Curious Questions: Why does Scotland have 30,000 lochs, but only one lake?

A moment's reflection on a cancelled pub quiz gets Martin Fone wondering about Scotland's only lake.

Consulting my diary, that testament to lost opportunities and thwarted plans, I see that I should having been participating in a pub quiz, another, admittedly minor, victim of the pandemic. The consequences are that a well-deserving cause has missed out on the chance of raising some much-needed funds and I will not be able to pit my wits against friends and neighbours in a convivial atmosphere.

When I participated in pub quizzes, I found that with advancing years I had to console myself with the fact that I had taken part and given my grey cells a workout, my power of instant recall having diminished to such an extent that any pretensions I may have had to prowess having long since disappeared.

On the plus side, certain questions cropped up with astonishing regularity. I have lost count of the number of times I have had to name the only lake in Scotland. As the product of a Gradgrindian educational system, unsullied by the ephemera of celebrity, pop, film and television, I would write down the Lake of Menteith with a sense of smug satisfaction, knowing I had a point in the bag.

Quiz compilers, though, soon learn the merits of precision in their language, if only to keep the pedants at bay. When the answer was revealed, the omission of the adjective 'natural' before the word 'lake' would incite certain participants to press the claims of the Lake of Hirsel, Pressmennan Lake, and Lake Louise — all Scottish but, crucially, man-made bodies of water. There are no holds barred when a prize is at stake.

A narrow focus on facts, though, often means that we lose sight of the bigger picture. What is it about Scotland’s only natural lake that marks it out from the 30,000 or so freshwater lochs in the country? Is there some unusual topographical or geological phenomenon that sets it apart? The answer, it seems, is more etymological than geological which — with all due respect to geologists — makes it even more fascinating in my book.

Situated on the Carse of Stirling, the flood plain of the upper reaches of the rivers Forth and Teith, the lake is 2.4 kilometres long, covers an area of 252 hectares and at its deepest plunges 23 metres down although its average depth is just over six metres. Renowned for the quality of its rainbow and brown trout it is said to offer some of the finest sport for anglers in the country.

Of the small islands on the lake, Inchmahome is the largest and most interesting, home to an abbey founded in 1238 by Walter Comyn. Its ruins can still be seen today. The abbey played host to a number of famous visitors including Robert the Bruce who is said to have sought refuge there on three occasions, in 1305, 1308 and 1310, and Mary Queen of Scots who turned up in 1547.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Mary’s visit was out of necessity, fleeing as a four-year old with her mother, Mary of Guise, from the English army who had routed the Scottish troops at the Battle of Pinkie, in what was dubbed the War of The Rough Wooing. The war, which lasted nearly eight years, was an English attempt to weaken the Scots’ alliance with France and force the infant Mary to accept the hand of Henry VIII’s son, the future Edward VI. After hiding for three weeks in Inchmahome, the two Marys were smuggled out to France.

Until the 19th century the lake was a loch. In Blaeu’s Atlas of Scotland, published in 1654, it appears as Loch Inche mahumo, taking its name from abbey’s island. By 1685, though, its name had changed, several documents over the next century referring to it as Loch of Menteith. This was the name given to the stretch of water by James Stobie in his map of the Counties of Perth and Clackmannan, published in 1783. To muddy the waters further, Walter Scott referred to it as Lough of Menteith in a letter dated between 1817 and 1819, while the locals, according to a later commentator, introduced another name into the mix, the Loch o’Port.

What differentiated the name given to the lowland waters known as Menteith from those of other lochs, such as Lomond, Ness, and Fyne, was the use of the preposition, of. Regrettable as it may seem to us nowadays, English was regarded amongst educated Scots in the 18th and 19th centuries as the language of sophistication and learning. Leading lights of the Scottish Enlightenment, David Hume and James Beattie, went so far as to compile lists of what they called 'Scottisms' which should be avoided when putting quill to parchment.

When it came to stretches of water, the practice was to replace the Scottish Gaelic word loch with lake in written documents or, for clarity, to add 'lake of' in front of the Scottish name. Loch Lomond became the lake of Loch Lomond, for example, in Patrick Graham’s Sketches of Perthshire, published in 1806, a guidebook written 'at the urging of some travelling gentlemen'.

