The ten best dogs in literature

Man’s best friend has taken a starring role in stories since we first put pen to paper, playing nanny to the children, helping to solve mysteries and trotting down the Yellow Brick Road. Claire Jackson chooses 10 great canines from literature.

Our four-legged friends have featured prominently in cultural life since representations of dogs were first painted onto cave walls. Dogs – as hunters, protectors and companions – have been a rich source of inspiration to writers, who have often used them as a device to comment on the human condition.

The relationship with our furry family members is often highly emotional, which has been grist to the mill for several authors. Rudyard Kipling accurately captures this intensity when he warns of the dangers of ‘giving your heart to a dog to tear’ in his tear-inducing poem The Power of the Dog. The problem is that ‘when the fourteen years which Nature permits’ have passed, the pain of losing ‘the body that lived at your single will’ and ‘the spirit that answered your every mood’ is beyond terrible.

Not all portrayals are as heavy- hearted. Literature permits the impossible and, with that, dogs have been given the ability to speak, to guard and to carry out all sorts of roles that are outside the parameters of reality.

From the fantastic and the frankly bizarre to the delightful and the gut-wrenching, literary canines have amused and impressed since the dawn of the printed word.

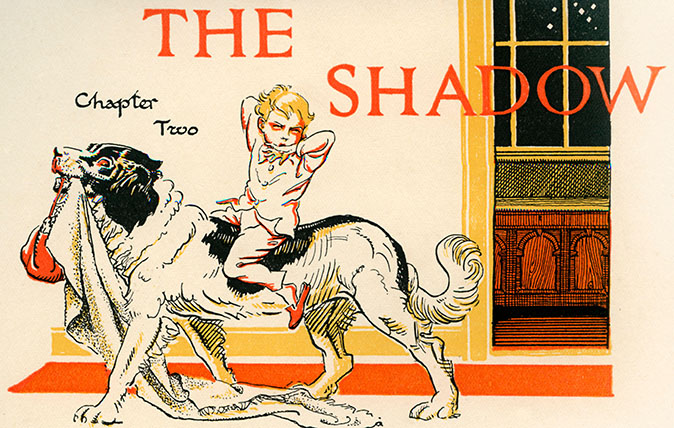

Nana – Peter Pan by J. M. Barrie

Before Mary Poppins, there was Nana, a ‘prim Newfoundland dog’ who ‘proved to be quite a treasure of a nurse’. Nana’s charges were Wendy, John and Michael Darling and she looked after them expertly, despite Mr Darling’s concerns about what the neighbours might think.

Nana was prepared for anything – ‘she carried an umbrella in her mouth in case of rain’ – and ‘of course her kennel was in the nursery’, until that fateful day when Mr Darling chained her up outside and Peter Pan flew in through the window, ushering the children away to Neverland. On their return, we are assured that dear old Nana was reinstated to the nursery, where she lived to a ripe old age.

Flush – Flush: A Biography by Virginia Woolf

Have you ever wondered what your canine companion would say about you, if he or she had the capacity? Flush is the writer Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s cocker spaniel and – with a little help – he shared insights from his life in a charming biography.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Woolf mixes fact with fiction, using Barrett Browning’s two poems on dogs (To Flush, My Dog and Flush or Faunus) as the basis for the prose.

We follow Flush from his early life in the country to his adoption by Browning, his owner’s confinement by illness and her elopement (with a man he attempts to bite). There is action aplenty as Flush is dognapped (and subsequently rescued) and travels to Italy.

