The tragic story of George Moor, the 18-year-old who won a Victoria Cross at Gallipoli and survived the Somme, only to die days before the end of the First World War

Second Lieutenant George Moor was a teenager who signed up for service at the outbreak of the First World War and battled through unimaginable horrors. John Lewis-Stempel tells his heartbreaking tale, a chilling reminder of what our forefathers had to do to survive.

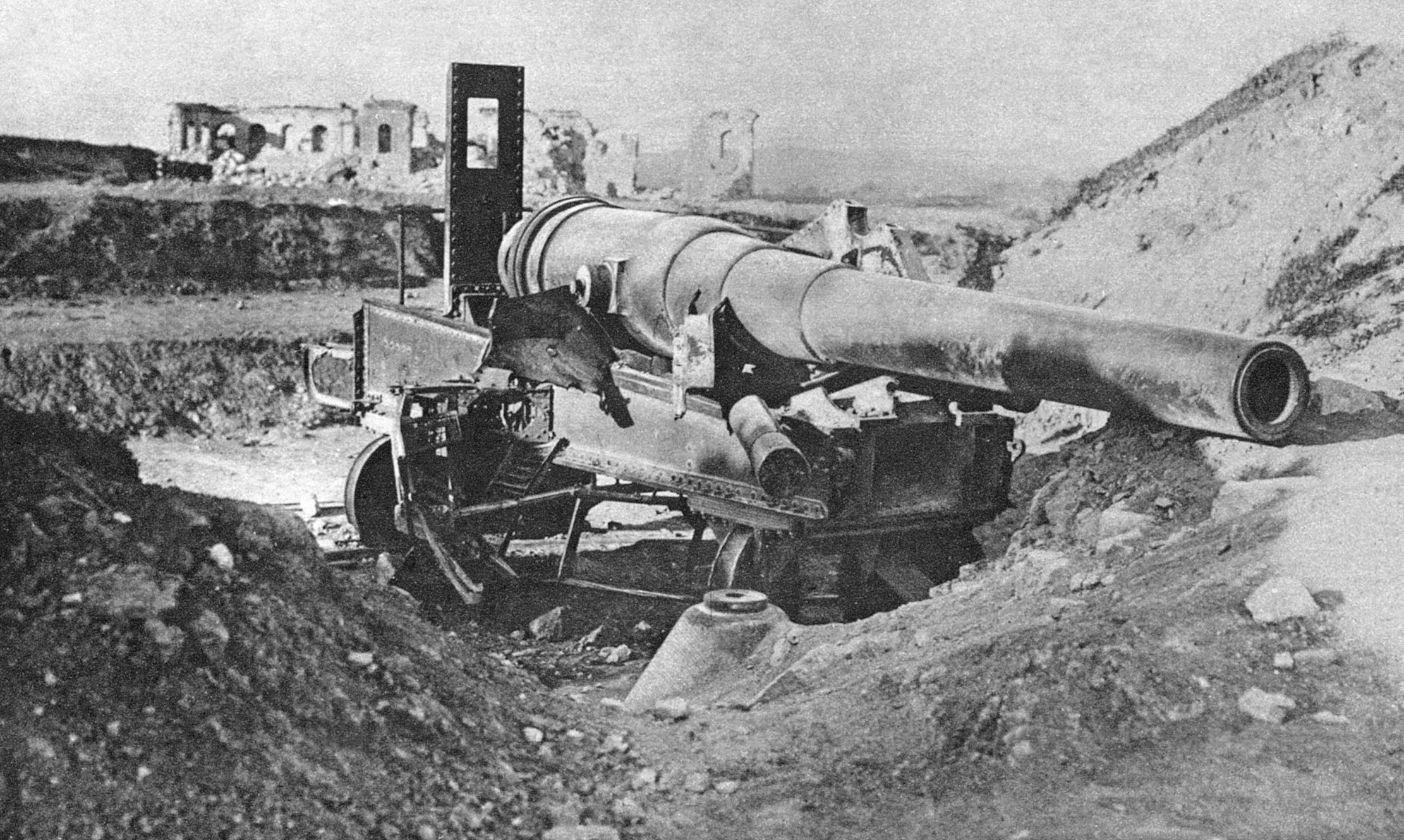

It was a place of heroes. In 1915, British Empire soldiers invaded the Turkish peninsula of Gallipoli, deemed by their First World War strategists to be the soft underbelly of the German alliance. Today Gallipoli, tomorrow Berlin! The Gallipoli campaign settled into a bloody stalemate, as if the earth had a sense of memory. The same sun-blasted ground on which Tommy fought the Turk in AD1915 saw the siege of Troy in 1260BC.

