Want to keep chickens? Here are 22 unusual breeds that'll give you a bustling coop — and maybe some pink eggs for breakfast

Lockdown has made the idea of keeping hens — and harvesting their eggs — even more appealing, but the populations of a surprising number of delightful native breeds are dwindling. Kate Green takes a look at some unusual but rewarding poultry to consider.

As pandemic panic-buying hit the country this spring, the unassuming egg suddenly became under-the-counter contraband in village shops. Soon, lucky chicken owners were swapping half a dozen fresh eggs for a bag of pasta, a couple of loo rolls or last week’s Country Life.

As lockdown set in, together with an innate reluctance to return to the office, the idea of a few hens tranquilly clucking in the background has made staying at home even more beguiling. But what to get? You could go for one of the usual breeds such as the Rhode Island Red, but there are far more interesting birds out there.

Peter Hayford, an octogenarian poultry farmer near Totnes who started keeping chickens with his mother during the Second World War, has been inundated with requests in recent months. But as president of the Rare Poultry Society (RPS), he would like to see more people keeping native fowl than the ubiquitous faster-maturing, commercial hybrids.

He keeps some 20 different breeds and says that, if forced to choose one, it would be the Dorking — ‘a lovely, traditional chicken that has a nice shape’. He also likes the Scots Dumpy — ‘a great little chicken, not flighty, but, of course, they’ve got such short legs they can’t get off the ground’ — and would love to see renewed interest in the handsome North Holland Blue, which was a popular dual-purpose fowl in the post-war days of necessity.

‘Natives tend to be more trouble to keep, but they don’t wear out so quickly,’ Mr Hayford observes. ‘Hens have a natural seed tray within them — when it runs out, they stop laying; with hybrids, that’s after four or five years, with pure-breds, after about eight years.’

Professor Philippe Wilson, the Rare Breeds Survival Trust’s newly appointed head of conservation, says he ‘became obsessed with breeds that need rescuing from a young age’. He started out keeping Derbyshire Redcaps, which slept up trees at night, and he now practises what he preaches by supporting the little-known Modern Langshan, of which there are only about 40 in the world. ‘They’re magnificent, tall birds, great in a curry and they lay wonderful pinkish eggs,’ he says.

Find out more at www.rbst.org.uk, www.rarepoultrysociety.com, www.poultryclub.org, while there are individual breed-club websites for more popular chickens.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Derbyshire Redcap

Rare dual-purpose birds whose USP is the impressive rose comb, which is key to success in showing and should not hang over the eyes. Redcaps, which nearly died out in the 1960s, are a particularly pure strain with little out-crossing.

Dorking

Named for the Surrey town, this breed has been around since Roman times. It was popular in the London markets until it was superseded by the Sussex. Revived by enthusiasts in the 1960s, Dorkings come in red, silver-grey, cuckoo, dark and white shades and have a distinctive fifth toe.

Indian Game

Originally the Cornish Game (although it’s a faux pas to call it that now), having being developed in the West Country from Asian strains imported into Falmouth and Plymouth. Its purpose switched in the 19th century from cock-fighting to table-bird breeding sire. Comes in shades of Dark, Jubilee and Double Laced Blue and may lay tinted eggs.