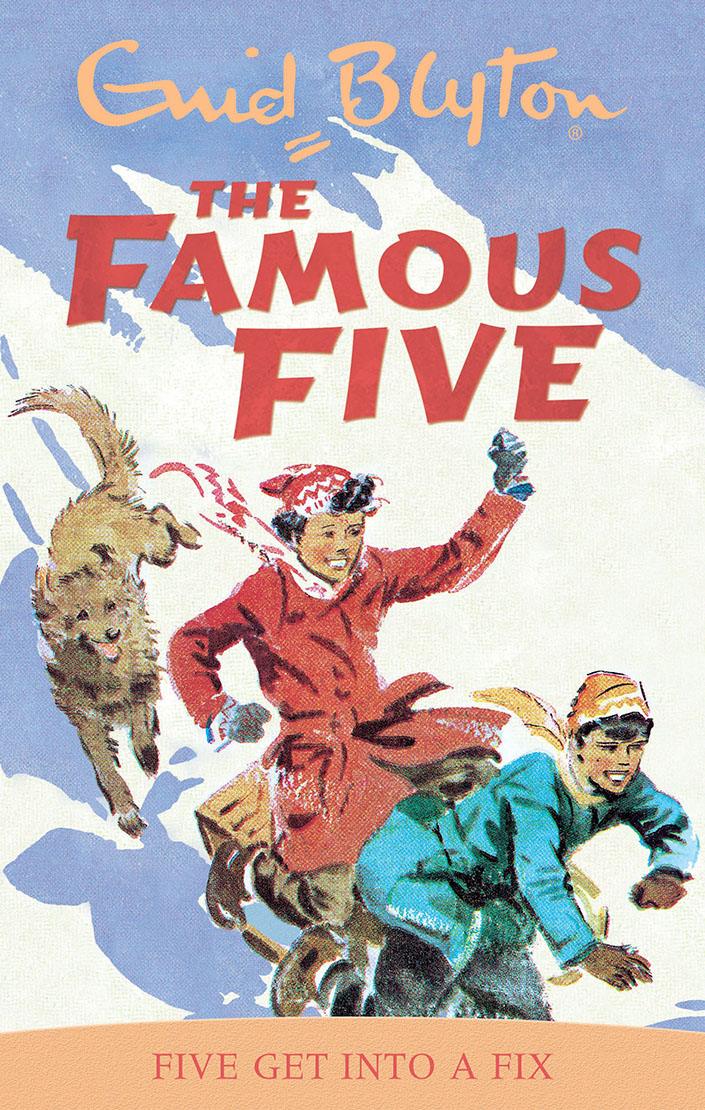

Timmy - The ‘Famous Five’ stories by Enid Blyton

The loveable Timmy from Blyton’s series plays a key part in the quintet’s escapades, be it sniffing out smugglers or identifying secret trails. For Anne, Dick, Julian and George, to whom he belongs, Timmy is guard dog and companion. In the first book, Five on a Treasure Island, we learn that George’s parents have forbidden her to keep Timmy, so he lives with a fisher boy in the village. However, after their first successful brush with fighting crime, Timmy is allowed his rightful place in the house.

