Crofting in the 21st century: The passionate, hardy farmers still working the ancient lands of the Highlands

Remote working has a whole other meaning for those passionate individuals still farming crofts in the Highlands. Joe Gibbs takes a look and discovers crofting to be alive and well — though still as tough a life as it ever was.

The tiny west Highland township of Elphin, north of Ullapool, stands out from the moorland landscape as a patchwork of bright green. Its rare fertility derives from a seam of limestone beneath the soil. Rank heath surrounds it as far as the eye can see and beyond that lie slabs of Lewisian gneiss, the oldest rocks in Europe, three billion years old. Home to about 60 souls, many of them crofting families, Elphin straddles the A835, until recently a road unremarkable for much other than the lonely beauty of the hills either side and the fish lorries from Lochinver that thunder southwards late at night.

In 2014, the road’s fortunes changed. A group of Highland businessmen conceived the North Coast 500, a looped tourist route that travels most of the coastal Highlands, passing Elphin and other crofting communities. Essentially a marketing exercise, NC500 has been an extraordinary success, repackaging a 516-mile circuit of existing tarmac into a version of Route 66 in the US.

"Times have changed for the better, but crofting is still a struggle"

Traffic and visitors have increased yearly. Some locals complain of bumper-to-bumper Porsches blocking the 200 miles of potholed single-track roads and the antics of campervan drivers who can’t reverse without sliding into a ditch. For contributors to the Facebook page ‘NC500 The Land Weeps’, the route has become a curse. For many others, however, it’s a commercial lifesaver.

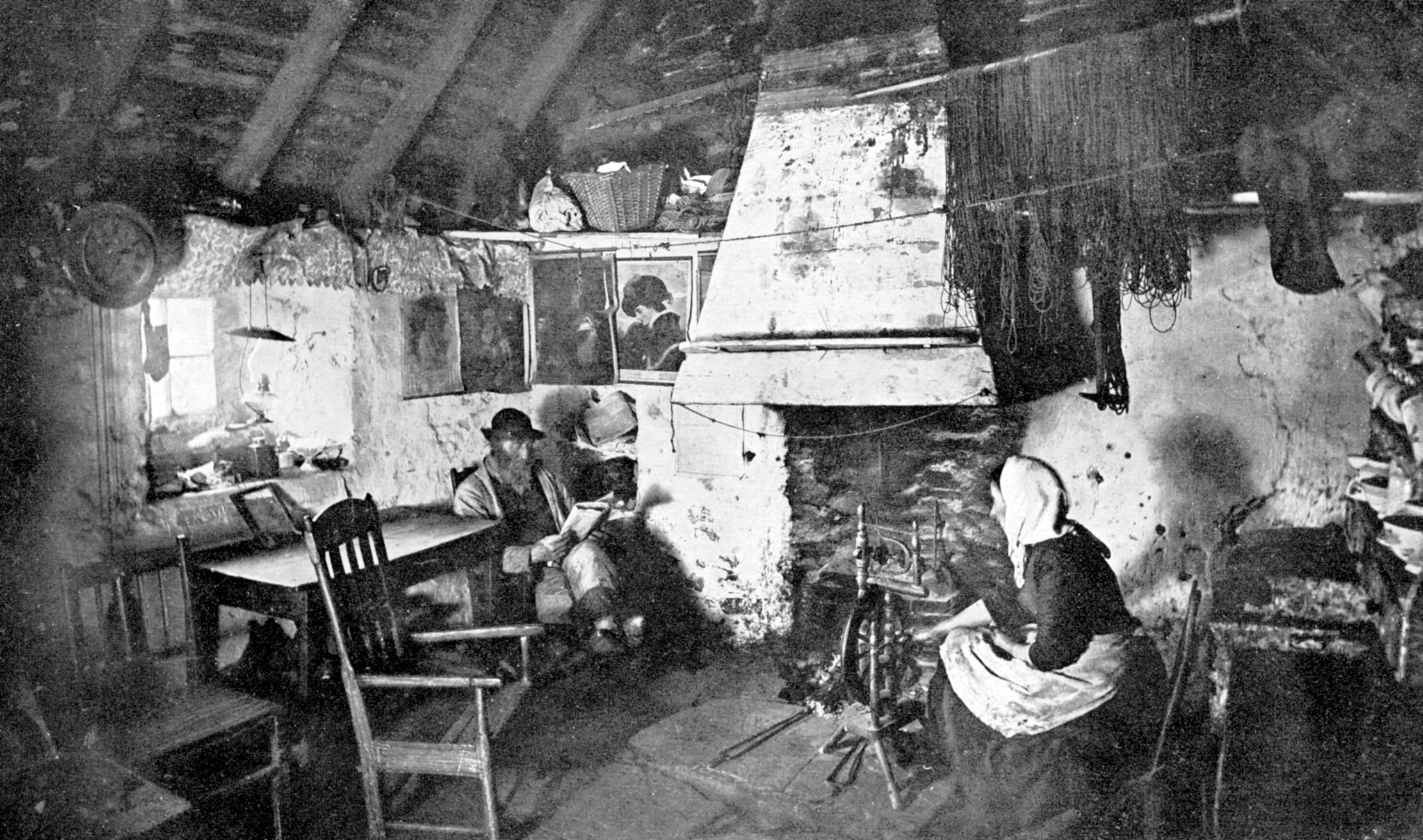

As visitors traverse the rugged landscape, in many places, they can see the pretty little stone cottages and regular field patterns of crofts, a form of landholding unique to the Highlands and Islands. If they look hard, they may discern, behind the beauty, that the terrain is a palimpsest of centuries of struggle to scratch sustenance from an unforgiving environment. A low sun shadows the ridges and furrows of past runrig and lazy-bed cultivation, the last a misleading name for a back-breaking form of tillage. Piles of stones show where there was once a rude black house, a damp rubble dwelling with no windows or chimney, a thatched straw roof and trampled mud floor, where family and cattle shared the same living space.

