Come on in, the water’s lovely: Why we all love a lido

Britain’s historic outdoor swimming pools, long neglected, are back in business.

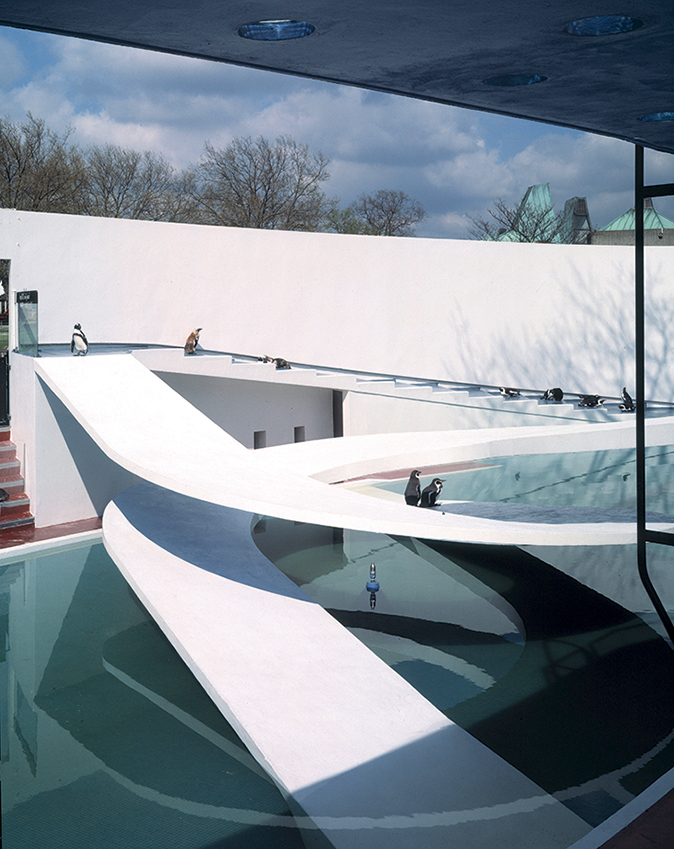

The London Zoo penguins didn’t know they were born. For 70 years, they splashed around in one of the most extraordinary open-air swimming environments ever created. The Lubetkin Penguin Pool, which opened in 1934, was an ocean-liner run gloriously aground in Regent’s Park. Its flippered residents sun-bathed on swoops of reinforced concrete leading into the water and posed grandly by the columns like Romans in the Senate. It was a Modernist symphony in blue and white—and a lido in all but name.

All over the country, people were doing much the same. The gleaming municipal pools that are synonymous with 1930s elegance brought the holiday mood to Britain. Workers had finally won the right to paid leave and they wanted somewhere to spend it. Lidos were for larking about in and falling in love around as well as swimming and you left your cares behind as you passed through the turnstiles. They were places to be seen; you dressed up to get undressed. The London Zoo pool’s designer, Georgian-born émigré Berthold Lubetkin, was channelling all of this—and the penguins seemed to hold their beaks a little higher as they strutted around their new home.

Everyone knows what happened next. Package holidays, patchy weather and a pursuit of novelty in all things combined to put lidos in the shade. Leisure centres took over and, of the 169 lidos built during the 1930s, only 31 were still open to swimmers in 2016. However, the tide is turning.

More than a dozen lidos have been restored or reopened in the past few years, from Penzance’s tidal Jubilee Bathing Pool (which turned the town into the Saint-Tropez of the South-West when it opened in 1935) to Gourock Outdoor Pool in Renfrewshire, overlooking the Clyde Estuary. Tooting Bec Lido, which dodged the axe in the 1990s, is now a training ground for swimmers attempting a Channel crossing: after fewer than 20 lengths you’ve done a mile. However, what’s made us fall back in love with them?

‘For me, the magic lies in the combination of the lido’s obvious physical charms—the peace, the views, the clear water, the year-round swimming—and the sense of community,’ explains Alexandra Heminsley, author of Leap In (£12.99, Hutchinson), a memoir of becoming an open-air swimmer. ‘In the UK, most of the lidos still in action are there because of the people who swim in them: they care about them and they care about each other. What they don’t care about is what you wear, how fast you are or whether you look “right”.’

Her favourite is Pells Pool in Lewes, East Sussex, a 150ft spring-fed oasis overlooked by Corsican pines. Not strictly a lido (it was built in 1860), spiritually, it’s still very much under the municipal-baths umbrella. ‘After a winter of harsh salty seawater or chlorinated captivity, the water of spring- time at the Pells tastes like actual heaven. It’s as far from the mood of swimming in the sea as it’s possible to be, but every bit as joyous.’

Pells is one of the lucky ones: it’s never closed. The waters have been considerably choppier for nearby Saltdean Lido, Britain’s only Grade II*-listed coastal lido. In its heyday, it looked like a film set, complete with a man-made beach (featuring ‘real seashore sand’), speakers that played big-band tunes to bathers and a Hollywood-style soda fountain. After decades of slow decline, it closed in 1994 and the site’s then owner announced it was going to be turned into flats in 2010. However, he didn’t bargain on the Save Saltdean Lido Campaign, whose members fought first to save it from conversion, then for funding—and, on May 27, the pool welcomed its first swimmers in 20 years.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

One of them was Rebecca Crook, who’s been involved from the start. ‘When the water was turned on, it was incredibly exciting,’ she tells me. ‘We’re probably getting about 30 emails a day about it, from people who learned to swim there and now want to bring their own children and grandchildren. We had somebody the other week getting in touch from Australia. She’d met her husband there when he was a lifeguard in the 1960s. It’s an iconic building and our vision was to get it back to how it was in the 1930s, but lidos aren’t museums: they’re heritage you can really interact with.’

