Curious questions: How a horse on a treadmill almost defeated a steam locomotive

The wonderful tale of Thomas Brandreth's Cycloped and the first steam-powered railway.

The boom in the cotton industry in the north-west of England in the early 19th century quickly demonstrated the inadequacy of the existing infrastructure of canals and roads that were used to carry the raw materials required to feed the mills of Manchester and transport the finished goods to the port of Liverpool. To provide a more efficient solution, the Liverpool and Manchester Railway Company (L&MR) was founded on May 20, 1824, with its capital provided by 308 shareholders. The green light was given for the construction of the line when an Act of Parliament was passed in 1826, albeit at the second attempt.

A key decision facing the directors was the propulsion of the engines. Early forms of public railways had used animals, while the more recent Hetton Colliery Railway, designed by George Stephenson and opened in 1822, used a cable haulage system. Given public concern about the prospect of temperamental steam-belching leviathans racing through the countryside, the directors had wavered on the question as the Act went through Parliament. Once the bill was passed, they settled on an as yet unproven technology, the self-propelled locomotive.

To demonstrate that the technology was fit for purpose and to select between the various competing options, on April 25, 1829, the L&MR Treasurer, Henry Booth, issued a challenge to ‘all Engineers and Iron Founders’ and a prize of £500 over and above the cost price ‘for a Locomotive Engine, which shall be a decided improvement on any hitherto constructed’. The Trials, held on a specially constructed track in Rainhill, can be fairly described as the dawning of the railway age.

A number of rules were established to ensure fair play. The locomotive was required to pull a load three times its weight, the tender being included in the weight. If there was no tender and fuel was carried on the engine, there would be a proportionate reduction in the weight of the load. The engine, with carriages attached, would run up to the starting post and once its boiler pressure had reached 50PPSI, its journey would begin. Exact timings would be taken, including setting-up times.

Each engine was to make 10 trips of 1.75 miles each way, including one-eighth of a mile at each end of the line for getting up to speed and for stopping the train. In this way it would travel 35 miles, 30 of which would be at full speed, the equivalent of travelling from Liverpool to Manchester. A successful engine would have to demonstrate the ability to maintain a speed of at least 10mph. The exercise would then be repeated a further 10 times to simulate the return journey from Manchester to Liverpool.

