righting reflex to kick in.

A cat’s ability to survive a prodigious fall is well attested. One in New York City fell from a window on the thirty-second floor of a building, sustaining a chipped tooth and a collapsed lung. After two days at an animal hospital, it was well enough to return home. More astonishingly, a cat fell 46 storeys without sustaining injury, earning itself a rather dubious world record, although pedants point out that a canopy partially broke its fall.

You won't be surprised to hear, in the age of the smartphone, that similar falls — albeit not from quite such a height — have been caught on camera. A cat ; screams of horror can be heard from the crowd, but the brave moggie lands safely on a grass verge and scooted off unharmed.

https://youtu.be/v55PcFYeZ2c?t=29

These astonishing feats of survival led to speculation as to whether cats were especially adapted to survive long falls. Grist to that mill was provided by some research published the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association in 1987 which looked at 132 cats that had fallen from buildings and been brought to the New York Animal Medical Centre. The study revealed that on average they had fallen the equivalent of 5.5 storeys, the furthest was 32, and although two-thirds required some form of medical intervention, and half of those would have died without treatment, their survival rate was around 90%.

Perhaps most intriguingly of all, the researchers found that after a certain point, falling further actually helps the cat’s chances of survival. While initially the injuries per cat increased depending on how high the fall was, there was a tipping point at a fall of around seven storeys. After that, the number of injuries actually decreased.

"Cats have a relatively low terminal velocity of 60 mph, which they reach around the five-storey mark... After that they have time to adopt a more relaxed body state, using it rather like a parachute"

The researchers suggested an explanation. When cats begin to fall, they tense up and arch their backs and rely on their physiological advantages to survive. This proves an admirable strategy for short distance falls, but less so for falls which are longer but not long enough for the cat to reach its terminal velocity, the point where its speed while falling remains constant.

Cats have a relatively low terminal velocity of 60 mph, around half that of humans, which they reach in a fall at around the five-storey mark. Up to that point injuries increase in severity, but then they have time to adopt a more relaxed body state, using it rather like a parachute, and so minimise their injuries.

The flaw in their research, though, was that the sample was skewed significantly towards cats that had initially, if not ultimately, survived their falls. After all, owners would not take their cats to a veterinary surgery if they had been killed outright. Further doubts were cast on the findings by a study of 119 cats that had fallen at least four storeys, published in October 2004 in the Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. One of its key conclusions was that ‘falls from the seventh or higher storeys are associated with more severe injuries and with a higher incidence of thoracic trauma’.

Regardless, it’s still quite incredible that survival is even a vague possibility from such huge falls; cats are naturally adapted to survive relatively unscathed the type of falls which, to the human eye, would seem to be life-threatening. No wonder that as they became domesticated, it led to the belief that they led charmed or several lives. Sadly, though, they are just like us: mortal.

Credit: Getty Images/EyeEm

Curious Questions: How did cats come to be man's second-best friend? (Or best, depending on who you ask)

In the last few weeks, Martin Fone has been taking a look at how dogs were first domesticated and the

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Curious Questions: Why do cats have whiskers?

Martin Fone investigates the all-important role of feline whiskers—including how they contribute to enhancing the species' beauty.

Credit: Karen Parker via Alamy

Curious Questions: Why isn't there a Crufts for Cats?

Charles Cruft was a salesman-turned-showman who created the world's biggest dog show — yet Cruft himself owned a cat. So

Credit: Alamy

In praise of cats, our 'lithe, scrupulously clean and interesting companions'

Most people identify either as a dog person or a cat person, and Country Life's default focus is usually canine.

The nine greatest cats in literature, from Macavity to the Cat Who Walked By Himself

Macavity, Macavity, there’s no one like Macavity – apart from the other eight on this list, as picked out by Emma

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.