Curious Questions: Did the Tower of London menagerie provide the animals for London Zoo?

Wolves in the Tower of London and an elephant so well trained that Lord Byron wanted to adopt it as his butler — Martin Fone discovers the strange and terrifying history of the last of London's menageries, and how they helped establish what we'd recognise today as its first zoos.

Founded in April 1826, the Zoological Society of London brought to fruition the dream of Sir Stamford Raffles, Humphry Davy, and Joseph Banks, to create a zoological collection that would not only ‘interest and amuse the public’ but also rival that of the Jardin des Plantes in Paris. A plot of land was purchased from the Crown in Regent’s Park, animal houses were constructed, and on April 27, 1828, what is now ZSL London Zoo opened its doors to the society’s members. It is the world’s oldest scientific zoo, but, curiously, the public was only allowed entry in 1847, their ticket money a welcome boost to the Society’s depleted funds.

For centuries keeping exotic animals, often given as diplomatic gifts, was the preserve of royalty. In 1110 King Henry I built a seven-mile-long wall at the Royal Park of Woodstock in Oxfordshire to enclose a collection of lions, camels, and porcupines, possibly England’s first zoo. The animals were kept not to satisfy any scientific interest, but to add some spice to the king’s passion for hunting.

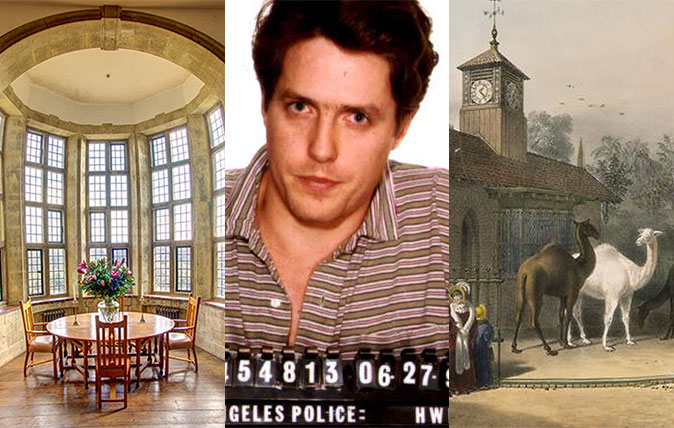

A gift of three lions from the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick II, in 1235, led to Henry III creating his own menagerie, which included a polar bear, allowed to fish in the Thames, and, in 1255, an animal which the contemporary chronicler, Matthew Paris, described as ‘a rough-hided animal that eats and drinks with its trunk’. By the 1270s Edward I had built the Lion Tower, at the entrance to the Tower of London, to house the growing menagerie.

Keeping elephants was problematic as the assumption was that they were carnivores, while, in 1623, James I was advised to feed his on a diet of wine between the months of September and April. This woeful ignorance of their dietary requirements, together with cramped living conditions and the extremes of the English climate, meant that most animals were condemned to short, miserable lives.

The public first gained access to the menagerie during the reign of Elizabeth I. Admission was free if they were accompanied by cats or dogs, which were collected and fed to the carnivores. Visitors were advised ‘not to approach too near the dens and avoid every attempt to play with’ the animals, sensible advice that was not always heeded. On February 8, 1686, Mary Jenkinson was savaged to death after patting a lion’s paw.

