Curious Questions: What are unicorn horns made of? And why are we so fascinated by these mythical beasts?

Whether it be in a coat of arms, in a piece of art or emblazoned on the backpack of a child, barely a day goes by when we don’t encounter a unicorn. Ian Morton explores the power this mythical creature has held over us since the dawn of civilisation.

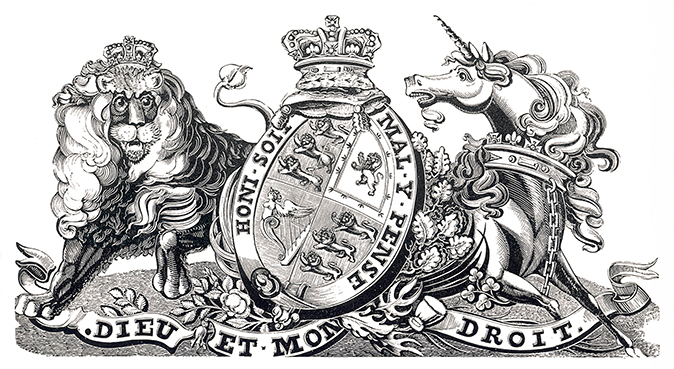

Consider our royal coat of arms: the rampant lion, chosen by Richard I to symbolise England’s power, turns his head directly towards us, snarling and confident. The rearing unicorn, earlier adopted by William I for his Scottish display, looks across the escutcheon to watch the lion. As well he might, for the two are traditional enemies.

Their heraldic reconciliation was designed to symbolise the unification of England and Scotland – likewise enemies of old – when James VI of Scotland became James I of England in 1603.

The unicorn is Scotland’s beast. From the 12th century until 1603, the royal coat of arms of the Kingdom of Scotland was supported by unicorns on either side and, on his accession to the English throne, James displaced the unicorn on the right side of the shield with a lion. The two beasts swapped sides when Victoria came to the throne in 1837 and the modern version was adopted.

So why is it Scotland’s beast? Primarily because of its place in Celtic mythology, in which the unicorn was revered as a symbol of innocence, purity, happiness and a reputation for healing. However, belief in the horned horse is as old as civilisation and has spanned many cultures. What appear to be horned-horse images have been found in cave paintings in France, South Africa and South America.

The unicorn was worshipped in Babylon from 3500BC. Chinese history relates the appearance in 2900BC of Chi’i lin, a gentle giant of a unicorn with a 12ft horn, with later sightings said to have included an encounter with Confucius himself. Greece, Rome, Persia and Judea likewise revered a similar magical creature with healing powers.

The unicorn was credited with enormous strength, courage and the ability to drive off even an elephant, yet it was selfless. Ancient tradition told that, if a snake poisoned a waterhole, the unicorn would purify the water on behalf of all other animals by dipping in its horn. The moral that a powerful and noble being should help others gave it immense appeal in the age of medieval chivalry.

'There was a conspiracy of silence that sustained the tusks’ high value as unicorn horns... Elizabeth I herself accepted the gift of a ‘unicorn horn’ valued at £10,000'

In Western Europe, a biblical allegory told of a small unicorn laying its head in the lap of the Virgin Mary, which led to regular and approved appearances in religious art.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

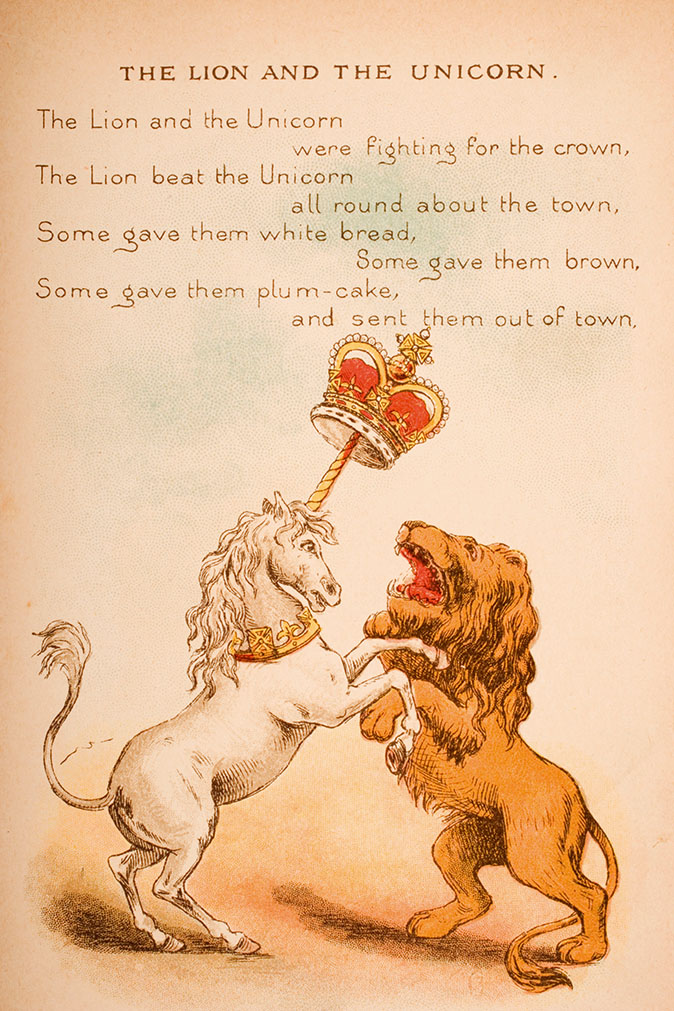

The notion that the lion and the unicorn were entrenched enemies dates from Babylonian days and remained current in medieval literature. According to legend, when the unicorn encountered the lion, he lowered his head and galloped in for the kill. Yet the lion had a method, well known to early chroniclers, of drawing his enemy into an arboreal trap. In the 16th century, both Shakespeare (in Julius Caesar) and Edmund Spenser (in The Faerie Queene) alluded to it.

