The story of the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior, the brainchild of a Liverpool curate that touched the world

A century on from its inauguration, the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior still has the power to move us — and the tale it tells is one of anguish, not triumphalism. Clive Aslet looks at how this monument came about.

There was no doubt in the mind of The Times’s leader writer about the significance of the event. The ceremony, he wrote, had been ‘the most beautiful, the most touching, and the most impressive that in all its long, eventful story this island has ever seen’. Hyperbole was not the common stock in trade of the paper in 1920, but seemed merited for the Unknown Warrior, laid to rest in Westminster Abbey on Armistice Day that year.

As the Cenotaph did, the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior, now a century old, immediately captured the hearts of the emotionally tongue-tied British people as an appropriate expression of their deepest thoughts and feelings. Today, these monuments still resonate and feature in acts of remembrance each year, but their original meanings may have been lost. Earlier this year, the Cenotaph was even attacked by protesters. It is more important than ever to recover their stories. That of the Unknown Warrior is about the anguish, not triumphalism, of war.

The unveiling of the Cenotaph in its present form and the burial of the Unknown Warrior were conceived as parts of the same ceremony. Sir Edwin Lutyens, who had been asked by the Prime Minister himself to design the Cenotaph, made it a piece of abstract mathematics. It is devoid of religious imagery, such as the cross that features on many war memorials, because the architect believed it should represent all the Fallen from across the Empire: Hindus, Muslims, Jews and atheists, as well as Christians.

By contrast, the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior was dug from the ancient soil beneath Westminster Abbey; it is a Christian monument, within the church that also serves as the national Valhalla in remembering heroes and great people. It was, however, equally egalitarian in conception. The idea didn’t arise from the mind of a government committee, but from that of a padre, David Railton, whose tattered Union Flag hangs nearby. Railton didn’t hold with pomp, titles or even war and would have preferred it to have been called the Tomb of the Unknown Comrade — which was too much for an establishment rattled by events in Russia.

Railton was the son of a Methodist minister who became a Salvation Army commissioner; he would be buried in a grave beside that of his friend, William Booth, the founder of that peaceful army. This didn’t make for an easy childhood: his father was often absent, in all senses, whether preaching the gospel around the world or communing with his God. ‘One minute he would talk with us or to one of our school friends, and the next minute to his Father in Heaven,’ Railton later remembered. Echoing other children with eccentric parents, he and his brother coped with the embarrassment by shutting ‘our eyes in order that we might not see the surprised expression of the children and grown-ups passing by’.

At Keble College, Oxford, he met Christopher and Noel Chavasse, twins whose father, Francis Chavasse, was the Bishop of Liverpool. In a city riven by factionalism of evangelicals, Anglo-Catholics, Orangemen and non-conformists, the bishop exercised what his Times obituary would describe as a ‘singular power of bringing together people of all creeds and conditions’.

This loving and inclusive approach profoundly impressed Railton. It was in Liverpool that he became ordained into the Church of England and served his first curacy. In 1910, he married Ruby Wilson, the daughter of the owner of a chain of grocery shops who lived at Kirklinton Park, Cumberland. They subsequently lived on the south coast and he was a curate in Folkstone, Kent, from where he took leave of absence to serve as a padre in France.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

At Oxford, Railton had joined the Oxford Volunteers, a forerunner of the University Officers’ Training Corps, as a private. In the trenches, he shared the privations and dangers of the troops to the extent that, in 1916, he was awarded the Military Cross. According to the citation, it was for ‘conspicuous gallantry in action. He rescued an officer and two men under heavy fire, displaying great courage and determination. He has on many occasions done very fine work’. It was an achievement he always played down as ‘the kind of thing [that] happens constantly among officers and men of the Army’.

As Andrew Richards reveals in his biography of Railton, The Flag, he was also acutely aware of the stresses suffered by ordinary soldiers. Writing to ‘My darling Ruby’ in 1916, he described the battle of High Wood on the Somme: ‘We are now burying the bonny comrades who were with us before — it is dreadful!’ Several had suffered shell shock, certainly, in his opinion, ‘caused not just by the explosion of a shell nearby, but by the sights and smell and horror of the battlefield in general’.

Wherever he went, Railton took a Union Flag to use as a cloth for communion. Later, he wrote an unpublished account of it as The Story of a Padre’s Flag, told in the voice of the flag, in which he describes the last communion given to a deserter, the flag being spread on the grass. Soon afterwards, the deserter was shot in a wood.

Railton was beside himself with anger, but stayed with the army. For a time, the flag was lost when his pack was accidentally thrown out of a train. Happily — almost miraculously — the pack was returned to him some weeks later. He was able to revive his cherished intention, ‘when this terrible business is over’, of offering the flag to a cathedral in London.

In 1931, Railton described the origin of another inspiration in Our Empire magazine. At Armentières in France, he saw the white cross over a grave, marked with the words ‘Unknown British Soldier’. The body of an unknown soldier — later termed ‘warrior’ to include all services — would be brought back to Britain and buried in Westminster Abbey. It would represent the sacrifice of all who had fought. The emotional charge was enhanced by the ruling, early in the war, that the bodies of all the Fallen would remain where they had died; there would otherwise have been the risk that the families of officers would have been able to repatriate their dead, when other ranks could not afford to. Later, in the beautiful cemeteries of the Imperial War Graves Commission, every headstone would be identical, whatever the rank of the soldiers named on them: they were equal in death.

It was on August 16, 1920, that Railton wrote to the Dean of Westminster, proposing his idea for the flag and a tomb to the Unknown Dead. War Office permission was granted and Brig-Gen L. J. Wyatt was tasked with recovering a suitable body. Four digging parties were sent to the battlefields of the Somme, Aisne, Ypres and Arras, to find the remains of soldiers killed early in the war (and so less likely to be recognised), with no identifying marks about them, but wearing British uniforms. The four parties never met; they could, therefore, never know whether it was their body that had been chosen.