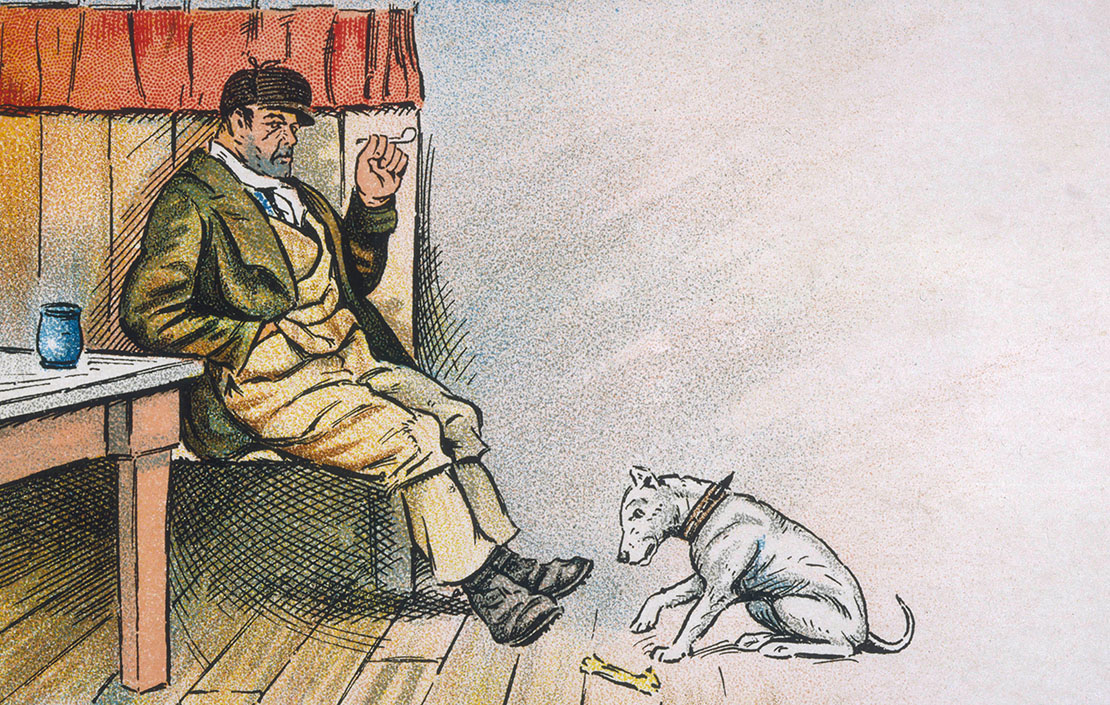

Bullseye – Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens

The villainous Bill Sikes had a ‘white-coated, red-eyed dog’ whose visage was as unattractive as his owner’s. Bullseye is described as ‘shaggy’, ‘with his face scratched and torn in twenty different places’ and as having a violent temperament, no doubt due to the treatment he receives.

The dog is ultimately punished for his loyalty; fearing that the animal’s existence will give him away, Sikes vows to drown Bulls-eye, who, apparently sensing his fate, runs away.

When Sikes is hanged, Bullseye issues a ‘dismal howl’ and jumps after his master, falling into a ditch and ‘striking his head against a stone, dashed out his brains’.

The dark Dickensian language, although gruesome, is effective in turning Bullseye into a representation of Sikes’s misdemeanours.

Fluffy – Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone by J. K. Rowling

Three heads are better than one – except in the case of magical beasts, as Harry, Ron and Hermione discover in the first instalment of the ‘Harry Potter’ series. Fluffy, a three-headed dog, is guarding the titular object, but he has a simple vice: a few bars of music and all three heads are happily snoozing, leaving our heroes to face their next challenge.

This isn’t the only notable dog in the books. Fang, Hagrid’s slobbery great dane, appears sporadically throughout. Despite his enormous size, Fang is gentle; when Malfoy is sent to the forbidden forest on detention, he asks for the dog for protection and is told: ‘Ah warn you, he’s a coward.’

Harry’s godfather Sirius Black, an illegal animagus, can also transform into a big, black dog known as Padfoot. On one occasion, having escaped from Azkaban prison, he recklessly uses the form to see Harry off to school at King’s Cross.

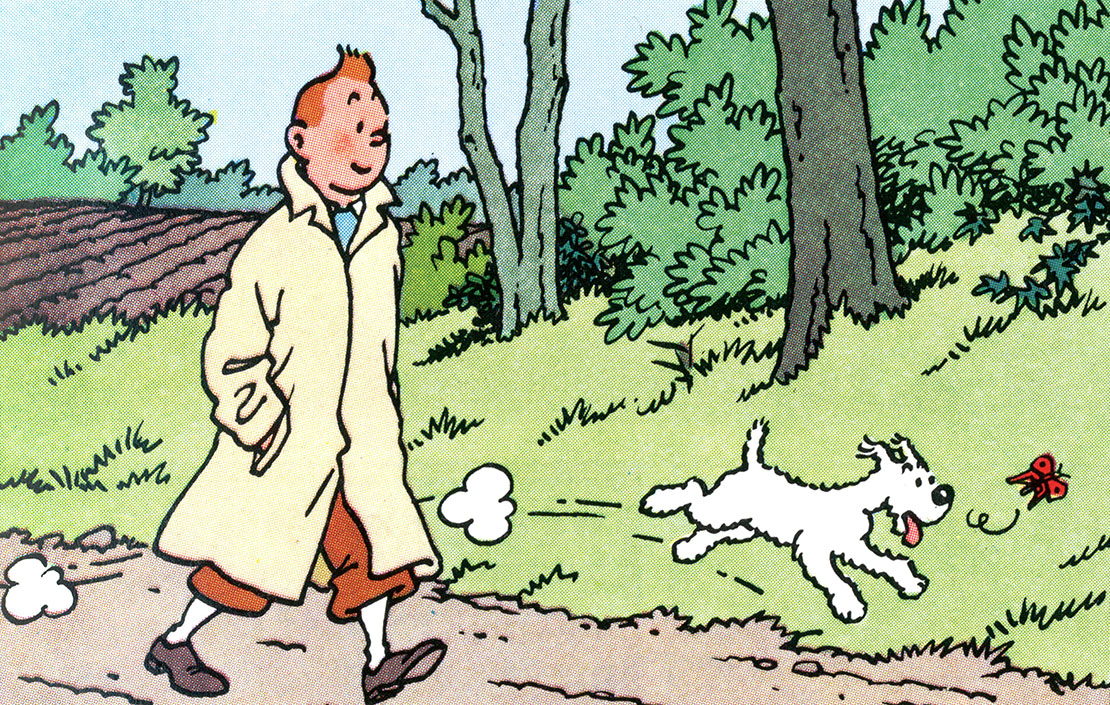

Snowy – The Adventures of Tintin by Hergé

Tintin’s sidekick is a wire fox terrier called Snowy, who was inspired by a real-life dog that the cartoonist saw at a cafe while creating the series. Milou, as he is known in the French-language versions, became Snowy for the English translations as the name fitted neatly into the speech bubbles – as well as describing the dog’s white coat.