Although based on the area around Loch Katrine, Sir Walter Scott still called his narrative poem The Lady of the Lake (1810). However, when this formulation was applied to Menteith, the lake of the Loch of Menteith proved to be a bit of a mouthful. The resolution, so the theory goes, was to delete the reference to a loch completely.

Confusingly, it has also taken on a slightly different name at times. A printed reference to the 'Lake of Monteith' appeared in John Pinkerton’s grandiloquently entitled book, Modern Geography; A Description of the Empires, Kingdoms, and Colonies; with their Oceans, Seas, and Isles; in All Parts of the World, published in1803. There he described 'the lake of Monteith' as 'a beautiful small lake, about five miles in circumference, with two woody isles'. Patrick Graham’s guidebook was equally as effusive of the area’s charms: 'Looking eastward, you have the windings of the Forth, deep skirted with woods, in bird’s-eye perspective; the lake of Monteith.' The National Library of Scotland even has a digitally-archived copy of an 1866 book called 'Summer at the Lake of Monteith', penned by the then-stationmaster, P. F. Dun. That alternate spelling is almost never seen now.

What almost certainly sealed the fate of Menteith’s name was its namecheck in Sir Walter Scott’s Rob Roy, an enormously popular book published in 1818, which helped fuel the area’s nascent tourist industry. There, in a passage which closely echoes Graham’s description, he wrote, 'while far to the eastward the eye caught a glance of the lake of Menteith.'

The first Ordnance Survey map of the area, produced in 1866, marked the expanse of water as the lake of Menteith and that has remained its idiosyncratic name ever since. Ironically, the 1863 survey notes recorded a burn, Goudie Water, as 'issuing from the Loch of Mentieth'. Old habits die hard.

Loch or lake, it is set in a beautiful part of Scotland and is well worth a visit.

Red telephone boxes: 7 fantastic alternative uses for a British icon

Distinctly British, but rendered obselete by the march of the mobile, the red telephone box is finding new purpose, as

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.

-

Diamonds are everyone's best friend: The enduring appeal of one of Nature's sparkliest treasures

Diamonds are everyone's best friend: The enduring appeal of one of Nature's sparkliest treasuresEvery diamond has a story to tell and each of us deserves to fall in love with one.

By Jonathan Self

-

RHS Chelsea Flower Show: Everything you need to know, plus our top tips and tricks

RHS Chelsea Flower Show: Everything you need to know, plus our top tips and tricksCountry Life editors and contributor share their tips and tricks for making the most of Chelsea.

By Amie Elizabeth White

-

Curious Questions: Why do golf balls have dimples? And why are tennis balls furry?

Curious Questions: Why do golf balls have dimples? And why are tennis balls furry?As the weather picks up, millions of us start thinking about dusting off our golf clubs and tennis rackets. And as he did so, Martin Fone got thinking: why aren't the balls we use for tennis and golf perfectly smooth?