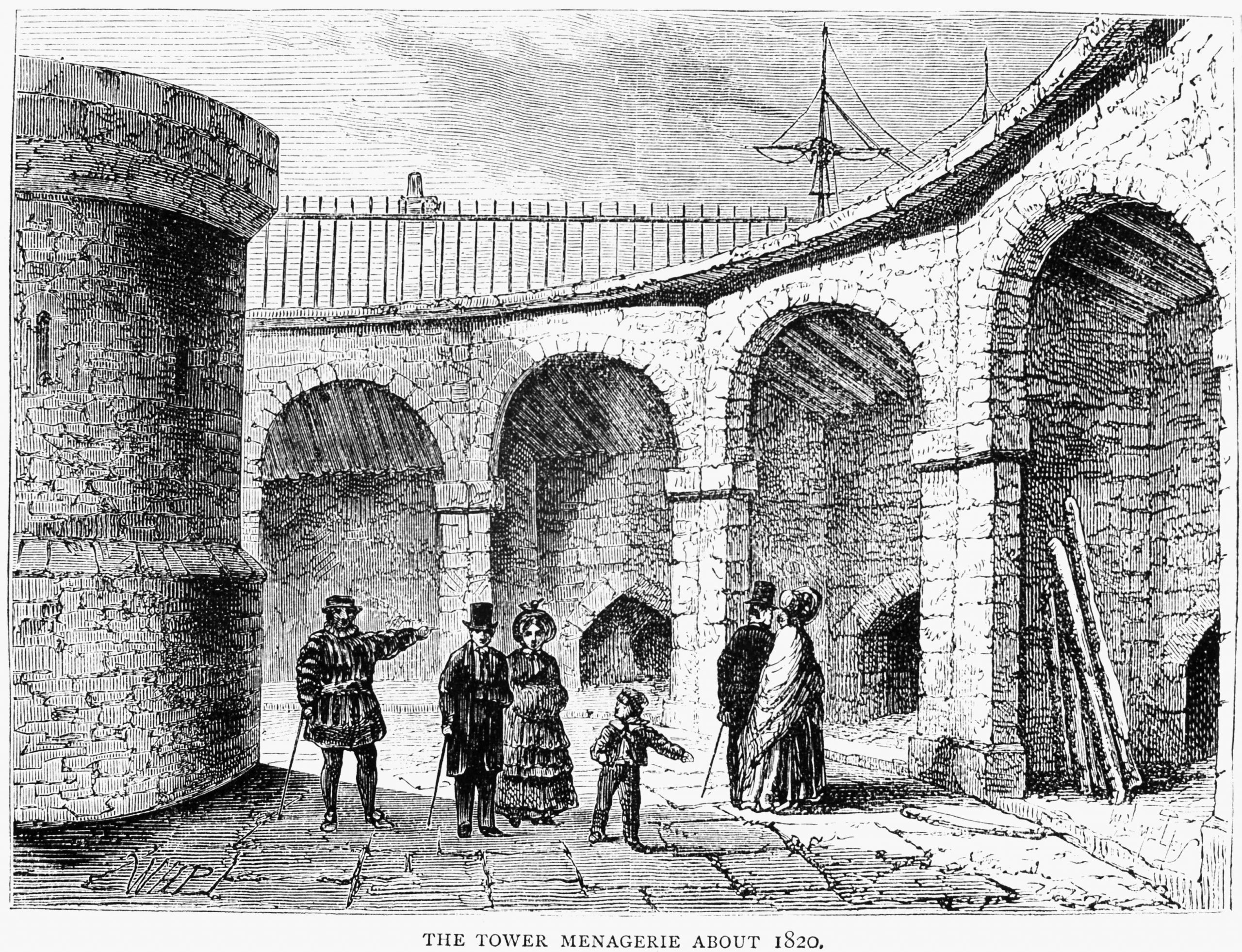

When Alfred Cops was appointed head keeper in 1822 all that was left of the collection was a handful of animals, but within six years he had built up the stock to some 300 animals, representing sixty species, and improved their living conditions. A successful breeding programme led one commentator to observe that ‘those whelped in the Tower are more fierce than such as are taken wild’.