Four years after England and Scotland united under one crown, the first natural history to be printed in English, the Historie of Fourefootid Beasts, published by the Rev Edward Topsell, declared: ‘As soon as ever the lion seeth a unicorn, he runneth to a tree for succour, so that when the unicorn maketh force at him, he may not only avoid his horn but also destroy him, for the unicorn, in the swiftness of his course, runneth against the tree wherein his sharp horn sticketh fast, that when the lion seeth the unicorn fastened by his horn, without all danger he falleth upon him and killeth him.’

This symbolic enmity continued into Victorian times. When Lewis Carroll referred to the lion and the unicorn ‘fighting for the crown’ in Through the Looking-Glass in 1871, political observers recognised he was alluding to the bitter rivalry between Gladstone and Disraeli. Historian Richard Aldous chose the two beasts for the title of his 2007 book on the politicians’ mutual loathing.

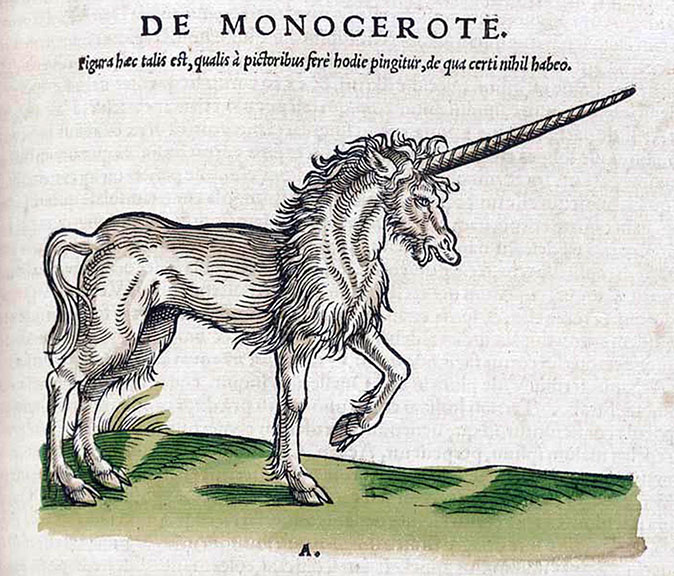

As illuminated scripts and stained glass gave credence to the unicorn and congregations would be familiar with it, Topsell – a Cambridge BA and career Anglican clergyman – clearly had no compunction about verifying the beast’s existence. His Historie claimed the existence of an array of hideous creatures drawn from the imaginative bestiaries of the ancient world, all of which he claimed to be ‘the wonderful work of God in their Creation, Preservation and Destruction’.

Nightmare illustrations from woodblocks provided by William Jaggard, official printer to the City of London, included a huge sea serpent wrapped round a sailing ship, a ‘Boas’ swallowing a child, a human-headed ‘Mantichora’, a ‘Bear Ape’ with shaggy animal body and human head, an ‘Aegopithecus’, having a human torso with a goat’s head and legs, a variety of dragons with and without wings, a gorgon and an unidentified monster with the head and breasts of a woman, a body covered in scales, front legs equipped with claws and rear legs with hooves.

All fell within Topsell’s claims for ‘true and lively’ representation and ‘the wonderful work of God’, their function being to frighten sinners. In such terrifying company, the unicorn offered quaking supplicants some welcome relief and Topsell claimed that its horn, crushed and drunk in water, would ‘wonderfully help against poyson’.

Such credulity was no doubt helped by the fact that 'unicorn horns' were readily available. They were, in fact, narwhal tusks brought back from northern seas – and if the good cleric was aware of this, he simply ignored it.

There was, in any event, a conspiracy of silence that sustained the tusks’ high value as unicorn horns. Scottish harbour folk were clearly implicated in this, and their efforts were enormously successful with the result that the the myth was accepted at face value at every level of society. Elizabeth I herself accepted the gift of a ‘unicorn horn’ valued at £10,000, and many a great house acquired an example that was displayed with pride.

Henry Ferrers, the aristocratic owner of Baddesley Clinton, Warwickshire, recorded in his diary for March 1628 a problem in remodelling his Great Chamber. He regretted that ‘the unicorn is not set up for the crest, and is as I think to big and to upright [sic]’ to feature above the fireplace as he desired. To this day the 10ft ‘unicorn horn’, fluted and yellow with age, stands instead in a corner of the room.

[collections]

Toby Keel is Country Life's Digital Director, and has been running the website and social media channels since 2016. A former sports journalist, he writes about property, cars, lifestyle, travel, nature.