Ixworth

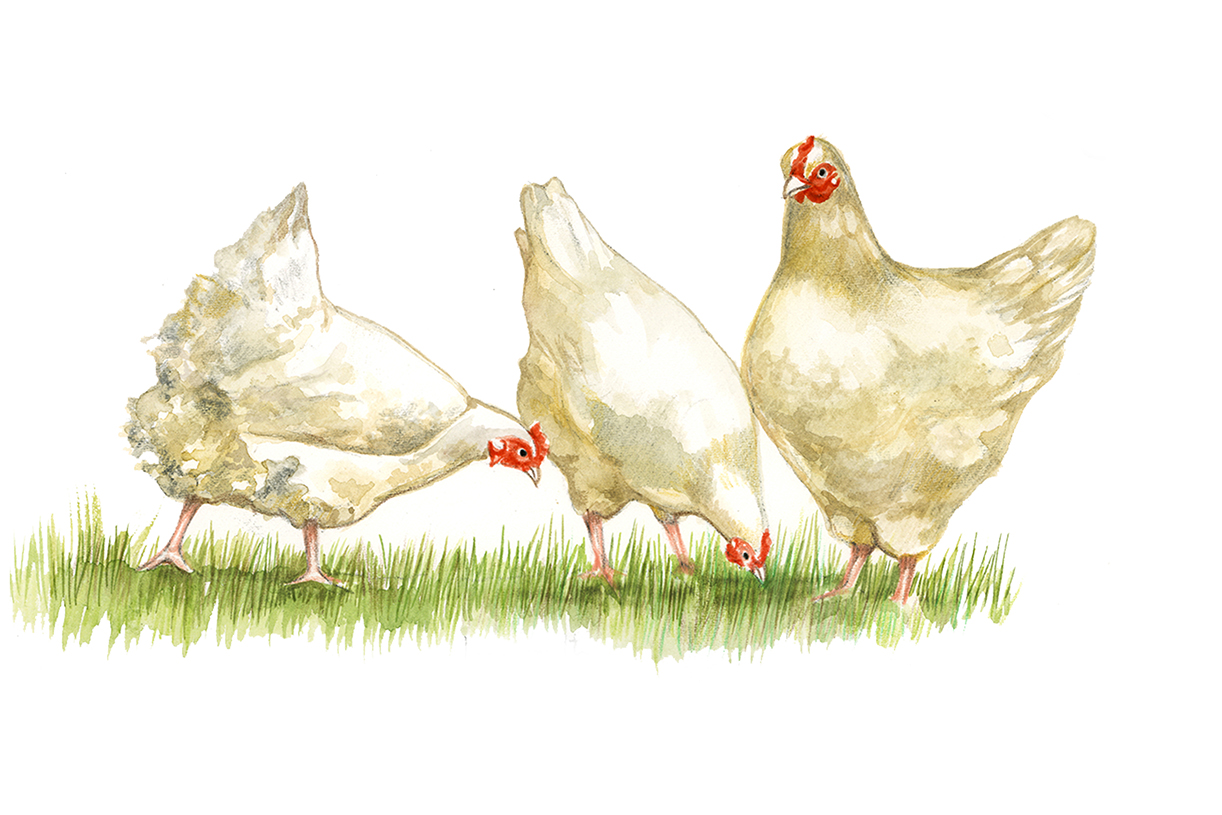

Created by Reginald Appleyard (who also produced some lovely ducks) in 1931 and named after his Suffolk birthplace, the snowy-white Ixworth is a busy forager and likes to live free range. Revived by conservationists in the 1970s, it’s said to have the best meat of any pure-bred.

Lincolnshire Buff

Once prolific on Lincolnshire farms for the London markets, the now rare Lincolnshire Buff was quickly — and controversially — outclassed by the Buff Orpington, whose creator denied there was any connection between the two. The Lincolnshire recovery in the 1980s owes much to exhibitor Brian Sands; a breed society was formed in 1995.

Norfolk Grey

In about 1910, Fred Myhill of Norwich crossed Silver Birchen Game with Duck-wing Leghorns and called the result Black Maria after a German military shell. When Myhill returned from the First World War, he had to start again and decided to call them Norfolk Greys. They’re now rare — at one stage in the 1970s there were only four birds — but are friendly and potentially good layers of pale-brown eggs.