Snowy is loyal, witty and brave (unless faced with spiders). He also has a penchant for whisky and, more befitting of his species, bones.

Hairy Maclary – Hairy Maclary From Donaldson’s Dairy by Lynley Dodd

Hairy Maclary is one of a number of dogs that star in the witty series loved by children and adults alike. In the first book, we meet Hairy Maclary, a small terrier of mixed breed, who runs riot over the village until he faces his arch-enemy, Scarface Claw the cat. Dame Lynley’s rhyming verse cleverly introduces each dog with a delightful description, including the dachshund Schnitzel Von Krumm ‘with a very low tum’, dalmatian Bottomley Potts ‘all covered in spots’, English mastiff Hercules Morse ‘as big as a horse’, greyhound-whippet-cross Bitzer Maloney ‘skinny and boney’ and old English sheepdog Muffin McLay, who looks like ‘a bundle of hay’.

Shock – The Rape of the Lock by Alexander Pope

This satirical poem is based on a real-life incident in which a British nobleman cut a lock of hair from the head of a woman he was in love with – without her consent.

The text’s heroine is Belinda, who has a dog called Shock, thought to be a small breed as the opening references ‘lap-dogs’ who ‘give themselves the rousing shake’. The style of prose is inspired by both classical and medieval epics and emphasises the absurdity of the attack.

We all need an alarm clock like Shock, who, when he thinks Belinda has overslept, ‘leap’d up, and wak’ed his mistress with his tongue’.

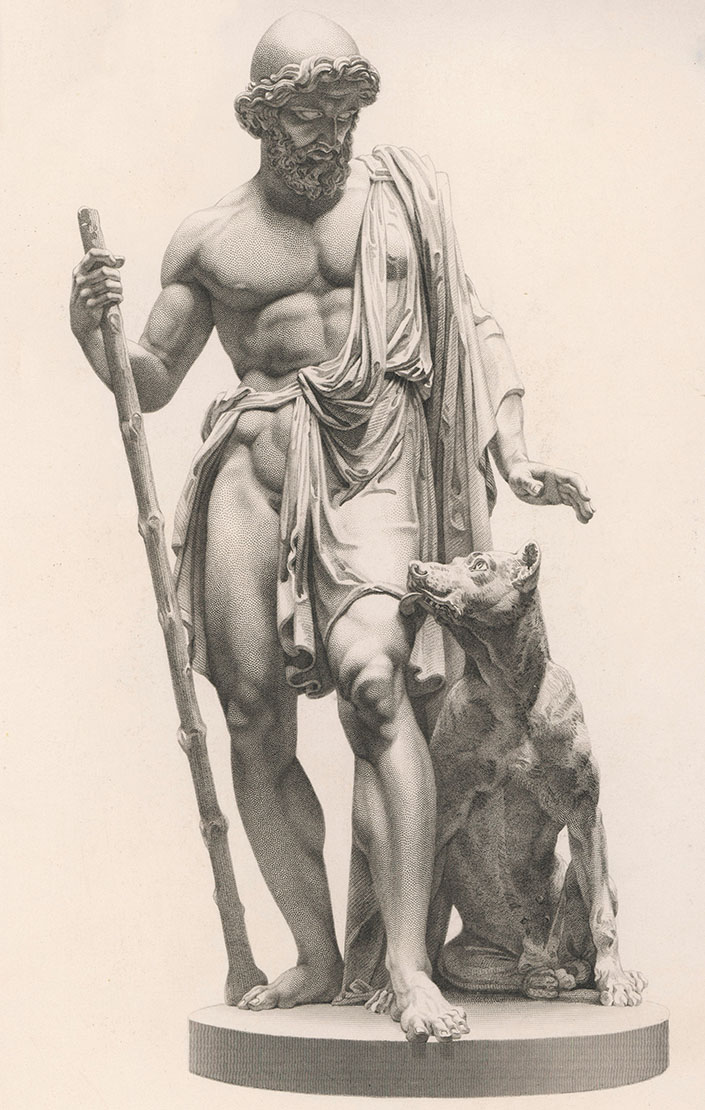

Argos – The Odyssey by Homer

Argos, once fleet of foot and a superior tracker, has been left neglected while his master Odysseus fights in Troy. On his return, Odysseus finds his house and wife under attack and must enter in secret to spring a surprise rescue.