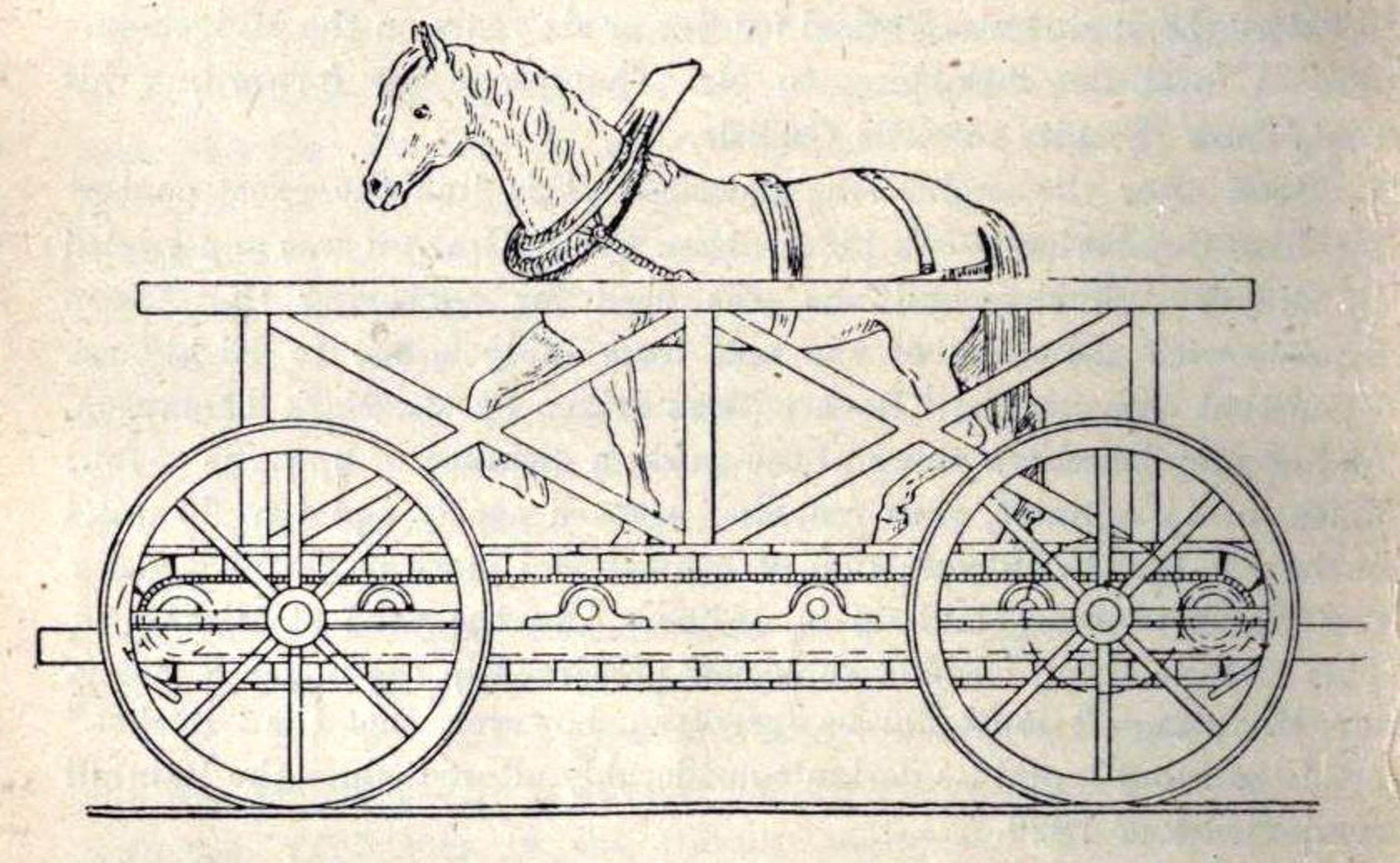

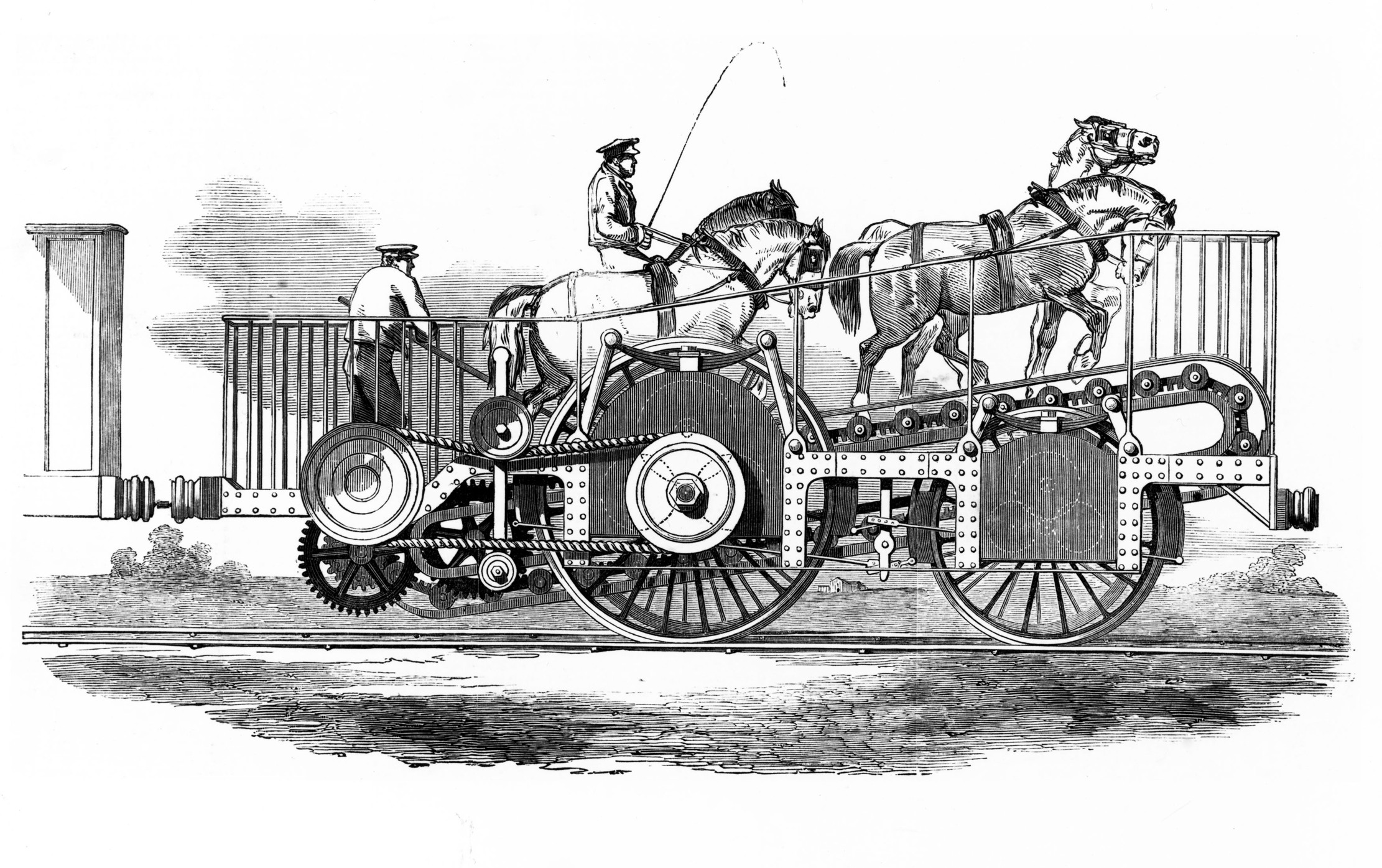

The Trials were held over nine days from October 6 to 14, 1829, and of the five entries that participated, one breached the no horses stipulation. Patented on September 9, 1829, (no 5840), Thomas Brandreth’s Cycloped was a flat-bed wagon propelled by a single horse attached to a treadmill. The animal’s kinetic energy was transferred to the drive wheels by a series of cogs. At the front there was a bucket, thoughtfully positioned to provide the straining horse with much needed refreshment.

Cycloped’s attempt to impress Brandreth’s fellow directors was ill-fated. Weighing around three tons complete with horse, it was too heavy for a single horse to produce enough energy to reach anything over a stately five miles per hour, way below the minimum required. It was also fragile, the horse eventually falling through the treadmill, damaging it beyond repair. What happened to the horse is not reported. The Brandreth family, though, were clearly proud of this curiosity as Admiral T Brandreth presented the Science Museum with a 1:6 scale model of Cycloped in 1894.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The trials caught the public imagination with around 10,000 assembling along the track to watch a battle royale between the contestants. There was something of a carnival atmosphere with brass bands serenading the onlookers. For the Times, though, it was the zenith of engineering progress with more ‘scientific gentlemen and practical engineers’ assembled in one spot than ever before.

Representing the hopes of the capital and the pre-trial favourite was Novelty, built by John Ericsson and John Braithwaite who had cut their engineering teeth building horse-drawn fire engines with steam pumps. With only seven weeks’ notice of the event, the engine used many of the same parts as their fire engines. Regarded as the first tank engine, what it lacked in drawing power it made up for in speed, reaching 28mph. However, its participation ended on October 10 when the bellows burst under steam pressure and it exploded.

John Hill and Timothy Burstall’s Perseverance incorporated a significant design feature that was to revolutionise railway design, using roller bearings for axles. However, the locomotive was damaged while being transported from Edinburgh to Liverpool and missed the first five days for repairs. Once in working order it was only able to reach speeds of 5–6mph, well below the required minimum, and so was withdrawn.

By contrast, even by the standards of the time the technology deployed by Timothy Hackworth, Superintendent of the Stockton and Darlington Railway, on Sans Pareil was antiquated. It had two particularly alarming features: its vertical cylinders gave the engine a strange rolling gait and the draft from the blastpipe was so strong that it shot most of the coke out unburnt. Despite a leaky boiler and other faults requiring constant running repairs, Sans Pareil did complete a few public trials before its participation was ended by a spectacular boiler explosion.