The year 1915, too, had its Hectors and Achilles, its Ajax and its Odysseus, foremost among them 2nd-Lt George Moor, who won the Victoria Cross (VC), Britain’s highest award for valour, in the trenches of Krithia, at midday on June 5, 1915. Homer would have recognised Moor and would have smiled ironically at his warrior background. It was modelled on the venerable Greek’s very own heroic works.

Initially, at least, junior officers in the First World War came from a very thin stratum of British society. Almost all were volunteers from the Edwardian public schools or, occasionally, a well-established grammar, with their curricula of Spartan cold showers and immersion in the Classics — notably Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey.

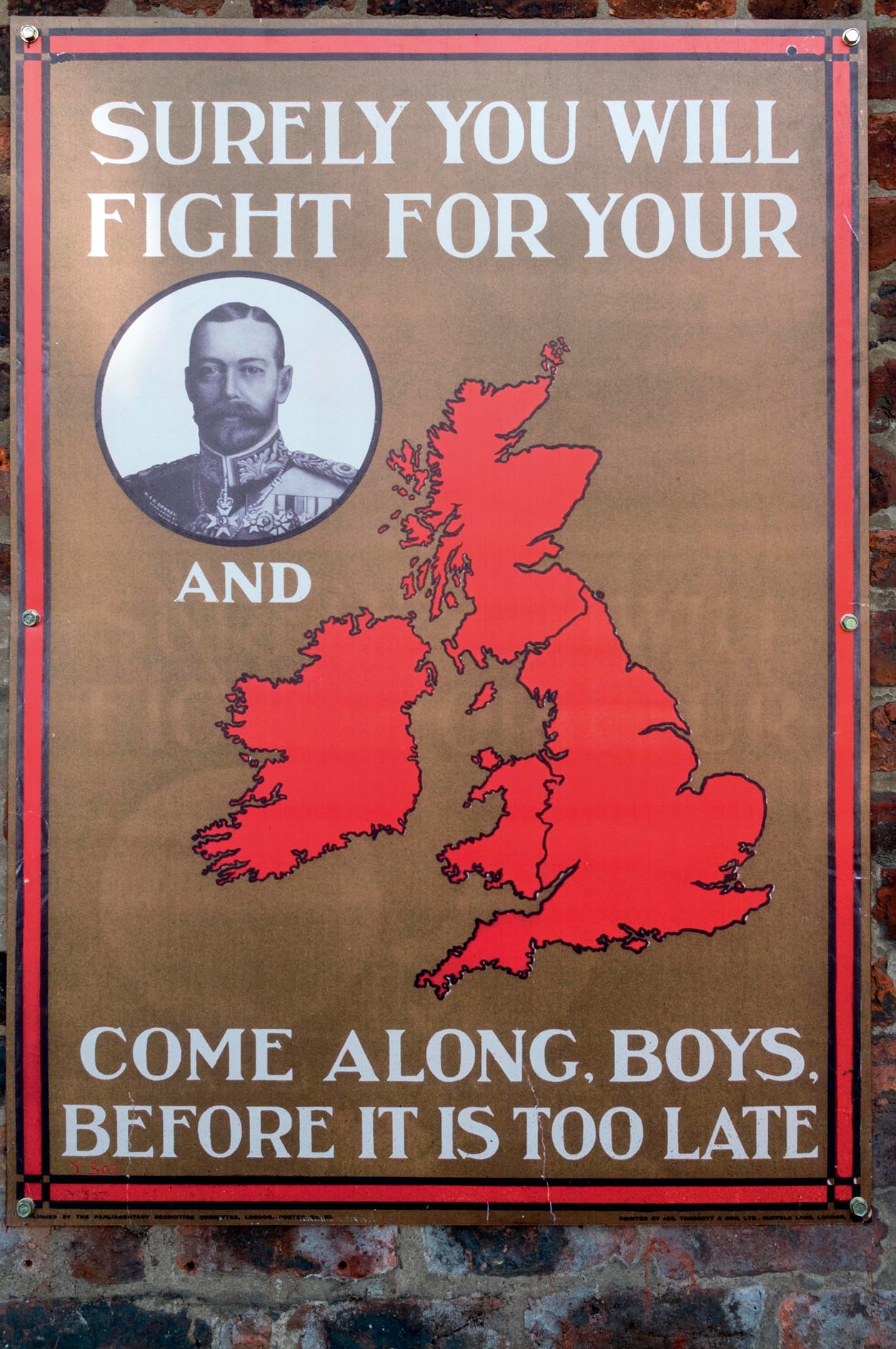

In August 1914, the values of the public school were exactly what the country at war needed. Desperately so. After all, who could withstand the highly drilled militarism of the Kaiser’s vast army — except for a corps of young British boys who believed in the qualities of courage, patriotism, selfless service, leadership and character?