Argos, now weak and ill (and described as infested with fleas and lying in cow manure), manages to wag his tail in recognition of his former companion. Like Bill Sikes, Odysseus knows his pooch will give his presence away, so he ignores the animal. Unlike Sikes, however, the rejection hurts both human and dog and, ultimately, Argos dies of a broken heart. And you thought Marley and Me was moving.

Toto – The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum

Dorothy finds herself unwittingly immersed in the fantastical, as she and her dog Toto are swept away from their Kansas home by a cyclone. Toto is a ‘little black dog with long silky hair and small black eyes that twinkled merrily on either side of his funny, wee nose’.

He appears as a small breed, thought to be a cairn or a Yorkshire terrier, in early editions of the book, illustrated by W. W. Denslow.

In the first of the ‘Oz’ novels, unlike several of the other creatures, Toto cannot speak ‘human’, but Baum changes tack and the little dog is given his own narrative in later stories.

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Our six favourite nannies, in fiction and film

Whether they invoke fond or fearful memories in real life, the nannies of fiction are kind – even magical –

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Seven of the UK’s best Arts and Crafts buildings — and you can stay in all of them

Seven of the UK’s best Arts and Crafts buildings — and you can stay in all of themThe Arts and Crafts movement was an international design trend with roots in the UK — and lots of buildings built and decorated in the style have since been turned into hotels.

By Ben West

-

A Grecian masterpiece that might be one of the nation's finest homes comes up for sale in Kent

A Grecian masterpiece that might be one of the nation's finest homes comes up for sale in KentGrade I-listed Holwood House sits in 40 acres of private parkland just 15 miles from central London. It is spectacular.

By Penny Churchill

-

How to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen

How to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen2025 marks the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen's birth. Here are exhibitions, events and more — happening across the UK — that mark the occasion.

By Annunciata Elwes

-

Unputdownable: 12 page turners to see you through the rest of the winter

Unputdownable: 12 page turners to see you through the rest of the winterFrom cookbooks to cricket, biographies to Sunday Times bestsellers, Country Life contributors name some of their favourite books from last year.

By Country Life

-

J.R.R. Tolkien: The life and times of the lord of the books

J.R.R. Tolkien: The life and times of the lord of the booksFrom a sentence born of an exhausting teaching job, J. R. R. Tolkien crafted a series of fantastical novels that, 50 years on from his death, still loom as large in our imagination as Sauron’s all-seeing eye, says Matthew Dennison.

By Matthew Dennison

-

Thomas Hardy's Wessex vs the real-life Dorset: Which bits are real, which dreams, and which are exact to the last stream and stile

Thomas Hardy's Wessex vs the real-life Dorset: Which bits are real, which dreams, and which are exact to the last stream and stileThomas Hardy’s depictions of a fictional Wessex and his own dear Dorset are more accurate than they may at first appear, says Susan Owens.

By Country Life

-

The English villages that are hotbeds of murder, intrigue and endless summer days — at least in the minds of novelists

The English villages that are hotbeds of murder, intrigue and endless summer days — at least in the minds of novelistsComforting yet complex, intriguing and alluring, the village setting is territory to which writers — and readers — will return again and again. Flora Watkins looks at how the customs, characters and communities of the English village have long sparked literary inspiration, from Jane Austen to Midsomer Murders.