Visiting Skye in 1877, a correspondent to The Scotsman noted, emerging from an almost ruinous cottage, children that were ‘puny, uncombed, blear-eyed, shivering little objects… This sorrowful index to the condition of the crofter forces itself very strongly on a stranger’s notice’.

Times have changed for the better, but crofting is still a struggle. For Helen O’Keefe, a crofter in Elphin, NC500 probably makes the difference between surviving there and not. Crofts were never conceived as more than homes and subsistence farms. Their average 10 acres, always leased from a landlord in the past, indicate that the creators assumed a crofter would have a daytime job. For Miss O’Keefe, the roadside Elphin Tea Rooms and shop she bought with her eight-acre croft, open all week in summer, provides a vital additional income, much of it from the flow of tourists. Nonetheless, it is not what she came there for; the croft is her passion.

The judges who appointed Miss O’Keefe 2021 ‘Young Crofter of the Year’ dubbed her a human dynamo. It’s no exaggeration. A former mining engineer and elite rower, brought up on a hobby farm in south-west Australia, she visited the west Highlands on holiday and fell in love with the place and with her Irish partner Brendan, an ecologist, who lived in Elphin. When the croft and cafe came up for sale, she persuaded her mother, Ann, now 70, to sell up and join her in the venture.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Five years on, Miss O’Keefe is running a flock of 100 mostly Shetland sheep on the croft’s inbye fields and on the 2,500 acres of common grazings she shares with the five other active crofts in the township. She hand-clips the sheep herself and sends the light grey wool away to be spun into yarn, which is sold to knitters through her shop. It’s impossible to match commercial prices for wool, but there are niche buyers who are prepared to pay more for the traceability and the story. Some of the best fleeces are sold for felting.

Lambs are slaughtered for meat in Dingwall and Miss O’Keefe butchers the carcasses herself in a hired facility nearby. She freezes the meat and sells it directly to customers in lamb boxes or individual cuts. On gathering days, she and her fellow crofters work together to bring the sheep off the hill into the village fank (or sheepfold). At the end of the day, they share a dram and a blether. Such days are important in holding the township together.

Next to the croft house, Miss O’Keefe tends a vegetable garden, produce from which feeds the family and supplies the cafe. She has planted an orchard and applied for a grant to build a polytunnel. Her hens, she hopes, will allow her to develop an egg business. Her hay she scythes and rakes by hand, helped by another family, although a neighbour recently bought a tractor — the first in the township for some time — which will assist with cutting and muck spreading. Farm machinery is shared by the crofters. Somehow, she even finds time to be grazings clerk (administrator) for the township and to run an online shop for local produce with a neighbour, collecting meat, eggs, home-baked bread, scones and cakes, vegetables and garlic, all of which are delivered to Ullapool, 15 miles south.

The biodiversity of Miss O’Keefe’s croft and its locality are important to her: the wildflowers, including orchids, that thrive on the non-intensive grazing; the impetus the patchwork nature of the fields gives to wildlife — to waders such as golden plover, snipe, oystercatchers and lapwing that like stock-poached ground; and the peatlands, a huge carbon store. Her dream is to create the perfect field for corncrake, a heavily threatened species. ‘It’s really important that crofting is taken seriously as agricultural food production for the country,’ she insists. ‘It provides very low-input, environmentally friendly meat and, done well, it maintains habitat and biodiversity.’

Of today’s 21,186 registered crofts spread over the five Highland crofting counties, 1,127 are uninhabited or unworked. Yet despite a constant stream of people enthusiastic to continue the way of life, many of them young families, most potential crofters find it very difficult to get a croft. The heavily protected nature of the tenancies complicates unworked land being redistributed by the Crofting Commission, the regulatory body. As the saying goes, a croft is a small piece of land surrounded by legislation, a situation that has evolved through a history of crofters needing protection from landlords, but now proves to be the undoing of some aspirants.

Unused crofts are a source of frustration both to Scottish Crofting Federation chief executive Patrick Krause and to Murray MacLeod, a crofter and commentator in Swainbost on Lewis. Both acknowledge that their raison d’être is to keep people on the land and rural communities alive — and both rue the amount of land lying fallow. Blame rests on a 1961 act that allowed crofts to be assigned to persons outside the immediate family, thus making them tradeable.

In Elphin, 115 separate crofts have been amalgamated into 10 parcels, of which six are actively worked. If crofters don’t live on their ground, in theory, they must be no more than 20 miles away. A croft is meant to be cultivated and maintained, but it has been hard for an under-resourced Crofting Commission to track down owners of neglected ones and to check the accuracy of annual reports on purposeful use, the definition of which is loose. As Mr MacLeod says: ‘Growing a wee square of potatoes could be purposeful use.’

Yet things are looking up. Mr Krause has started an index matching would-be crofters with ones he hears are coming vacant and hopes for reforming legislation in the next Scottish parliament. The Crofting Commission has new funding to locate and persuade owners of unworked crofts to revive them, either themselves or via new ownership. All being well, a visitor returning to Elphin on the NC500 in a few years will notice more lights in the glen and more work in the fields.

Bothies: The hidden shacks across Britain offering shelter, comfort and warmth to weary travellers

Once frequented by farm labourers and shepherds, lone bothies — often located amid some of Scotland’s most remote countryside —

Credit: Galbraith

An estate full of mountains, lakes and rivers where Robert the Bruce once fled his enemies

The Glenlochay estate in Perthshire contains thousands of acres of unspoilt Highland countryside, a handsome farmhouse and three of the