By Martin Fone

-

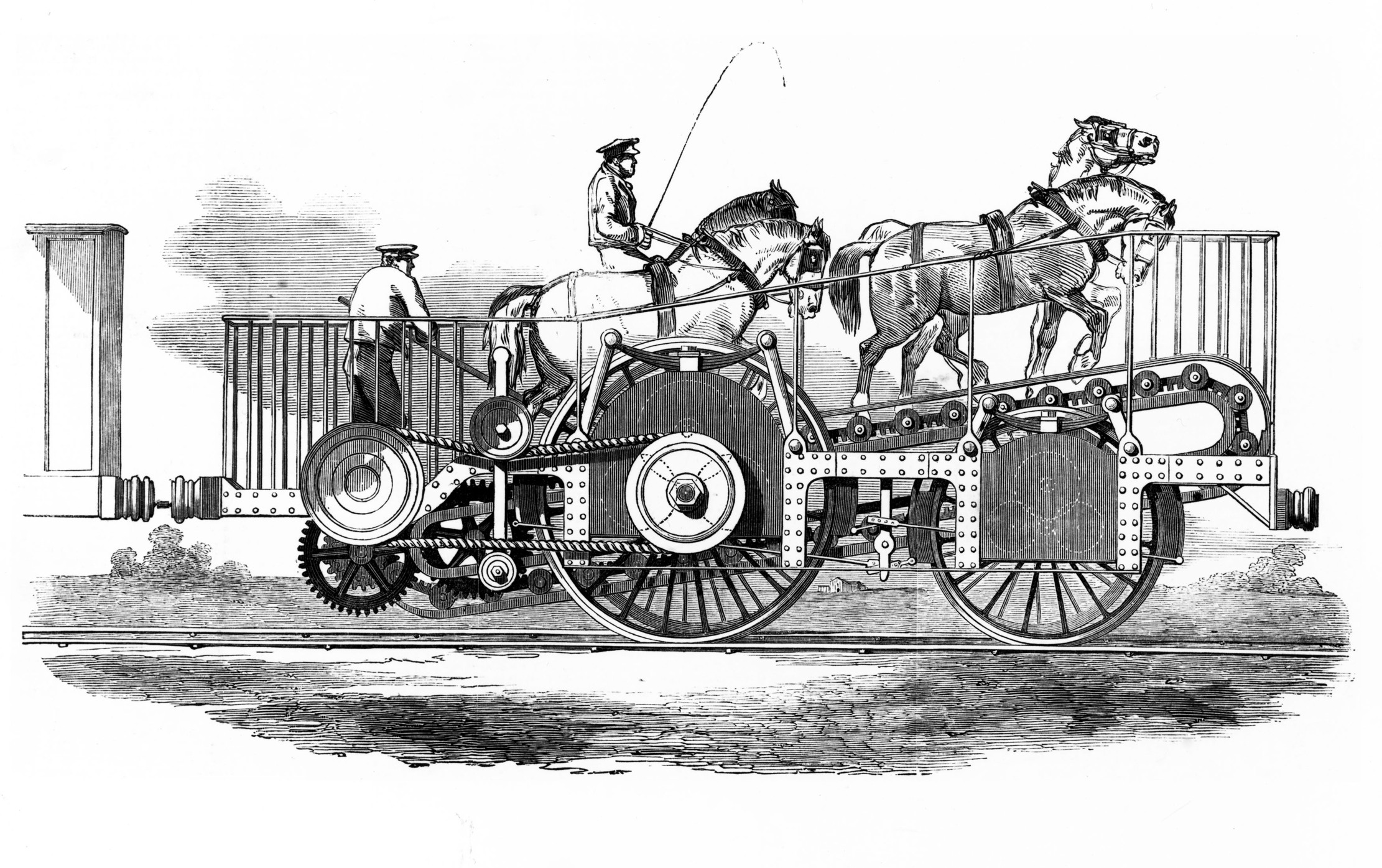

Curious questions: How a horse on a treadmill almost defeated a steam locomotive

Curious questions: How a horse on a treadmill almost defeated a steam locomotiveThe wonderful tale of Thomas Brandreth's Cycloped and the first steam-powered railway.

By Martin Fone

-

You've got peemail: Why dogs sniff each other's urine

You've got peemail: Why dogs sniff each other's urineEver wondered why your dog is so fond of sniffing another’s pee? 'The urine is the carrier service, the equivalent of Outlook or Gmail,' explains Laura Parker.

By Laura Parker

-

Curious Questions: Which person has spent the most time on TV?

Curious Questions: Which person has spent the most time on TV?Is it Elvis? Is it Queen Elizabeth II? Is it Gary Lineker? No, it's an eight-year-old girl called Carole and a terrifying clown. Here is the history of the BBC's Test Card F.

