Flatcoat retrievers: The dogs that are charming, endlessly happy and will do anything to capture your heart

Intelligent, devoted and adept at working all country, the flatcoated retriever is the Peter Pan of the dog world with a tail that never stops wagging, discovers Matthew Dennison. Photographs by Sarah Farnsworth.

In the paintings — six, in total — that H. Reginald Cooke, doyen of Edwardian flatcoated retriever breeders, commissioned from artist Maud Earl, his raven-black dogs each extend to an unglimpsed handler a single, limp-bodied grouse.

The dogs’ tails and legs are well feathered, autumn sunlight glancing off glossy coats. Their mouths are gentle, their heads erect, eyes alert, tails momentarily still. In the manner of Earl’s paintings, her subjects have a heroic elegance. These are supremely handsome gundogs and wonderfully reliable workers: a sportsman’s best companion.

This was how lifelong flatcoat aficionado Charles Eley eulogised the breed in his History of Retrievers, a book commissioned at the outbreak of the First World War, although publication was delayed until 1921. Eley celebrated flatcoats’ ‘beauty and charm… coupled with a natural docility and reciprocal love for man’.

Today’s owners agree. ‘They’re so charming, they absolutely capture your heart,’ Christiane Bunce, a flatcoat owner for 40 years, tells me. ‘They want to please, they’ll do anything to please, they’re wonderfully affectionate.’

With greater loyalty than accuracy, Eley claimed ‘the present moment… finds the flat-coated retriever as firmly entrenched as ever in the minds as well as in the hearts of sportsmen’. What had been true when Eley embarked on his book was no longer the case by 1921. In the final quarter of the 19th century, Kennel Club (KC) founder-chairman Sewallis Shirley MP had championed flatcoats vigorously, but Shirley had been retired for four years when, in 1903, the KC recognised the labrador as a breed in its own right.

Within less than a decade, a labrador belonging to the Duchess of Hamilton won Britain’s inaugural retriever championship. The breed’s rise to widespread popularity was swift — and, for the fortunes of flatcoats, devastating — and has continued. In 2018, the Kennel Club registered 36,526 labrador puppies. Flatcoat registrations for the same period totalled 1,146, a figure consistent over the past decade.

The sporting dog sans pareil of Edwardian England has never regained its erstwhile pre-eminence. ‘Very often, people have no idea what these dogs are,’ says Tiddy Redpath, the owner of a 10-year-old black flatcoat, Alfie, and eight-year-old liver-coloured Jambo, ‘especially the liver-coloured dog.’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

It was when looking at Edwardian photographs — shooting-party line-ups and family groups — found in her family home in North Wales, that Tanda Wilson-Clarke discovered her decision to acquire her first flatcoated retriever, in 1976, brought her great-grandparents’ favourite breed back into the family after half a century.

'They're eternal Peter Pans: they bounce up and down until the day they die’

‘A new keeper came to Vivod in the 1970s,’ Mrs Wilson-Clarke remembers. ‘He was flatcoat mad. This was what put flatcoats in my mind. Then, there was this wonderful coincidence — my first flatcoat, 43 years ago, was one the keeper bred.

‘Since then, every time we think of getting a new dog, we get out The Observer’s Book of Dogs as a family and we always come back to the flatcoat. I’ve had six so far and they’ve given me so much pleasure.’

As did a number of British gundogs, the flatcoated retriever emerged as a distinct breed in the second half of the 19th century, as a result of efforts by gamekeepers and sportsmen to develop the best possible dog for picking up a range of quarry over varied country. Its genetic mix almost certainly includes pointers, setters and Canadian water dogs, such as the Newfoundland, alongside more local gundog types.