By Flora Watkins

-

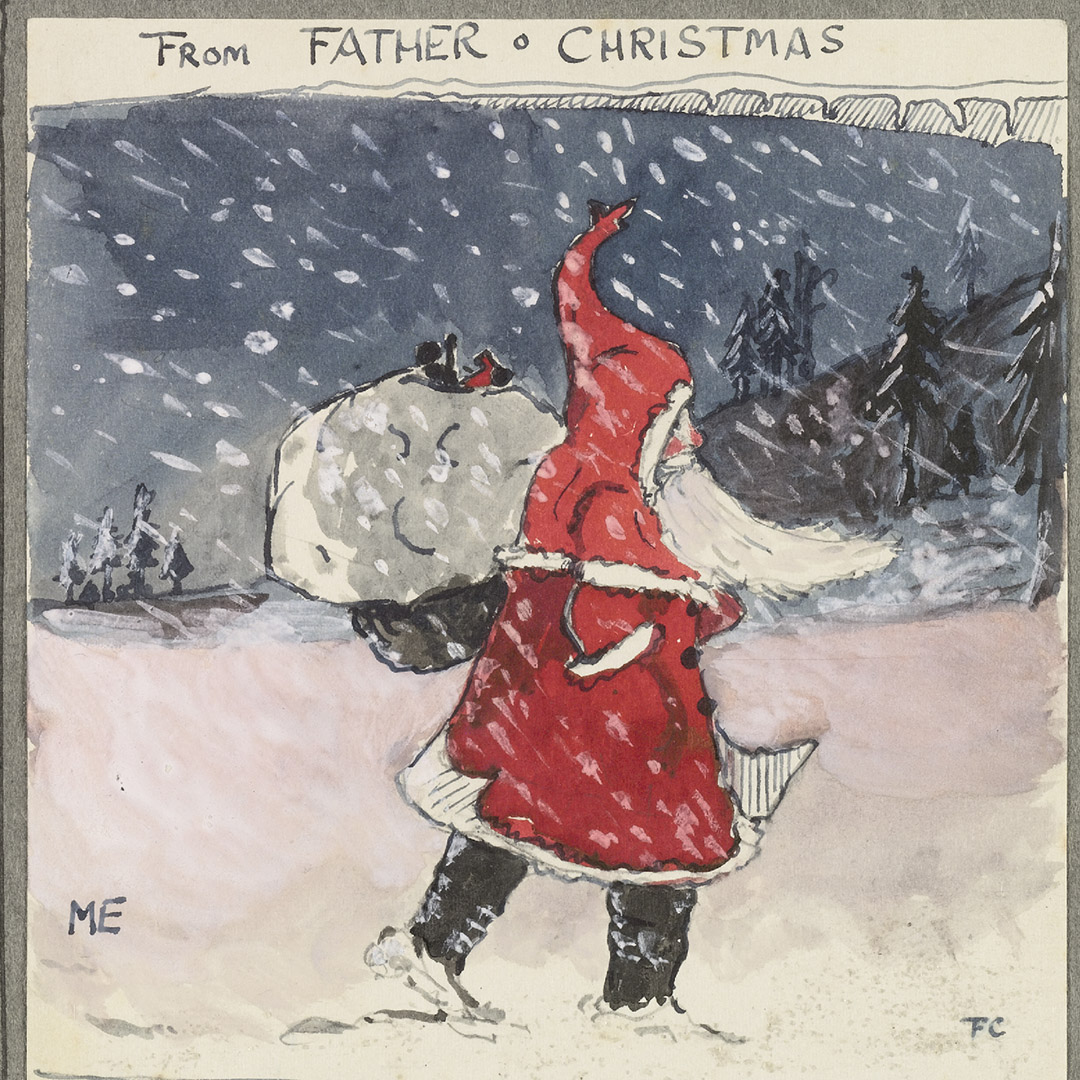

With love from Father Christmas: J.R.R. Tolkien's enchanting Christmas letters to his children

With love from Father Christmas: J.R.R. Tolkien's enchanting Christmas letters to his childrenFor nearly a quarter of a century, J. R. R. Tolkien sent his children elaborate letters and pictures from the North Pole. Ben Lerwill explores the penmanship, kindness and magic that went into Letters From Father Christmas.

By Country Life

-

The best characters created Charles Dickens, still utterly unforgettable even 150 years after his death

The best characters created Charles Dickens, still utterly unforgettable even 150 years after his deathCharles Dickens died 150 years ago, on 9 June 1870. Since then, Mr Micawber has become a byword for optimism, Scrooge for meanness and Uriah Heep for obsequiousness, and we still quote Mr Bumble’s ‘the law is an ass’. Rupert Godsal explains why these characters are so exuberantly unforgettable.

By Country Life

-

Charles Dickens timeline: The best of times, the worst of times

Charles Dickens timeline: The best of times, the worst of timesRupert Godsal paints the major events in the life and times of Charles Dickens, who died 150 years ago on 9 June, 1870.

By Country Life