The new, improved Saltdean’s waters are now heated for the first time and swimmers are able to make the most of its sun terraces and rotunda windows via a pop-up cafe. All of this, of course, comes at a cost—as do planning applications and legal challenges. ‘The reality of these projects is that you need hard cash,’ laments Miss Crook.

For the lidos whose future hangs in the balance (Peckham’s in south London and West Yorkshire’s Otley Lido, to name just two), Saltdean is an inspiration. Another is Cleveland Pools. Standing on Bath’s smallest crescent, the country’s only surviving Georgian pool is on course to welcome its first bathers since 1984 next year, having spent the past 30 years as a trout farm serving cream teas.

‘I’ve always been enthralled by the romanticism of it,’ enthuses Sally Helvey, an independent tour guide and Cleveland campaigner. Like many lido-lovers, she traces her devotion back to childhood. ‘My grandmother lived in Bathwick and, in the 1960s, we’d walk down the hill onto the canal to get to the pool. You could hear the squeals of delight from the children who were already there and that sense of anticipation was absolutely wonderful. I can clearly remember the feeling of getting into the cold water on a hot day and coming out with goosebumps, then the sun on my skin and the starched towels. It just felt so much healthier and more exciting than swimming indoors.’

Thanks to its history (peopled with colourful sorts; its Victorian proprietor, Capt Evans, kept bathers in line with a pet baboon) and potential for community use, Cleveland secured backing for redevelopment from the Heritage Lottery Fund in 2014. The waters in the new incarnation will be heated for the first time in 200 years and the focus will be on year-round use. ‘If you’re training for a triathlon, it’ll be great,’ advocates Mrs Helvey. ‘And, even if people don’t want to swim, they can do water-polo practice or pilot radio-controlled boats around.’

And the London Zoo penguins? They were moved in 2011 to a new site called Penguin Beach, which is unlikely to trouble RIBA. Lubetkin’s Grade I-listed pool is still in situ, complete with its original Hockney-blue-tiled floor, so, with the lido renaissance in full swing, perhaps it’s time for a refill?

Open-air pools to dive into this summer

Tinside Lido, Plymouth A dip here feels like swimming in a gigantic fountain. Right at the tip of Plymouth Hoe, Tinside’s once-derelict semi-circular lido was brought back to life in 2015. Open from late May until mid September (01752 261915)

Chagford Pool, Dartmoor Solar-heated, minimally chlorinated and fed by the River Teign, Chagford really sparkles. After your swim, pick up a lemonade from the tea shed and dry off on the grass. Open from late May until mid September (www.chagfordpool.co.uk; 01647 432929)

Bude Sea Pool, Cornwall The closest you can get to swimming in the sea without actually being in it. Bude’s magnificent tidal pool is carved out of the rocks on Summerleaze Beach and topped up by the Atlantic. It’s open and free to use 24 hours a day, all year round, although bathers are strongly encouraged to get their laps in at low tide (www.budeseapool.org)

Keep your diary up-to-date with our selection of unmissable events and things to do in the next few weeks.

The best restaurants in London

Rosie Paterson finds the 71 best restaurants in town and gives advice for everything from work lunches to godchild treats.

-

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attached

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attachedUpper House in Derbyshire shows why the Kinder landscape was worth fighting for.

By James Fisher

-

The Great Gatsby, pugs and the Mitford sisters: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 16, 2025

The Great Gatsby, pugs and the Mitford sisters: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 16, 2025Wednesday's quiz tests your knowledge on literature, National Parks and weird body parts.

By Rosie Paterson

-

Having a ruff day: Kennel Club exhibition highlights the plight of vulnerable spaniel breeds

Having a ruff day: Kennel Club exhibition highlights the plight of vulnerable spaniel breedsPhotographer Melody Fisher has been travelling the UK taking photographs of ‘vulnerable’ spaniel breeds.

By Annunciata Elwes

-

'There is nothing like it on this side of Arcadia': Hampshire's Grange Festival is making radical changes ahead of the 2025 country-house opera season

'There is nothing like it on this side of Arcadia': Hampshire's Grange Festival is making radical changes ahead of the 2025 country-house opera seasonBy Annunciata Elwes

-

Arthur Parkinson: I am a cleaner, security guard and matron to my happy hens

Arthur Parkinson: I am a cleaner, security guard and matron to my happy hensIn his first regular chicken-keeping column for ‘Country Life’, Arthur Parkinson introduces his brood and touches on the importance of good housekeeping.

By Arthur Parkinson

-

Is anyone more superstitious than a sports star?

Is anyone more superstitious than a sports star?When it comes to worrying about omens and portents, nobody gets quite so worked up as our sportsmen and women.

By Harry Pearson

-

The humble hazel dormouse — 'the flagship species of the health of our countryside'

The humble hazel dormouse — 'the flagship species of the health of our countryside'The sleepy and very sweet hazel dormouse is one of Britain's rarest mammals.

By Jack Watkins

-

The grass is always greener: Follow in the footsteps of Sir Andy Murray and play in The Giorgio Armani Tennis Classic

The grass is always greener: Follow in the footsteps of Sir Andy Murray and play in The Giorgio Armani Tennis ClassicThere’s no better time of year than the summer grass court tennis season.

By Rosie Paterson

-

You've gotta catch them all: Everything you need to know about London's giant Easter egg hunt

You've gotta catch them all: Everything you need to know about London's giant Easter egg huntFortnum & Mason, Anya Hindmarch and Chopard are among the companies that have lent a creative hand.

By Amie Elizabeth White

-

The UK gets its first ‘European stork village’ — and it's in West Sussex

The UK gets its first ‘European stork village’ — and it's in West SussexAlthough the mortality rate among white storks can be up to 90%, the future looks rosy for breeding pairs in southern England.

By Rosie Paterson