The young gentleman officers were first over the top, the last to retreat. And so they suffered a blood-letting, their casualty rate often twice, triple, that of the men they led. One young subaltern, a certain J. R. R. Tolkien, found that: ‘By 1918, all but one of my close friends were dead.’

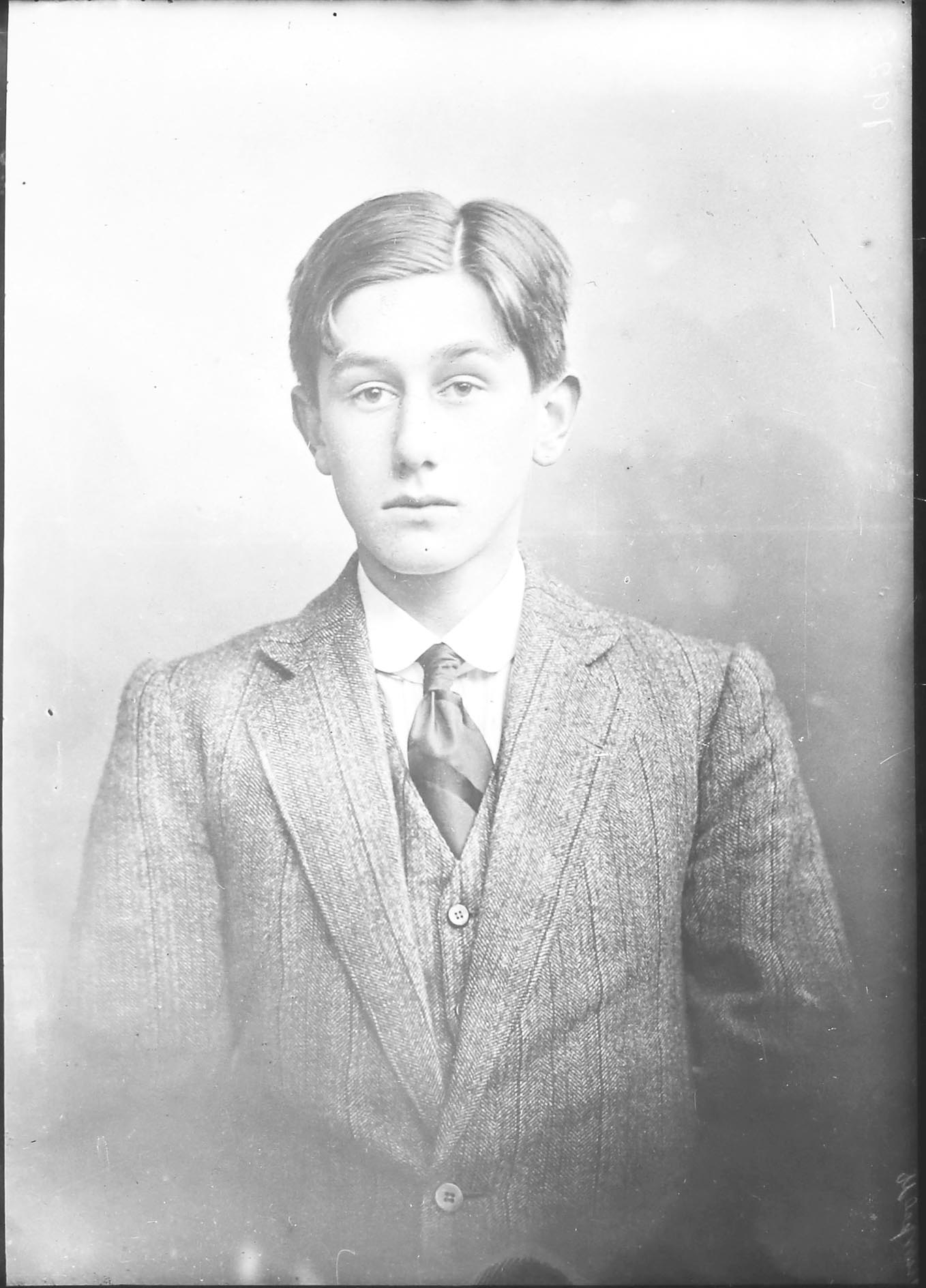

Moor fitted the paradigm of young gentleman officer to a tee. He was born in Australia, where his British father worked as a senior official in the colonial service. The family returned to England when he was six years old. He was privately educated at Little Appley at Ryde on the Isle of Wight, before attending Cheltenham College, Gloucestershire, a place of hallowed, golden buildings and an equally revered reputation for turning out servants of Empire and army. A family difficulty had preceded Moor’s entrance to Cheltenham; his mother had judicially separated from his father, who cut all ties with his children.