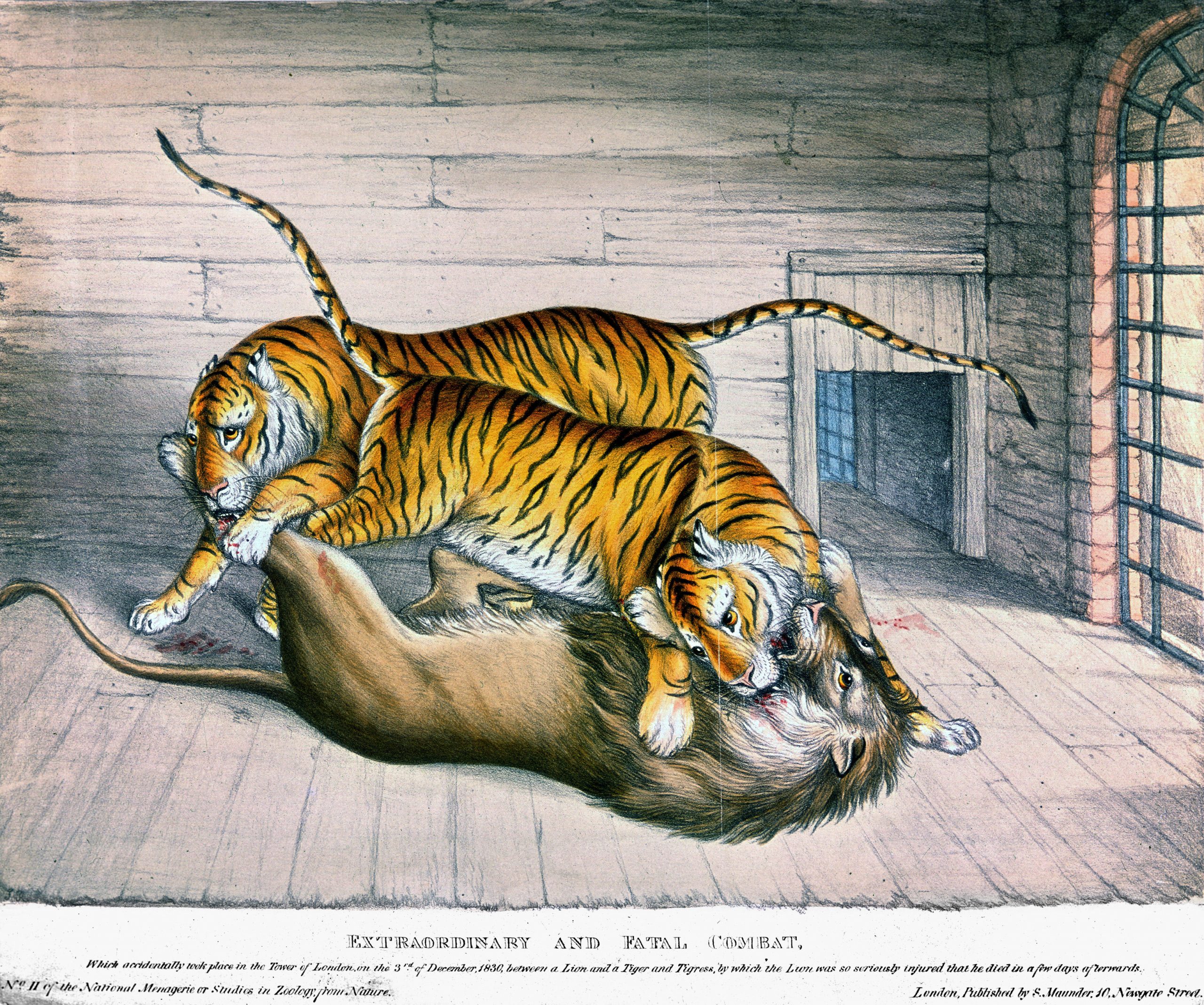

Despite Cops’ success, accidents and escapes dogged the menagerie. Wolves broke into a keeper’s apartment, causing his wife and children to flee for their lives, a secretary bird inadvisably poked its head into a hyena’s enclosure, and a battle royal between two tigers and a lion, accidentally let into the same cage, resulted in the lion’s death. With the new zoo at Regent’s Park offering alternative accommodation, the government, tiring of the problems associated with the menagerie, transferred many of the animals there.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Cops, though, was allowed to exhibit his own animals there, but even then, misfortune followed him, leading authorities to close the menagerie down after an audacious attack by a monkey on a guardsman. On August 28, 1835, the public were admitted for the last time. Shortly afterwards, the remaining animals were sold to an American showman, Benjamin Franklin Brown, and the Lion Tower was demolished.