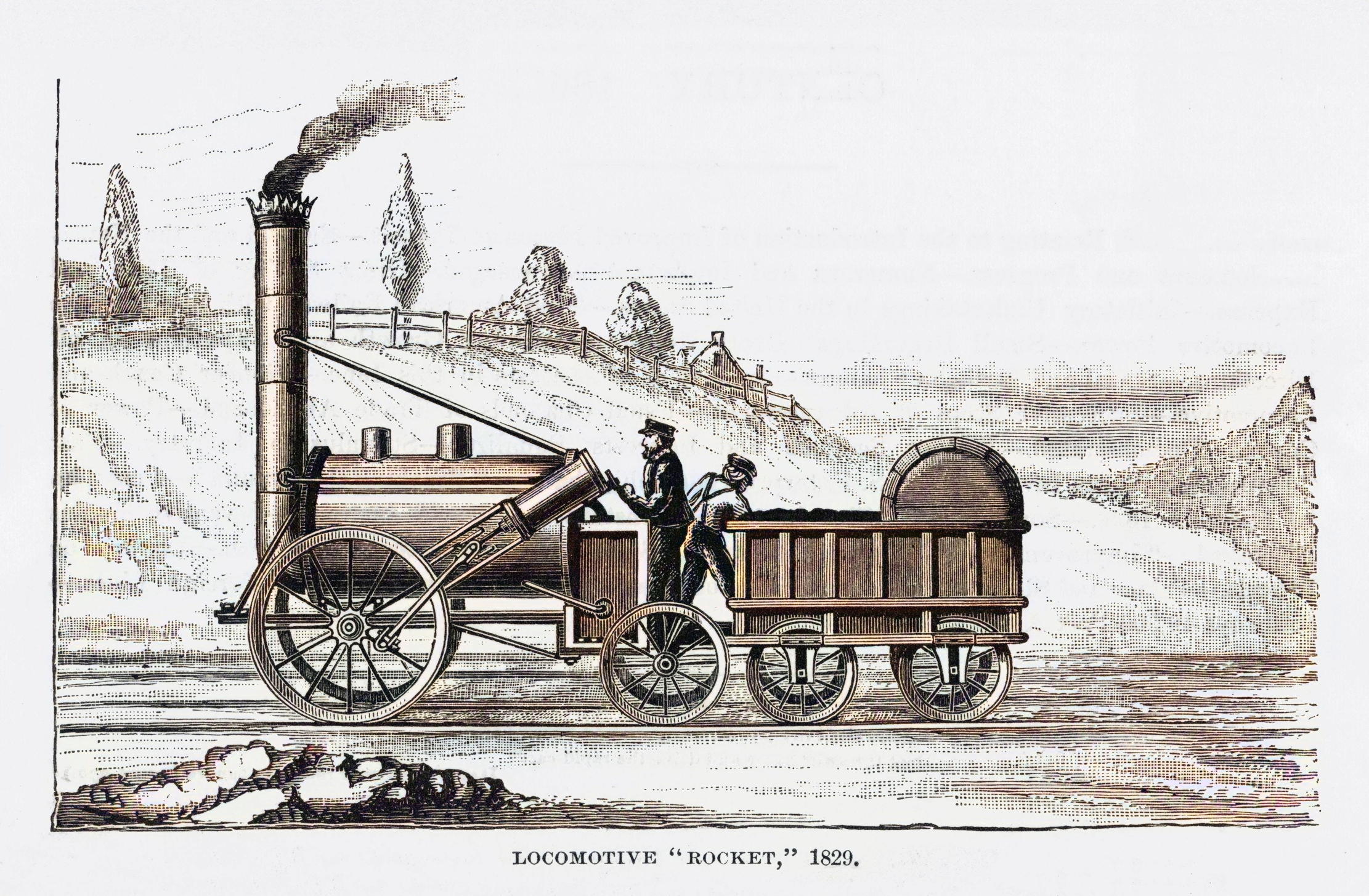

Entered by the L&MR’s Treasurer, Henry Booth, and its engineer, George Stephenson, and designed and built by Stephenson’s son, Robert, at his Forth Street Works in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Rocket was the most advanced locomotive of its day. Its single driver system gave it a considerable weight advantage over its rivals as coupling rods were not needed and the second axle was much lighter.

