How Anna Sewell wrote Black Beauty, the 'hymn to a horse' whose influence on animals is still felt today

A hymn to the horse, a comment on slavery, an ode to rural Norfolk: Anna Sewell’s enduringly popular novel is all this and more 200 years after its author’s birth, explains James Clarke.

In 2017, a rare edition of Black Beauty went up for auction in Norfolk, in aid of the local Redwings Horse Sanctuary. The fact that the title is still cherished enough to merit its listing proved a reminder of how powerful and moving Anna Sewell’s novel remains. Initially published in the run up to Christmas 1877, by Norwich-based publisher Jarrold and Co, the childhood favourite has never been out of print.

Told from the point of view of Black Beauty (Michael Morpurgo adopted the same story-telling device in War Horse), the book takes the reader on the horse’s life journey in both town and country. Despite the various locations in which the novel unfolds, including London, where Black Beauty works as a cab horse, the novel is a clear tribute to the author’s connection to Norfolk. ‘Norfolk was the county of her birth, death and family heritage,’ explains Prof Adrienne E. Gavin, author of a biography of Sewell entitled Dark Horse.

Born 200 years ago, on March 30, 1820, in Great Yarmouth on the east Norfolk coast, the part of the county that would become essential to the spirit of Sewell’s iconic novel was the Bure Valley, a landscape that mixes marshland and crop fields, through which the River Bure laces its way towards the Broads.

Sewell’s family went on to live in London and then Brighton, but she returned to Norfolk in the last years of her life to write Black Beauty. The author would often visit her relations in East Anglia, too, so the landscape formed a powerful thread through her life.

The expansive East Anglian countryside has long hummed with human activity and it’s this ebb and flow between people, landscape and animals that is so memorably rendered in the pages of Black Beauty.

The Bure Valley can be walked quite easily today, between Aylsham and Wroxham, but Sewell had injured her ankle as a child and it never fully healed. As a result, she would often get around using a pony and trap and it was at Dudwick House in Norfolk that she learnt to ride, during a visit to her uncle and aunt; her grandparents lived nearby at Dudwick Farm. Sewell would go on to corral her memories of these places in the service of her novel.

The author disliked towns and cities and Black Beauty captures the unease that found a voice during the Industrial Revolution, as people became concerned about the loss of country ways and tradition. There is a realism to the novel that reflects Sewell’s knowledge and memory of both country and equestrian life, with the plot moving across rural and urban settings and situations that both test and nurture the horse. It is the novel’s first half, however, where her Norfolk soul sings out.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The village of Buxton in the middle of the Bure Valley was a place of inspiration, as was Old Catton, where she spent the last decade of her life. She and her parents moved into the Georgian White House on Spixworth Road in 1867, having returned to Norfolk to help and support her brother Philip, the widowed father of seven children. It was here that she wrote Black Beauty; she also kept bees.

At the time, Old Catton was a village on the edge of Norwich. Philip owned land nearby, at Clare House, where he kept a horse named Black Bess. Used to pull his carriage up and down the Spixworth Road, Bess was kept in a barn that is understood to have informed Sewell’s image of Black Beauty’s stable. The barn still stands and is now the venue for the Sewell Barn Theatre.

Indeed, for anyone who wants to make a pilgrimage, a memorial to Sewell stands at the junction of Constitution Hill and St Clement’s Hill in Norwich. Ada Sewell (her cousin) erected it in 1917 — it origin-ally served as a horse trough and, today, it brims with flowers.

In part, Black Beauty is a novel that captures the feeling of having a home and belonging, as felt by Sewell when she went back to Norfolk. Bringing her life full circle, she was buried in the graveyard of the Quaker Chapel at Lammas, the village next to Buxton, amid the landscape that was so vital to her family and work.

As did her fellow East Anglian, the painter Alfred Munnings — particularly in his early work — Sewell offered a detailed and authentic sense of rural life in her writing. Another aspect she didn’t shy away from was the cruelty of some people towards their animals.

‘Black Beauty was a book to encourage sympathy for horses in a world where they were used as tools, extensions of the machinery of the time,’ explains Jenny Caynes, curator of community history at the Museum of Norwich at The Bridewell.