When war came in 1914, Moor volunteered, despite being only 17.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Some 90% of his Old Cheltonian classmates did the same. After brief training with the Public Schools Battalion, he was commissioned into the Hampshires on October 27, 1914. Poignantly, this was his father’s old regiment. We do not need to be a psychologist with the ghost of Moor on the couch to see his eternal longing for embrace by his father. History, having a sense of cruel irony, decided to send him to Gallipoli, scene of the Trojan Wars — and all their Homeric riffs on the subject of divided father and son.

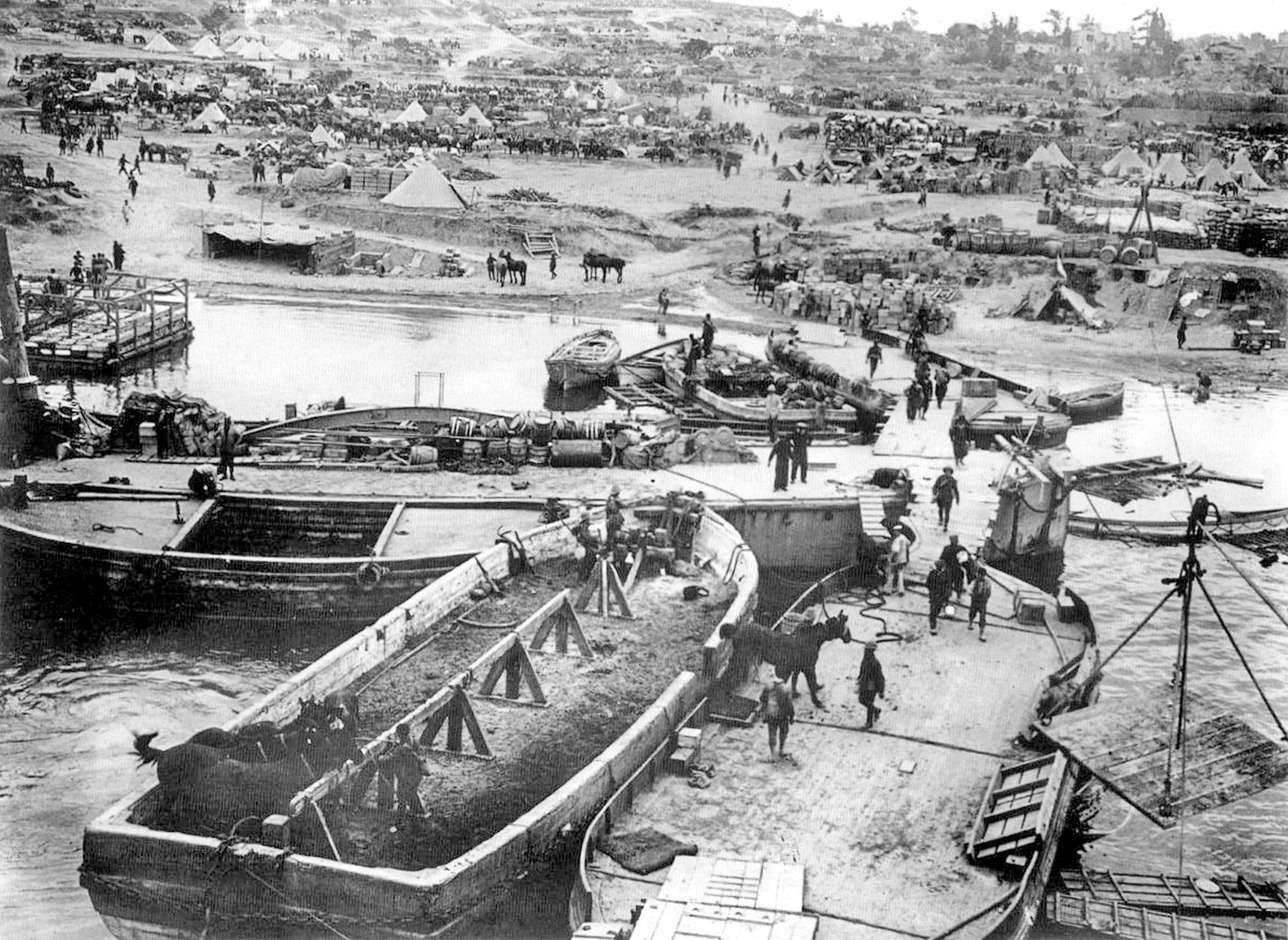

Moor’s company of the Hampshires landed on the beach at Cape Helles in April 1915 under fire, the survivors desperately digging trenches on the shoreline. There, they stood and fought, died or were wounded — as was Moor himself, two weeks after he had landed. However, he recovered in time for Krithia — his date with destiny and a VC.

The Turks had counter-attacked, the battalion to the left of his Hampshire Regiment had lost all of its officers and was, in military speak, retiring, but, in plain English, fleeing. Moor’s own commanding officer was lying plain dead. Rout to the left of him, rout to the right of him, rout to the front of him.

Moor’s VC citation noted: ‘Second Lieutenant Moor immediately grasping the danger to the remainder of the line, dashed back some 200 yards, stemmed the retirement, led back the men, and recaptured the lost trench. This young officer who only joined the Army in October 1914, by his personal bravery and presence of mind, saved a dangerous situation.’ Moor, a young officer? Born on October 22, 1896, he was a boy of 18. On such callow shoulders lay, in the First World War, Britain’s hope, not even of victory, but of salvation. Stemmed? Moor shot dead with his Webley revolver four of his own side to stop the disorder — surely, his was the hardest VC of the war.

For too long, our pop culture has traduced officers as dim, braying donkeys — pace Lt the Hon George in Blackadder Goes Forth — or hand-wringing poets, such as Wilfrid Owen and Siegfried Sassoon. They were young, but they were soldiers. As Private Burrage noted in his 1930 memoir: ‘I freely own that it was the British subaltern who won the war.’

Moor was sent home to England after Gallipoli on a dysentery sick leave and there followed stints in admin and troop training, but, afterwards, he returned to what he wanted, what he did well, which was fighting. The young gentlemen always went back.