Old English Game

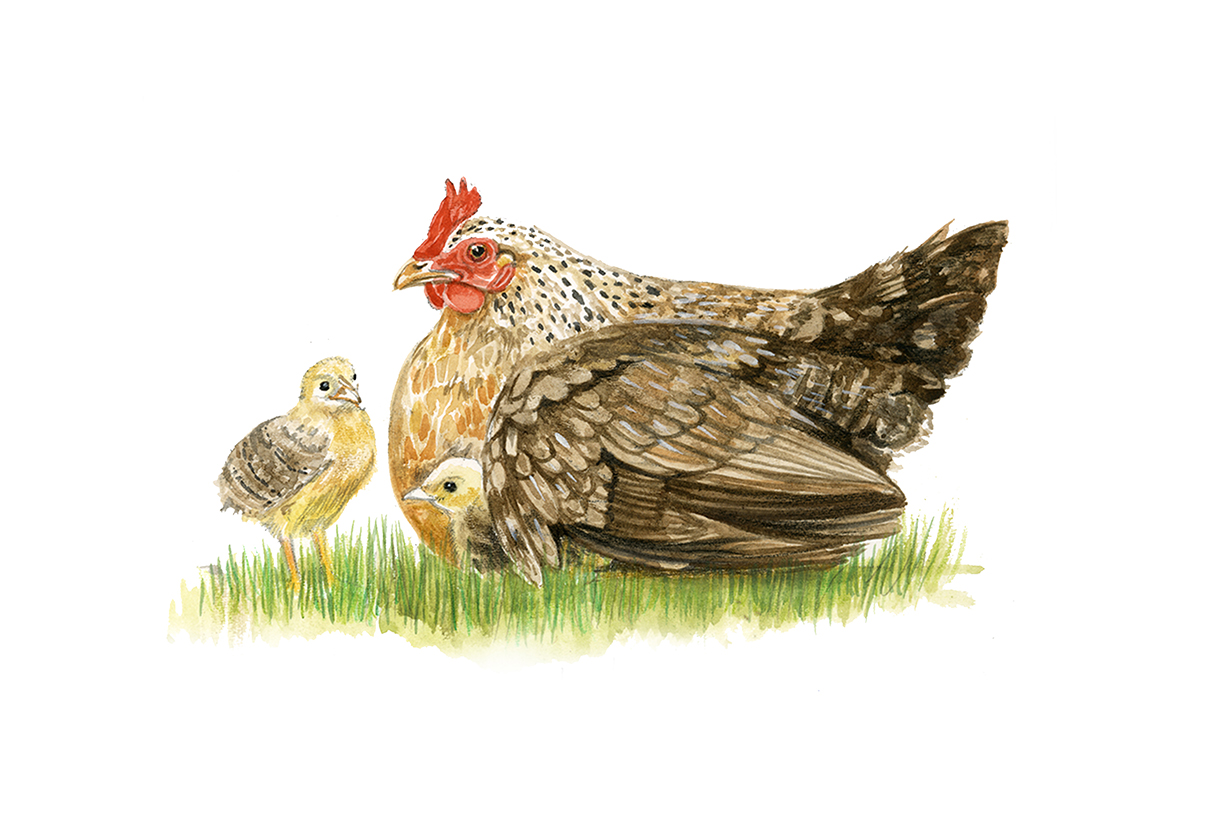

Hardy birds once bred for cock-fighting, so possibly not the best bet for novice keepers — they can be fiercely independent. In the 1930s, disagreements over the bird’s development led to the formation of two clubs, the Carlisle and the Oxford. The Carlisle has a broader back; the Oxford is slimmer and nearer the original. They lay modest numbers of small, tinted eggs and, unusually, cockerels sometimes take over rearing the brood.

Old English Pheasant Fowl

A pleasingly old-fashioned-looking bird that was recovered by dedicated breeders, who searched farms in the Yorkshire Dales for the centuries-old types developed from the Gold Spangled Yorkshire Pheasant and the Lancashire Mooney Fowl. They’re hardy, flighty and don’t like to be penned in, but the hens lay well (white eggs) and the cockerels produce delicious breast meat.