Cops was not the only entrepreneur to pander to the public’s desire to see exotic animals. London’s most bizarre menagerie was founded by the Pidcock family in 1773 on the rickety upper floor of Essex Exchange, on the northern side of the Strand, initially as the winter quarters for the animals in their travelling circus. It soon became a popular tourist attraction.

The room was decorated with exotically painted scenery and caged dens housed the animals, which included lions, tigers, jaguars, tapirs, and, to test the strength of the floorboards to their maximum, several pachyderms. Higher up the walls were enclosures for birds and monkeys. The roars of the animals could be heard in the Strand, often startling the passing horses.

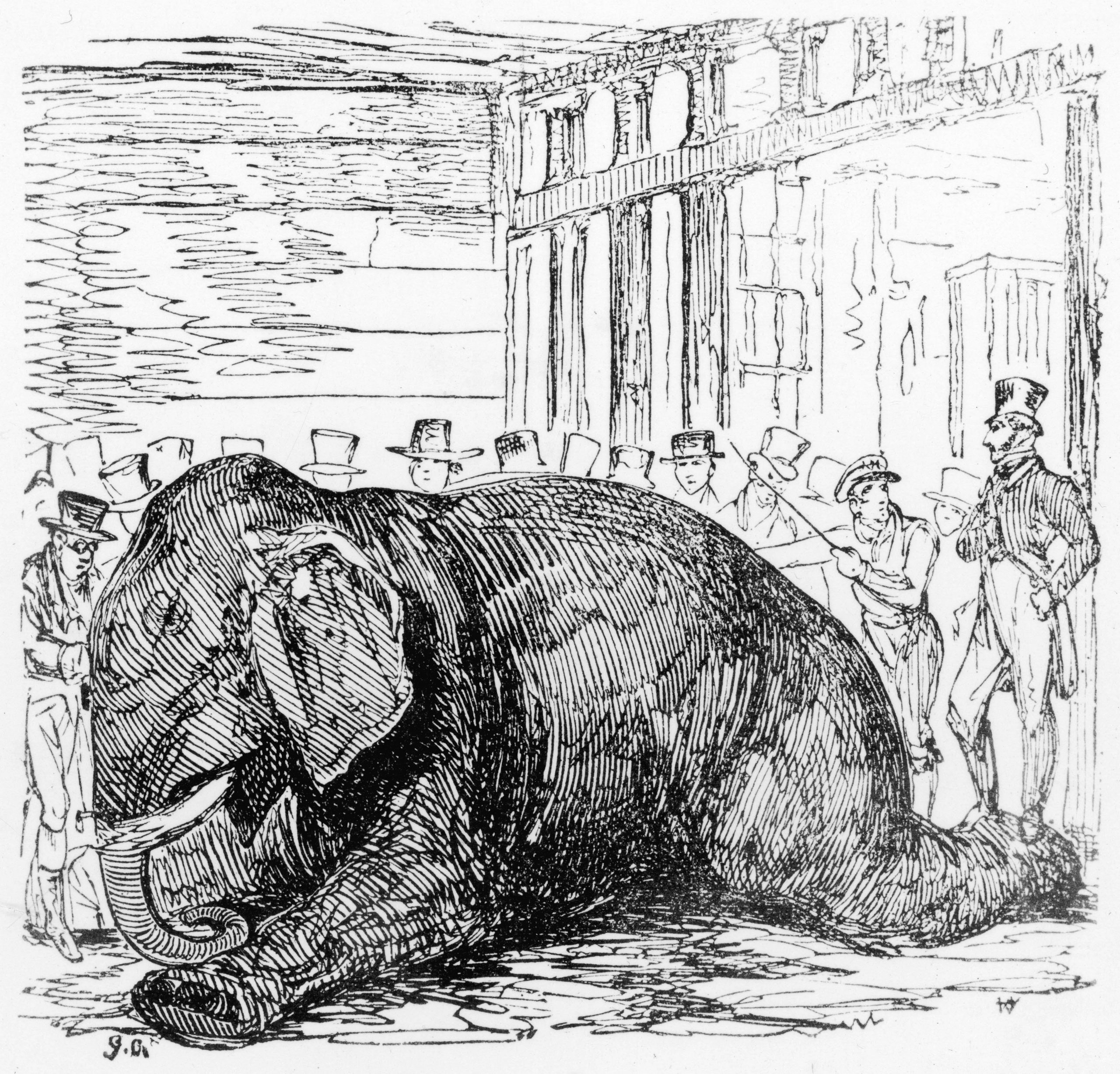

Edward Landseer painted some of the animals while Lord Byron was charmed by the menagerie’s elephant, Chunee. It ‘took and gave me my money again’, he noted in his diary for November 14, 1813, ‘took off my hat – opened a door – trunked a whip – and behaved so well, that I wish he was my butler’. While the panther, he opined, was the ‘handsomest animal on earth’, the ‘poor antelopes were dead’.

Renamed the Royal Grand National Menagerie when Edward Cross acquired it in 1814, guests were greeted by a doorman dressed as a Yeoman of the Guard, a clear nod to the rival establishment at the Tower. Chunee, the star attraction, took up residency in 1809, regularly parading in the streets and appearing on the stage, completing a forty-night stint at the Theatre Royal, Haymarket.

Sadly, on February 26, 1826, it all proved too much, and Chunee attacked and killed his keeper. It took three days, a civilian firing squad, soldiers from Somerset House, a small cannon and 152 balls of ammunition to put him out of his misery.

Chunee’s demise led to public outrage, attendances plummeted, and, to add to Cross’ woes, as part of the redevelopment of the Strand, Essex Exchange was demolished in 1829. He moved his menagerie to King’s Mews, now the site of the National Gallery, before selling some animals to London Zoo.

So some did become part of London Zoo's collection, but not all. The remaining animals were sold in 1831 for £3,500 to the Surrey Literary, Scientific, and Zoological Society, which Cross himself had founded.