Posted to the 1st Hampshires for the closing actions of the Somme in 1916, Moor served on the Western Front until he was severely wounded on December 23, 1917. During this period, he was awarded a Military Cross (MC) for ‘conspicuous gallantry and skill’ after carrying out a daylight reconnaissance in the face of heavy machine-gun fire.

Another convalescence in England ensued, before Moor received a posting to general staff, which should have meant Champagne and a château HQ. Not if you were George Moor. On October 20, near Pijperstraat, noting that a British attack had stalled, he intervened and restarted the advance. The citation for the bar to his MC lauded his ‘fearless example’.

The gods of war, as those who served in the first Trojan War testified, are cruelly capricious. They killed Moor not with a warrior’s battlefield bullet, but with Spanish Flu. This was on November 3, 1918, a cosmically jocular week before Armistice. Yet who can doubt he was worn out by military endeavour? At 22, he looked, in photographs, twice his age.

Moor lies in a corner of Flanders Fields, Bois-Grenier, that is forever England. On his pale, white headstone is carved the inscription Vincam et vincam. Win and win again. A suitably Classical epitaph for a modern Hector.

John Lewis-Stempel is the author of ‘Six Weeks: The Short and Gallant Life of the British Officer in the First World War’

The six varieties of poppy every gardener needs to know

From common poppy and the poum poppy to the bright yellow Welsh poppy, Jack Watkins takes a look at these

The poppy maker: ‘I was very weak, very emotional and in a bad place when I started, but I’m back to my old self again now’

Wish Lloyd battled a traumatic childhood, the army, an athletics injury and homelessness to find his place at the Poppy

How the poppy captured the imagination of the nation

Poppies aren't just beautiful, natural flowers lighting up the countryside; they're inextricably linked with our history. Jack Watkins looks at

-

Why British designers dream up the most desirable hotels

Why British designers dream up the most desirable hotelsWhen it comes to hotel design, the Brits do it best, says Giles Kime.

By Giles Kime Published

-

The five minute guide to 'The Great Gatsby', a century on from its publication

The five minute guide to 'The Great Gatsby', a century on from its publication'The Great Gatsby' sold poorly the year it was published, but, in the following century, it went on to become a cornerstone of world literature.

By Carla Passino Published