Orpington

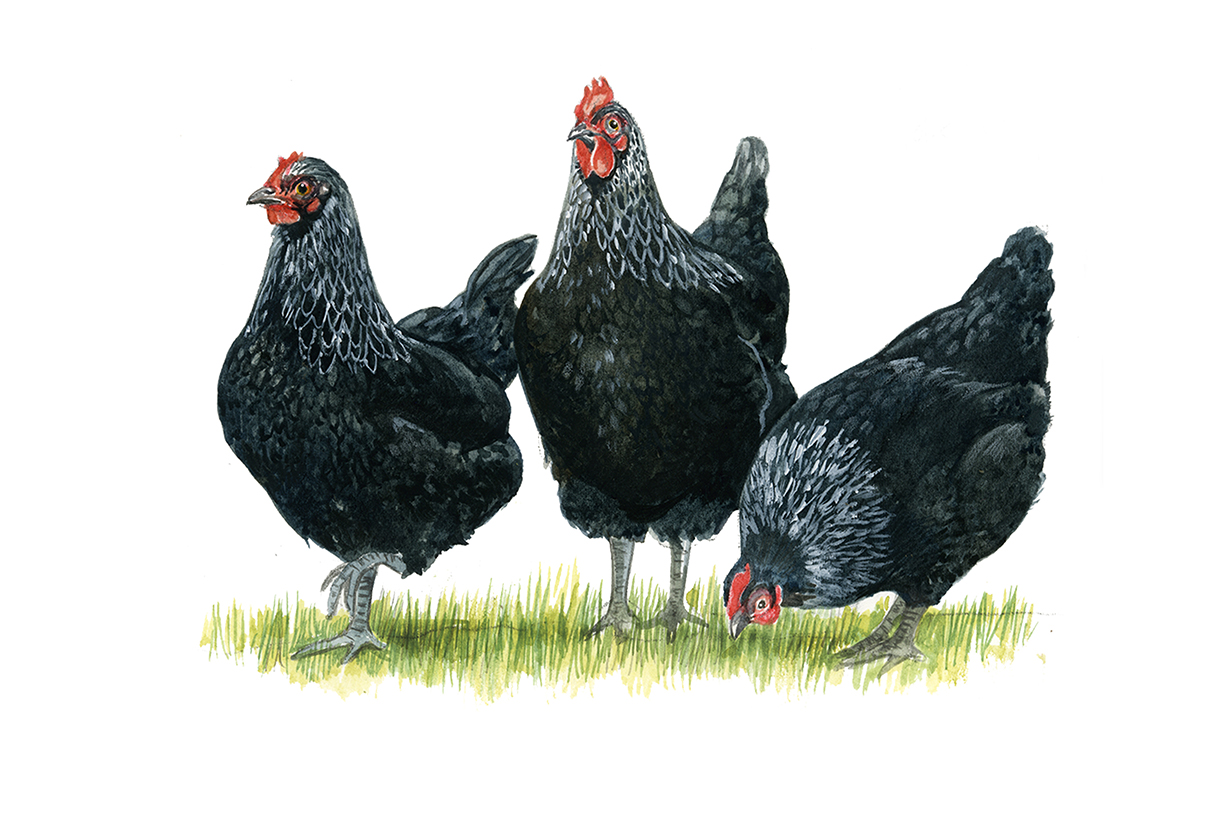

Magnificent, matronly fowl bred in 1886 to public acclaim by William Cook, a coachman from the eponymous Kent town, at a time when poultry trends were moving from the exotic to the productive and practical — the Black Orpington was bred to hide city dirt. In 1894, to even greater excitement, the Buff Orpington arrived. Cook’s cuddly chickens also come in white and lavender plus a rare speckled variety, the Jubilee, created in 1897 in honour of Queen Victoria.

Scots Dumpy

An ancient breed — and noisy (they legendarily warned the Picts of the approaching Roman army) — they were rescued from near extinction in 1977 when a descendant of Lady Violet Carnegie, who had moved to Kenya with a flock of Scots Dumpies as her dowry, agreed to send 12 eggs back to Britain. The charming, waddling Scottish chicken — also known as a ‘creepie’, ‘bakie’ or ‘daidie’ — bears a similar dwarf gene to Dexter cattle. It makes less mess in the garden than other breeds and comes in black, white or an attractive cuckoo pattern.

Scots Grey

Another ancient Scottish breed that, in contrast to the Dumpy, is of haughty, upright stance with long legs. It has barred plumage — it’s also known as Shepherd’s Plaid. Once ubiquitous, it’s now rare, but deserves to be more popular — the hens lay well and aren’t prone to broodiness. The cockerels are imposing and can get feisty.