The process was almost theatrically thorough. Both Protestant and Catholic rites were said over the cadaver, which was placed in a casket given by the British Undertakers Association, made of oak from Hampton Court. Mounted on top of the coffin was a crusader’s sword, a gift from the King. The body was escorted to the quay at Boulogne by French cavalry and the departure of HMS Verdun was accompanied by a gun salute.

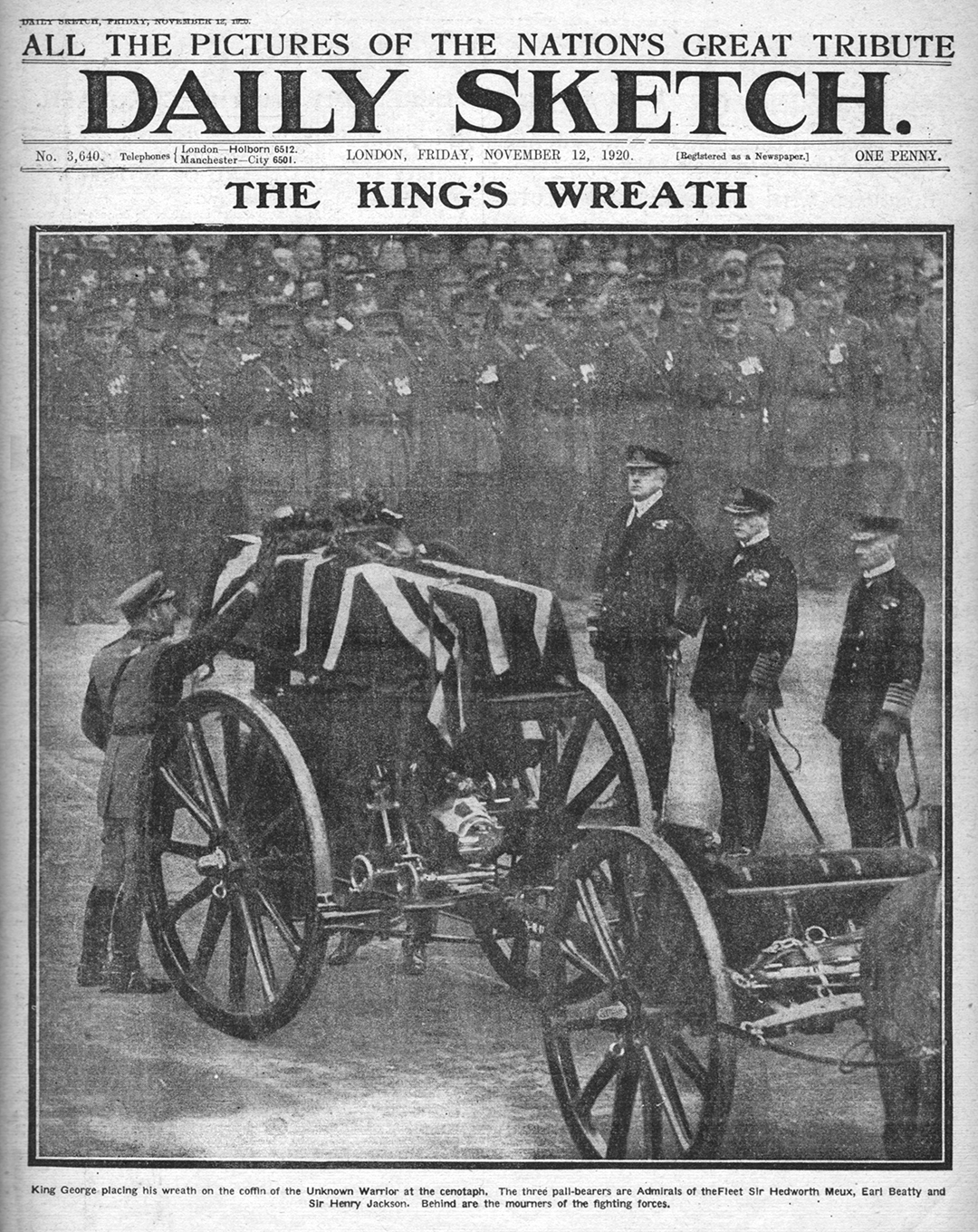

The ceremonies on November 11 were under the control of Lord Curzon, impresario of the most splendid of the Delhi Durbars in 1903. He hadn’t lost his touch. The procession moved out of Victoria Station on a circuitous route to Whitehall that took it to Hyde Park Corner, through the Wellington Arch and down Constitution Hill to The Mall. Silent crowds lined the way. At the Cenotaph, the King placed a wreath of bay leaves and red roses on the coffin and, on the first stroke of 11am, pressed the button that released the two huge Union Flags covering the memorial. At the last stroke of 11, the two-minute silence began. The gun carriage then moved off towards the Abbey, behind the Archbishop of Canterbury, to the sound of Chopin’s Funeral March.

The flag was hung on Armistice Day the following year. That, however, was not the last time that Railton would be in the news. By now vicar of St John the Baptist at Margate, Kent, he had set out earlier in the year, wearing an old coat and with a shilling in his pocket, to tramp the country and discover how former servicemen were faring.

Many were unemployed. A week after the Armistice service, he gave his story to the Evening Standard. ‘Vicar Turns Tramp’ was a headline that went around the world. Commemoration was important; so were human needs.

D-Day veterans in their own words: 'A lot of men did very brave things. I simply did what I was told to do'

The surviving veterans of D-Day are well into their nineties, but many still remember the events with stark clarity. Three