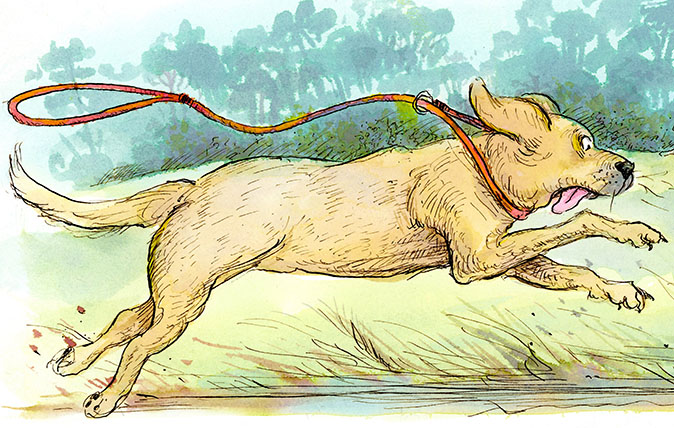

It’s this mix that accounts for the dog’s sleekness and speed, as well as its dense, but finely textured coat that appears to ripple as it runs. Early flatcoats were widely known as wavy-coated retrievers and were always black. Today, a liver colour is also possible — a result of selective breeding. In both colourways, the coat ought to lie as flat as possible to the body.

In Mrs Bunce’s long experience, the efforts of those early breeders were entirely successful. She has owned a dozen flatcoats and all have proved themselves adept at picking up pheasant, duck and partridge, with some better than others at retrieving smaller birds, such as woodcock, and all equally happy picking up rabbits and hares. ‘All of mine have been working dogs, but I prefer to work my dogs rather than my bitches simply on account of stamina. I prefer stockier, old-fashioned flatcoats to show-ring dogs, which can err towards gangliness.’

She cherishes memories of really impressive feats of retrieval: a dog called Gunner that, on a shoot on the Hardwick estate in Shropshire, in an overgrown area on the edge of a thicket, retrieved a woodcock overlooked by other dogs, despite its small size and the effectiveness of its camouflage; one of her three current dogs, eight-year-old Pepper, intently focused on an 80-yard retrieve across water; and the dog who did his best to return to her a Canada goose.

'They don’t give up. They don’t consider their job done until every bird is picked up.'

‘Flatcoats are absolutely in their element in water,’ says Mrs Wilson-Clarke. Yet both owners agree that one of the breed’s commendations is the dogs’ willingness to work all country. Spaniel-like, a well-trained flatcoat will brave dense cover. They are also air-scenters, working not only on, but above the ground, capable of spotting birds that are lodged in branches, hedges or tight among reeds.Among Mrs Wilson-Clarke’s previous dogs, several have pointed, too.

For Simon Fitzherbert-Brockholes, who owns seven flatcoats — six black dogs of the same bloodline and a liver-coloured dog called Finn — it was watching them at work that attracted him to the breed 25 years ago. ‘I loved watching the flatcoats bred by Joan Marsden [an eminent flatcoat breeder of the 1970s and 1980s and from whose line his black dogs originate]. I loved the way they looked in the field. Since then, I’ve always had a soft spot for the breed.’

Mr Fitzherbert-Brockholes points to a difference, on which many owners agree, between flatcoats and the more popular labrador. ‘A flatcoat doesn’t work like a labrador. They have a tendency to do their own thing, but with sound instincts. They will hunt independently and find birds on their own.’

Appropriately the adjective most often applied to working flatcoats is ‘dogged’. ‘They don’t give up,’ reveals Mrs Bunce. ‘They don’t consider their job done until every bird is picked up.’ Yet owners insist that their working methods have a lightness and elegance.

All of which isn’t to say that a flatcoat is born ready for work. Typically, training takes longer than that of a labrador or some spaniels. As a breed, flatcoats require time and patience in training, although a nature that is both intelligent and biddable means they aren’t resistant if properly handled.

Flatcoat enthusiasts love the breed’s ability to mature as trained gundogs without losing their puppyishness in other ways. They are lively, sociable, affectionate dogs, characterised by the KC as optimistic and friendly, ‘demonstrated by enthusiastic tail action’. After four decades, Mrs Bunce describes flatcoated retrievers as ‘eternal Peter Pans: they bounce up and down until the day they die’.