Suffolk Chequer

A new breed — it was only recognised by the Poultry Club of Great Britain in 2013 — this pretty bantam with barred plumage looks like a mini version of the American Plymouth Rock from which it’s descended. In 1994, Suffolk-based geneticist Trevor Martin crossed a miniature Barred Rock male with a brown laying hen, the idea being to create a fowl displaying the attractive barred plumage of the Plymouth Rock, but with a longer tail.

Sussex

A breed that is frequently recommended to novice keepers, the original Sussex — also the Surrey or Kent fowl — was exhibited at the first ever poultry show, in 1845, and has one of the oldest breed clubs, formed in 1903. It comes in eight standard colours: the Light Sussex — white, with a dark-grey collar and tail feathers — is the most popular and probably the most prolific layer, but the Speckled is arguably the most attractive. In 1936, Robert Whittington created the Coronation, a lavender version of the Light, to celebrate the crowning that never was of Edward VIII.

Welbar

This richly coloured West Country breed was started by one H. Humphreys of Eastwrey, south Devon, in the 1940s, using the Plymouth Rock and Welsummer. It produces beautiful dark-brown eggs.

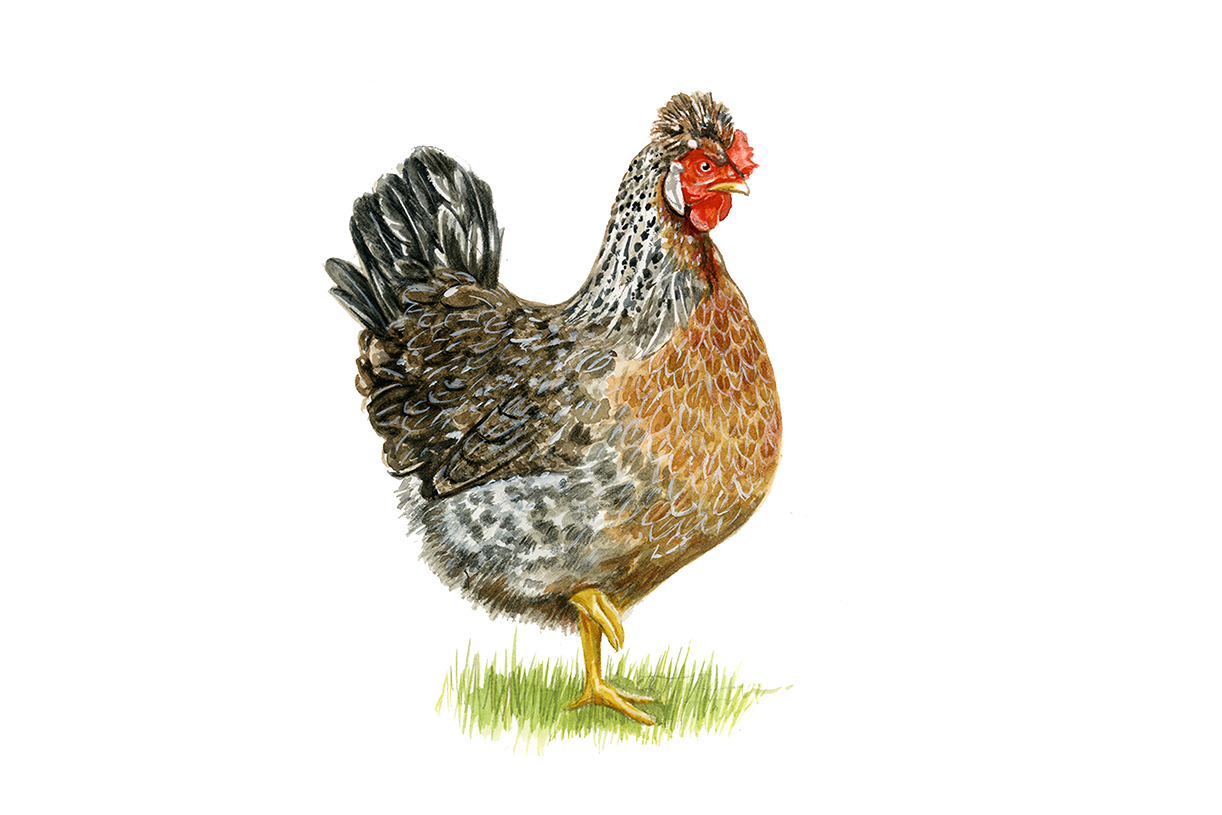

Bluebelle

Of all the hybrids, this is surely the most dazzling, with an unusual grey-blue plumage — it’s surely only a matter of time before it’s patented as a paint colour. A large, placid chicken, which should be a prolific layer of brown eggs, it was developed by Meadow-sweet Poultry in Co Durham, which holds the trademark, by crossing the Rhode Island Red with the Maran.

Cream Legbar

When, in the 1930s, geneticist Michael Pease of Cambridge University’s poultry department attempted to improve the Gold Legbar by crossing it with a Leghorn, he ended up with some ‘interesting cream chicks’.

He crossed these with blue-egg-laying Araucanas belonging to Prof Reginald Punnett, who created the first auto-sexing birds (when the chicks can be sexed at a day old). However, there was little demand for exotic shell shades in the austere 1970s and the birds would have died out, but for the intervention of the Wernlas Collection of rare breeds — plus renewed enthusiasm for blue/green/olive eggs. The Cotswold Legbar, pivot of the original Clarence Court egg business, is another offshoot.

Marsh Daisy

The delightfully named bird suffers from a poor hatching rate and nearly died out in the 1970s, when west Somerset farmer and RPS president Ralph White discovered a stock locally. The breed was started in 1880 in Lancashire by John Wright of Marshside, using strains of Old English Game, Cinnamon Malay, Black Hamburgh, White Leghorn and Sicilian Buttercup (hence the green legs), but was not seen in public until 1919. It deserves a wider audience, as it has a gentle nature, is hardy and is a pretty good layer of tinted eggs.