By Rob Crossan

-

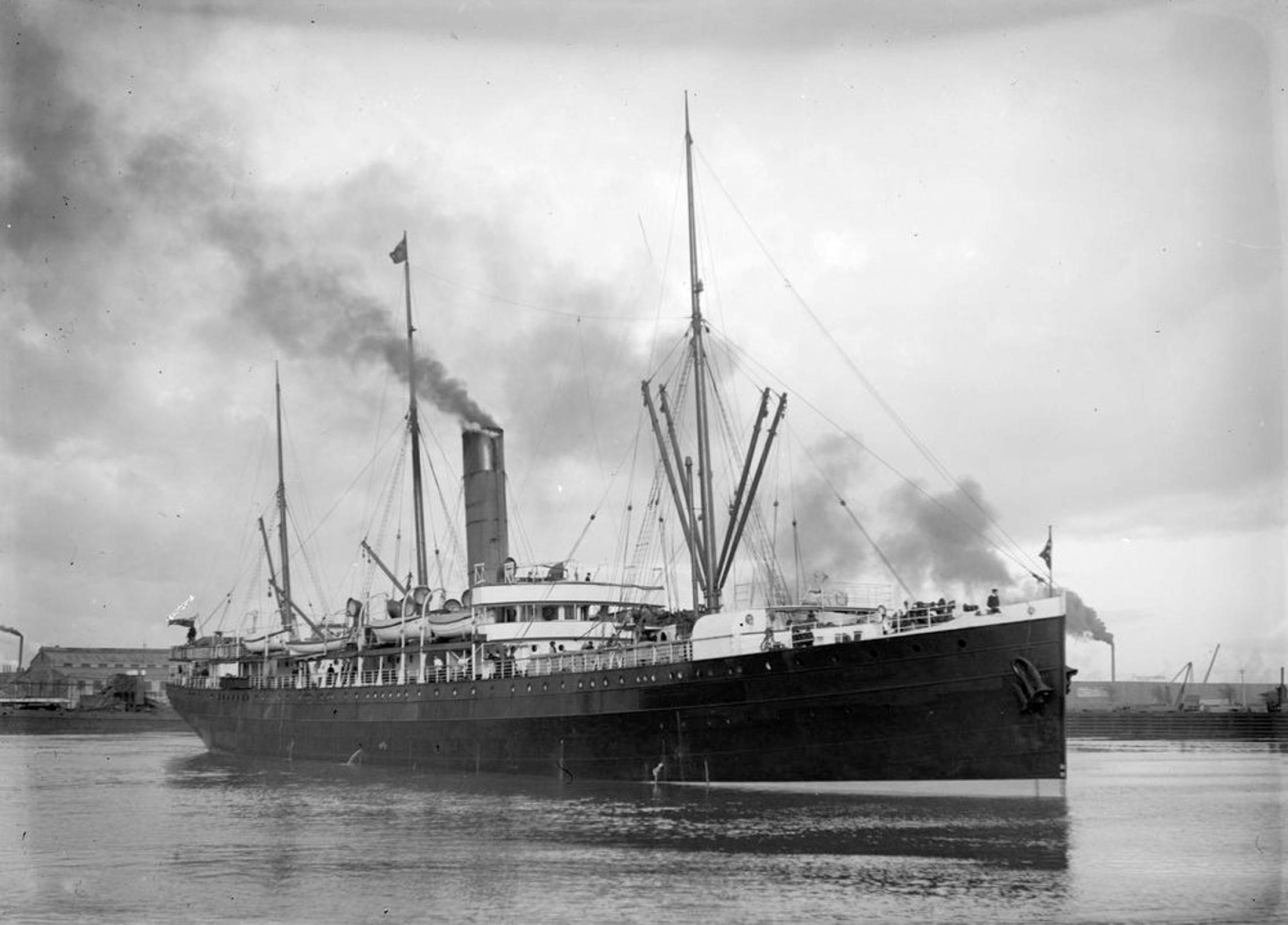

The ship that was in two different centuries, two different years, two different months, two different days and two different seasons, all at the same time

The ship that was in two different centuries, two different years, two different months, two different days and two different seasons, all at the same timeOn December 31, 1899, the SS Warrimoo may have travelled through time — but did it really happen?

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Was music's famous 'Lady of the Nightingales' nothing more than a hoaxer?

Curious Questions: Was music's famous 'Lady of the Nightingales' nothing more than a hoaxer?Beatrice Harrison, aka ‘The Lady of the Nightingales’, charmed King and country with her garden duets alongside the nightingales singing in a Surrey garden. One hundred years later, Julian Lloyd Webber examines whether her performances were fact or fiction.

By Julian Lloyd Webber

-

Curious Questions: Who wrote the Happy Birthday song?

Curious Questions: Who wrote the Happy Birthday song?There are few things less pleasurable than a tuneless public rendition of Happy Birthday To You, says Rob Crossan, a century after the little ditty came into being

By Rob Crossan

-

Why do we get so many April showers?

Why do we get so many April showers?It's the time of year when a torrential downpour can come and go in minutes — or drench one side of the street while leaving the other side dry. It's all to the good for growing, says Lia Leendertz as she takes a look at the weather of April.

By Lia Leendertz