‘The result of the book was an undeniable impact in terms of animal welfare, of shaping ideas of the general public and influencing public opinion.’

The novel is replete with pleas for an increased awareness of animal welfare — consider this passage, when Black Beauty explains ‘those who have never had a bit in their mouths, cannot think how bad it feels’. The book is, perhaps, tougher-minded than many might realise and can be seen as a striking metaphor for slavery and freedom, which didn’t go unnoticed when it was first published in America in the 19th century.

Sewell’s novel, therefore, is a powerful call to action, a hymn to the horse and an ode to Norfolk. It has a voice and a message that hasn’t diminished and, after all this time, seems unlikely to.

The tale of Mr Toad: From medieval instrument of torture to The Wind in the Willows

Toads might have been feared and reviled for 1,000 years, but the past century has seen us warm to these

Credit: ©Richard Cannon/Country Life Picture Library

The Queen's rocking-horse maker: ‘Many clients commission replicas of favourite horses’

Tessa Waugh meets Marc Stevenson of Stevenson Brothers rocking horses.

Curious Questions: Who invented the gin and tonic?

Gin and tonic is arguably the greatest cocktail ever created — but who first mixed these two seemingly unlikely ingredients together?

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

380 acres and 90 bedrooms on the £25m private island being sold by one of Britain's top music producers

380 acres and 90 bedrooms on the £25m private island being sold by one of Britain's top music producersStormzy, Rihanna and the Rolling Stones are just a part of the story at Osea Island, a dot on the map in the seas off Essex.

By Lotte Brundle

-

'A delicious chance to step back in time and bask in the best of Britain': An insider's guide to The Season

'A delicious chance to step back in time and bask in the best of Britain': An insider's guide to The SeasonHere's how to navigate this summer's top events in style, from those who know best.

By Madeleine Silver

-

How to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen

How to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen2025 marks the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen's birth. Here are exhibitions, events and more — happening across the UK — that mark the occasion.

By Annunciata Elwes

-

Unputdownable: 12 page turners to see you through the rest of the winter

Unputdownable: 12 page turners to see you through the rest of the winterFrom cookbooks to cricket, biographies to Sunday Times bestsellers, Country Life contributors name some of their favourite books from last year.

By Country Life

-

J.R.R. Tolkien: The life and times of the lord of the books

J.R.R. Tolkien: The life and times of the lord of the booksFrom a sentence born of an exhausting teaching job, J. R. R. Tolkien crafted a series of fantastical novels that, 50 years on from his death, still loom as large in our imagination as Sauron’s all-seeing eye, says Matthew Dennison.

By Matthew Dennison

-

Thomas Hardy's Wessex vs the real-life Dorset: Which bits are real, which dreams, and which are exact to the last stream and stile

Thomas Hardy's Wessex vs the real-life Dorset: Which bits are real, which dreams, and which are exact to the last stream and stileThomas Hardy’s depictions of a fictional Wessex and his own dear Dorset are more accurate than they may at first appear, says Susan Owens.

By Country Life

-

The English villages that are hotbeds of murder, intrigue and endless summer days — at least in the minds of novelists

The English villages that are hotbeds of murder, intrigue and endless summer days — at least in the minds of novelistsComforting yet complex, intriguing and alluring, the village setting is territory to which writers — and readers — will return again and again. Flora Watkins looks at how the customs, characters and communities of the English village have long sparked literary inspiration, from Jane Austen to Midsomer Murders.