Modern or Croad Langshan

In 1872, a Maj Croad imported Langshan fowl from northern China (Langshan means wolf hill in Chinese). Because it looked suspiciously like a Black Cochin, the breed society elected to promote the Modern Langshan, a taller fowl with tighter plumage; Maj Croad’s niece disagreed and formed the rival Croad Langshan club, which survives to this day, unlike the original — that club didn’t last the Second World War. The birds lay pinky-brown eggs, the colour described as that of a dewy, unwashed plum.

North Holland Blue

This extremely rare breed, originally from the Netherlands and once commercially valuable, exemplifies British enthusiasm for conserving unusual breeds; it owes its existence here to one Les Miles, who kept them in his back garden in Enfield, Hertfordshire. It only comes in one colour, cuckoo, and is so named because, from a distance, it looks blue. It lays light-brown eggs and is good to eat.

Rosecomb

The first known reference to this attractive bantam, which looks as if it’s stepped out of a Dutch Old Master, was in 1483, when John Buckton, proprietor of the Angel Inn, Grantham, was recorded as having a flock. They found favour among the landowning gentry when Richard III, who had rooms at the inn, took a fancy to them. Classified as a true bantam (no bigger-size chicken counterpart), it makes a delightful pet; the most common shade is a glossy black.

Rumpless Game

This sad-looking bantam would, admittedly, be a really niche interest, especially as the egg yield is low. It has no backside or, more precisely, no caudal appendage or ‘parson’s nose’, with the result that it moves with a forward-thrusting gait. There are rumpless Belgian and Japanese breeds, as well as a rumpless Araucana, and it’s thought to have been produced by genetic accident, in a cross with the Old English Game.

Sebright

Another genuine bantam, the Sebright was created some 200 years ago by Sir John Sebright, a politician, landowner and agriculturalist, who wanted a showy bird with gold or silver laced plumage — the silver strain came via a white Rosecomb cock from London Zoo. Sebrights aren’t easy to breed — the gene pool is small — and they’re not prolific layers, but they’re charmingly ornamental in a mixed flock.

Kate is the author of 10 books and has worked as an equestrian reporter at four Olympic Games. She has returned to the area of her birth, west Somerset, to be near her favourite place, Exmoor. She lives with her Jack Russell terrier Checkers.