Stephenson’s Rocket’s finest moment came on the morning of October 8th when, drawing a full load of 13 tons including two wagons carrying stone, clocked a top speed of 29 miles per hour and averaged 12mph, prompting the Derby Mercury to wax lyrically that ‘it darted past the spectators’ with the ‘rapidity with which the swallow darts through the air’. To demonstrate its power it not only pulled the wagons, but pushed them back and forth.

This was enough to win the Stephensons the prize and the contract, although the L&MR also bought Sans Pareil, which they then leased to the Bolton and Leigh railway. The line between Liverpool and Manchester opened on September 15, 1830, the first railway to rely exclusively on steam-powered locomotives, to be entirely double-tracked throughout its length, to be fully timetabled, and to carry mail. The opening was marred by another notable first, when the Rt. Hon. William Huskisson, alighting from a train, was struck by the Rocket and fatally injured, the first widely reported railway casualty.

Since 2023 the original Rocket has been housed at Locomotion in Shildon, which is also home to a replica of Sans Pareil, built in 1980, and what remains of the original engine, the two pioneers that ushered in the railway age.

Martin Fone is the author of 'Fifty Curious Questions: Pabulum for the Enquiring Mind'

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.

-

Curious Questions: Why do golf balls have dimples? And why are tennis balls furry?

Curious Questions: Why do golf balls have dimples? And why are tennis balls furry?As the weather picks up, millions of us start thinking about dusting off our golf clubs and tennis rackets. And as he did so, Martin Fone got thinking: why aren't the balls we use for tennis and golf perfectly smooth?

By Martin Fone

-

You've got peemail: Why dogs sniff each other's urine

You've got peemail: Why dogs sniff each other's urineEver wondered why your dog is so fond of sniffing another’s pee? 'The urine is the carrier service, the equivalent of Outlook or Gmail,' explains Laura Parker.

By Laura Parker

-

Curious Questions: Which person has spent the most time on TV?

Curious Questions: Which person has spent the most time on TV?Is it Elvis? Is it Queen Elizabeth II? Is it Gary Lineker? No, it's an eight-year-old girl called Carole and a terrifying clown. Here is the history of the BBC's Test Card F.

By Rob Crossan

-

The ship that was in two different centuries, two different years, two different months, two different days and two different seasons, all at the same time

The ship that was in two different centuries, two different years, two different months, two different days and two different seasons, all at the same timeOn December 31, 1899, the SS Warrimoo may have travelled through time — but did it really happen?

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Was music's famous 'Lady of the Nightingales' nothing more than a hoaxer?

Curious Questions: Was music's famous 'Lady of the Nightingales' nothing more than a hoaxer?Beatrice Harrison, aka ‘The Lady of the Nightingales’, charmed King and country with her garden duets alongside the nightingales singing in a Surrey garden. One hundred years later, Julian Lloyd Webber examines whether her performances were fact or fiction.

By Julian Lloyd Webber

-

Curious Questions: Who wrote the Happy Birthday song?

Curious Questions: Who wrote the Happy Birthday song?There are few things less pleasurable than a tuneless public rendition of Happy Birthday To You, says Rob Crossan, a century after the little ditty came into being

By Rob Crossan

-

Why do we get so many April showers?

Why do we get so many April showers?It's the time of year when a torrential downpour can come and go in minutes — or drench one side of the street while leaving the other side dry. It's all to the good for growing, says Lia Leendertz as she takes a look at the weather of April.

By Lia Leendertz

-

Who was the original Jack Russell who gave his name to one of Britain's favourite dog breeds?

Who was the original Jack Russell who gave his name to one of Britain's favourite dog breeds?Kate Green takes a look at the the legacy of Revd John Russell, the man who gave his name to the Jack Russell and Parson Russell terriers.

By Kate Green