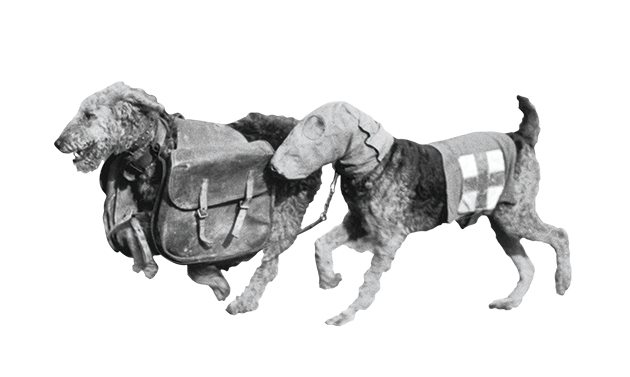

Dogs and the Second World War

The Second World War saw 7,000 dogs save countless lives – and we should pay tribute to them

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The War Office invites dog owners to lend their dogs to the Army,’ stated an appeal in British newspapers on May 5, 1941, despite a general feeling in Whitehall that asking for canine volunteers was a frivolous exercise in aid of a minor project. They were wrong on both counts.

Within two weeks, the British public had responded with 7,000 offers of dogs from owners looking to play their part. ‘My husband has gone, my sons have gone,’ one woman wrote. ‘Take my dog to help bring this cruel war to an early end.’ As Clare Campbell details in her new book, Dogs of Courage, by the end of the Second World War, the War Dogs’ Training School in Hertfordshire had dispatched a canine army to units all over the world. These most loyal and loving of companions not only boosted much-needed morale in times of desperation, but they saved countless lives.

One such recruit was yellow labrador Texas, of the No 4 Platoon, Royal Engineers, which was trained to detect anti-personnel mines. On March 24, 1945, Texas was part of a mine-breaching assault in the epic Rhine crossing, a task that was codenamed Operation Plunder along with other dogs, he was ferried across the river to clear mines in the villages Rees and Groin on the enemy-held side. Heavy mortar fire began almost immediately, but, according to reports, Texas continued to work under gunfire, undeterred by the blasts and devoted to the task at hand.

Although Texas never received official recognition for his bravery, Ricky, a Welsh collie from Kent, received the Dickin Medal for his actions in the Netherlands, where he had been sent in 1944 to clear mines from railway tracks and canal paths. Working through thick snow and on frozen ground, Ricky is reported to have brought cheer to the soldiers with his plucky spirit, fierce energy and determination.

On December 3, a mine exploded, killing the section commander and badly wounding Ricky. Despite the serious injury to his head and the shock of the explosion, the dog got straight back to work and found more mines before being taken away to have his wounds patched up.

Trained to scent mines and act as messengers, several war dogs were also chosen to assist airborne troops on D-Day and began their training with the 13th Parachute Battalion in 1944 the men carried chunks of meat in their pockets to encourage the dogs to follow them when jumping from the aircraft.

On June 6, three dogs fitted with parachutes, originally designed to drop bicycles, which opened by a static line as the dog exited the aircraft leapt from an Albemarle bomber over France under heavy anti-aircraft fire.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Accounts reveal one was seriously injured and another was caught in branches, but paradog Brian reported to his post on the edge of the Bois de Bavent, wounded, yet ready to work.

As well as playing their part abroad, dogs were also employed to work at home, rescuing civilians trapped under bomb-flattened buildings. Two German shepherds—Crumstone Irma, which received the Dickin Medal in 1945, and Crumstone Psyche along with their owner, Margaret Griffin, became particularly well known during the war for their search-and-rescue efforts.

Mrs Griffin read signals from Irma and Psyche as they picked up scent in the debris their ears would suddenly lie flat on their neck if they found a body and they would scratch away at the rubble excitedly upon finding someone alive. This small and determined team located a total of 233 people beneath the rubble, 21 of whom were still alive.

Perhaps the most miraculous survival story, however, is that of Judy, the English pointer who, formerly a mascot on board HMS Gnat and HMS Grasshopper, became the only official canine Second World War prisoner of war (PoW). After Grasshopper sank, Judy tracked down a fresh-water spring on the desert island where the survivors had washed up, but was subsequently caught up in the harsh conditions of the Gloegoer camp in Sumatra, where she was repeatedly kicked and stoned by her captors.

While incarcerated, she befriended Leading Aircraft-man (LAC) Frank Williams, who had been captured in Singapore in 1942, and the two became inseparable. When the Japanese ordered the PoWs back to Singapore, Judy was smuggled onto the cargo ship and, when torpedoes struck the boat, she swam around rescuing drowning prisoners, guiding them to floating debris. On their inevitable return to the Sumatra camp, LAC Williams became critically ill and later credited Judy, who sat loyally at his bedside, for giving him the determination to survive.

When they were liberated from the camp in 1945, both were nursed back to health and received bravery awards, with LAC Williams taking care of the pointer until her death in 1950.

An official briefing document on war dogs of 1942 firmly tells soldiers and handlers: ‘DON’T make friends with or pet any of these dogs.’ But, as Mrs Campbell points out in her book, with companions of such character and courage by the troops’ side, ‘that was perhaps asking the impossible’.

‘Dogs of Courage: When Britain’s Pets Went to War 1939–45’ by Clare Campbell is published by Corsair (£14.99)

Katy Birchall is a journalist and the author of several young adult and teen novels, including The It Girl series and the Hotel Royale series. She has written a retelling of Jane Austen’s Emma for the Awesomely Austen series and the Netflix spin-off novel Sex Education: The Road Trip. She is also the author of several romantic comedies for adults including The Secret Bridesmaid and The Wedding Season. She writes romantic fiction for young adults under the name Ivy Bailey, romantic-comedy under the name Katrina Logan, and romantic sports fiction for adults under Katherine Reilly. She lives in London with her husband, daughter and rescue dog.