By Flora Watkins

-

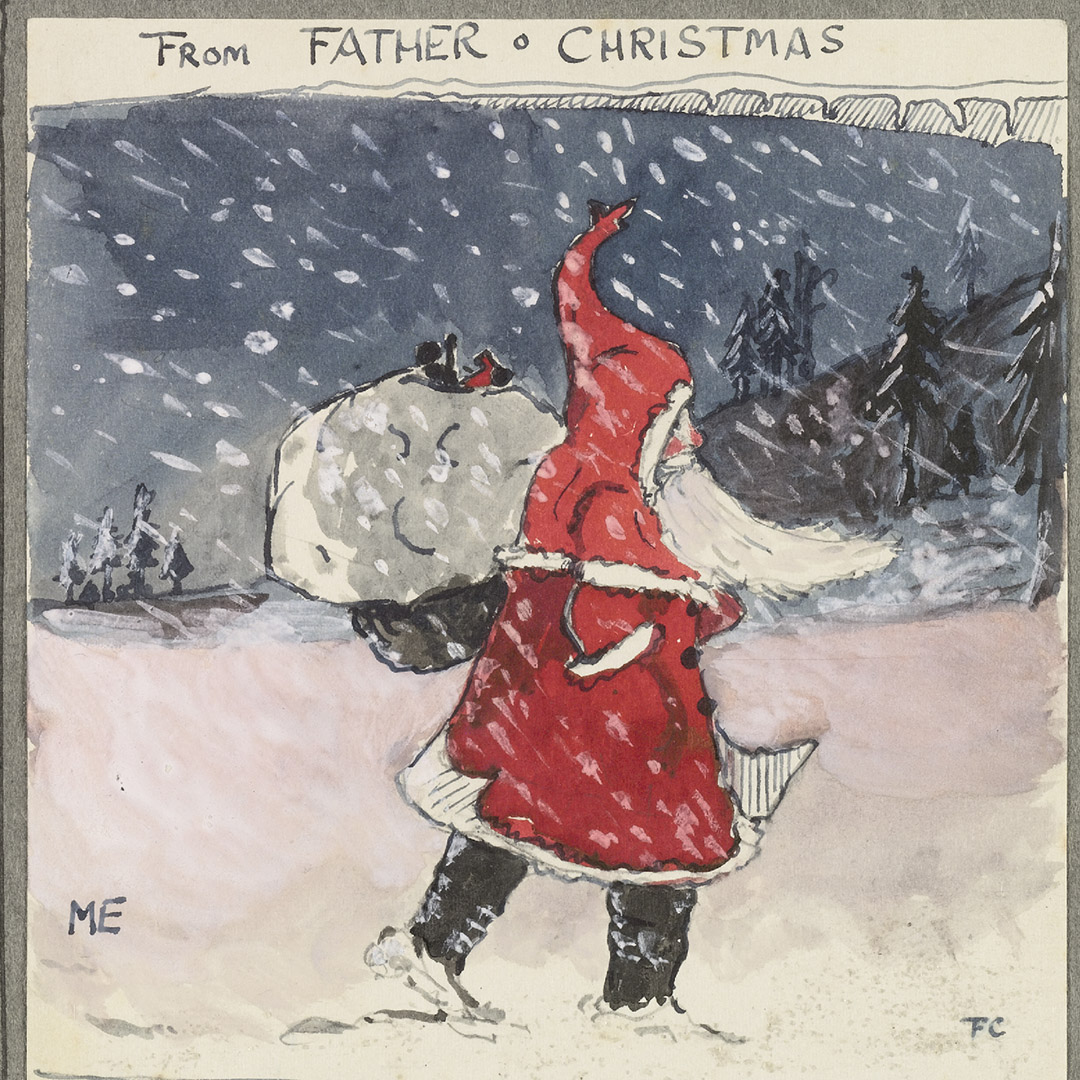

With love from Father Christmas: J.R.R. Tolkien's enchanting Christmas letters to his children

With love from Father Christmas: J.R.R. Tolkien's enchanting Christmas letters to his childrenFor nearly a quarter of a century, J. R. R. Tolkien sent his children elaborate letters and pictures from the North Pole. Ben Lerwill explores the penmanship, kindness and magic that went into Letters From Father Christmas.

By Country Life

-

The best characters created Charles Dickens, still utterly unforgettable even 150 years after his death

The best characters created Charles Dickens, still utterly unforgettable even 150 years after his deathCharles Dickens died 150 years ago, on 9 June 1870. Since then, Mr Micawber has become a byword for optimism, Scrooge for meanness and Uriah Heep for obsequiousness, and we still quote Mr Bumble’s ‘the law is an ass’. Rupert Godsal explains why these characters are so exuberantly unforgettable.

By Country Life

-

Charles Dickens timeline: The best of times, the worst of times

Charles Dickens timeline: The best of times, the worst of timesRupert Godsal paints the major events in the life and times of Charles Dickens, who died 150 years ago on 9 June, 1870.

By Country Life