With this ebullience comes demonstrativeness. All owners agree that flatcoats are zealous lickers and great leaners. ‘They would prefer to be sellotaped to your face or hermetically attached to your inner thigh at all times,’ says Mrs Redpath.

‘They’re playful and puppy-like, springing into the air on all fours in delirious anticipation of food and fun.’ Even at work, awaiting instruction, Mrs Bunce has found that they press themselves against their handler’s legs, companionable in the shared endeavour of Man and dog.

A KC spokesman describes flatcoated retrievers to Country Life as ‘intelligent, friendly and affectionate, making them an ideal family companion. They have a playful temperament and are active dogs, well suited to country life with plenty of exercise and mental stimulation’.

'They really lift your spirits because they’re always happy'

Their record with children is a good one, too. Mrs Wilson-Clarke remembers a two-year-old bitch responding to one of her own newborn children in a manner ‘just like Nana in Peter Pan: she really looked after her’. Mrs Bunce’s daughter’s first word wasn’t mummy or daddy, but the name of the flatcoat bitch that kept assiduous watch over her cot and high chair.

That such sweet-tempered, handsome and companionable dogs continue to attract a relatively small number of owners seems surprising, but flatcoats aren’t a breed for the sedentary, nor are they suited to confined living quarters. These are dogs that want and require regular exercise.

‘They like to get out: they want to be doing,’ agrees Mrs Bunce, whose dogs are kenneled outside in summer and spend winter nights in the warmth of the back kitchen. Above all, it’s their energetic natures, not their size — similar to a labrador — that has contributed to flatcoats’ decline as a family pet.

Undeniable, however, are flatcoats’ health problems, of which all potential owners need to be aware. More than 50% of flatcoats die of cancer, according to a recent study, with a particularly high susceptibility to histiocytic sarcoma, an aggressive cancer that is often difficult to diagnose early enough for effective treatment. Research is ongoing, including by scientists working at the University of Cambridge, but the problem isn’t yet resolved. Sadly, very few of those who have owned flatcoat retrievers over a number of years have escaped without losing at least one dog to cancer.

‘The joy of flatcoats is that they really lift your spirits because they’re always happy,’ Mrs Wilson-Clarke summarises. Or, as a Victorian sportsman recorded of a particular flatcoat in 1880: ‘His eye was neither more nor less than a human one. I never saw a bad expression in it.’

For more details on the breed, visit www.flatcoated-retriever-society.org

Going flat out

- Gundog authority Col David Hancock identified the flatcoat’s distinguishing characteristics as ‘glamour and charm’.

- So highly valued were flatcoats by Edwardian shots that, in 1908, H. Reginald Cooke turned down an offer of 260gns for a champion dog. This is equivalent to £30,000 today.

- Named as ‘Dog of the Century’ by the National Canine Defence League, Swansea Jack was almost certainly a flatcoat retriever that, in the 1930s, in a number of different incidents, rescued as many as 27 people from Swansea Docks.

- Two key dogs in the establishment of today’s flatcoated retriever belonged to a gamekeeper, Mr J. Hull, in the 1860s. Appropriately, given the breed’s exuberance, they were called Old Bounce and Young Bounce.

Dachshunds: The undisputed kings of their castles, no matter the size (or species) of the other residents

Kate MacDougall gets the lowdown on dachshunds and discovers why their tiny stature doesn’t impinge on a ‘sausage’ dog’s zest

Curious Questions: What dog should Boris Johnson get as the new pet for No. 10 Downing Street?

Which breed makes the best gundog? The pros and cons of labradors, spaniels, terriers and more

Whether you own labradors, springers, cockers or a mix of all three, debate over which gundog is best has raged

Credit: John Holder

Nightmare stories from some of the naughiest gundogs in Britain

Although everyone likes to think their gundogs are impeccably behaved, Rupert Uloth observes that they’re capable of letting us down