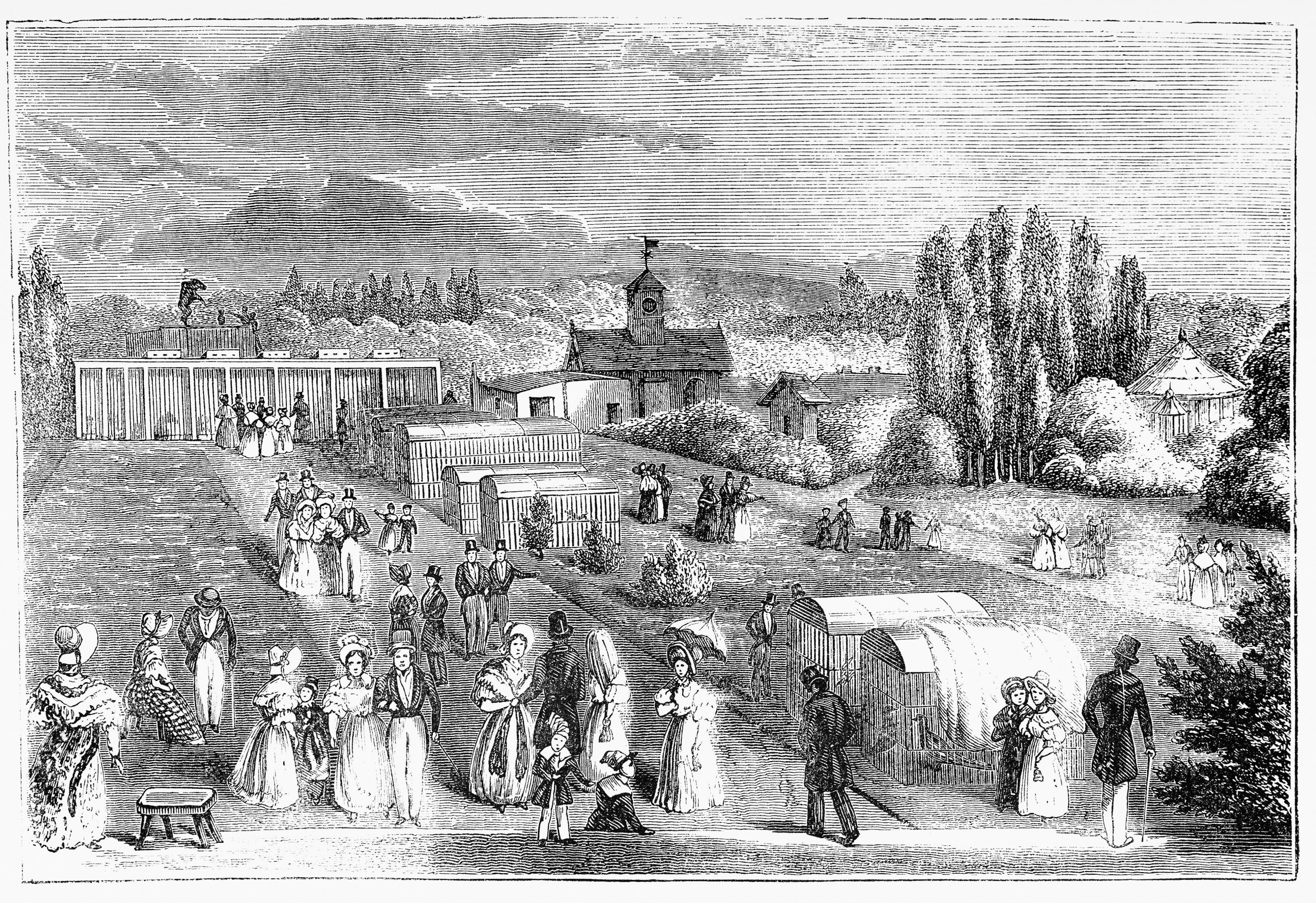

Under his direction, the Society established Surrey Gardens on eighteen acres of parkland in Walworth. It boasted promenades, spectacular gardens, laid out by Henry Phillips, firework displays, balloon rides, and historical re-enactments, including the eruption of Vesuvius and the Great Fire of London.

At its height upwards of 8,000 people attended a day, happy to pay their shilling admission. Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, and their children visited in 1848.

The principal attraction, though, was its zoo, which in its pomp was home to 170 species. At its centre was a large, circular, domed, glass conservatory, a precursor to the Crystal Palace, in which exotic fish, birds, and animals were displayed. Feeding time was a particular draw, and the keepers were not averse to teasing the animals to guarantee ‘a good show’.

It was also the home to five giraffes, the first to be publicly displayed in Britain, which were transported from Africa in 1843 and walked from the docks to Walworth at night so that residents were not disturbed by ‘these strange horses’.

Cross’ death in 1854 hastened the Garden’s end. The animals were sold off in 1855 to fund a 12,000-seater music hall which burnt down six years later, and property developers bought the park in 1877. The ghostly cries of the animals, it is said, can still be heard today.

The penguins of London Zoo: Traditionally good parents, occasionally clumsy and strictly not monogamous

'Once, the BBC was filming here and the penguins would take apart the equipment and run away with it, always

The tale of how London Zoo survived and thrived through lockdown

ZSL London Zoo is open to the public once again. Eleanor Doughty was first in through the gates to greet

50 things Britain gave the world, from apologies to zoos

Throughout the centuries, Britain has led the world in all that is civilised, from culture to condiments and fast horses

Credit: Gett

Curious Question: Do goldfish really have a three-second memory?

Martin Fone wonders whether everyone's favourite pet fish has greater cognitive abilities than we give it credit for.

The slithering truth about the snakes of Britain, from grass snakes to the 6ft beasts that roam central London (yes, really)

Forever associated with sin, these elongated reptiles are much misunderstood contributors to our ecosystem, believes Annemarie Munro.

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.