What it's like to have a prime seat at a Royal Coronation by John Betjeman, who reported for Country Life in 1953

The late, great Poet Laureate John Betjeman was among the congregation when Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II was crowned in 1953 — and he wrote about it for Country Life. We're very proud to reproduce that article now — The Queen's Coronation: In The Abbey by John Betjeman.

I had what must have been one of the best seats in the Abbey. I was at the west of the South Transept sitting among many distinguished admirals, the least decorated and the least important person within sight. I could see the Throne itself on the "theatre" which is a golden carpeted space at the crossing of the Transepts. The Throne is a gilded chair upholstered in pink silk, almost like the kind of thing you see in the drawing room of an Irish Roman Catholic prelate.

The Throne faces east, and east of this I could see King Edward's Chair, where the sacred rite of Anointing the Queen takes place. Beneath the Chair I could see the Stone of Destiny, but I noticed that a cushion had been put on it for the comfort of the Queen. And then east of the Chair I could see the Altar itself, and the fald stools at which the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh would kneel when they made their Communion.

"This ancient rite is something much more important and formidable than anything one can touch and see"

***

These moments of waiting are somewhat of a social occasion. There is almost the feeling of a fashionable wedding in St. Margaret's, until the music begins, and the people stop talking, and stop looking at one another, and crane down to this space of golden carpet which is soon to be, for all of us at any rate who are gathered here, the heart of the world. Then the processions which precede the Queen come in, each with its pair of heralds. The drama heightens as the Dean and Prebendaries of the Abbey enter bearing the Regalia, and the Litany is sung, as it has always been sung at the Coronation since the 12th century.

The glorious copes of blue and gold which the Prebendaries wear are so far the must magnificent vestments we have seen. Two more heralds, highly coloured as playing cards, and then the Princes and Princesses of the Blood Royal. The lights grow brighter, the golden floor looks more golden, and a feeling of expectancy is everywhere, even among those who are unlucky enough to see nothing because there is a pillar in their way. And, now comes Somerset Herald and Windsor Herald, two ushers and our exquisite Princess Margaret, the Lord Chamberlain behind her, and then the Queen Mother with the Dowager Duchess of Northumberland as her Mistress of the Robes. The Regalia are delivered to the Peers appointed to bear them, and there is a silence.

We can hear the bells of the Abbey faintly outside. We can hear shooting in the streets, and now the whole Abbey is ready for the entrance of the Queen.

The choirs sing the psalm "I was glad when they said unto me, We will go into the house of the Lord...," which dates from the Coronation of Charles I. There must surely be something supernatural about this moment. All sense of a social occasion is gone, and we are a nation gathered for a religious rite. Chaplains in scarlet, Free Church Ministers in black silk, six Heralds, robed Knights and Peers, and then the Standard Bearers, the Cross of York, and its Archbishop behind it, the Chancellor, wigged and in black silk, the Cross of Canterbury, and the Archbishop, the Duke of Edinburgh, the Regalia, the Patten, the Bible and the Chalice, borne by Bishops in copes — and then the Queen herself. She moves with grace, but without pride. She is in white, with a diadem, not a crown, on her head and her six train-bearers are in white and gold dresses, which contrast with the long blood-red crimson of her train.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

***

For all its splendour and solemnity the Coronation service is simple and full of meaning. It is not pageantry, unless you call the sacraments of our old Church of England pageantry. There are four things to follow in this service, and I want to give each of them their significance.

The supreme moment in the ceremony.

The Archbishop of Canterbury places the St. Edward's Crown on the Queen's Head.

First, the Recognition. Here is the Queen, a beautiful young woman, uncrowned, standing at the entrance to the Sanctuary, the Archbishop before her. She does not make herself Queen, as did the Tsars and other despots; she is presented to her people by the Archbishop, and this, next to the Anointing and the Communion, is the most touching part of the service. First the Archbishop presents her to the clergy, who sit in the Sanctuary. Then to us in the South Transept, then to the people in the Nave, then to the East Transept, always with the same words: "Sirs, I here present unto you Queen Elizabeth, your undoubted Queen: Wherefore all you who are come this day to do your homage and service, Are you willing to do the same?," and each time, we, her people, answer "God save Queen Elizabeth," and she makes a little curtsey. There is a silence and trumpets sound.

Then from her chair she solemnly swears to govern her peoples to support the Law and the Church, and ratifies her oath at the Altar. At this point there is an excellent Protestant interpolation introduced in 1689 at the crowning of William and Mary, when she is presented with the Holy Bible. It was a good idea at this Coronation to have the Moderator of the Presbyterian Church of Scotland saying "Here is Wisdom; this is the royal Law; these are the lively Oracles of God."

The third, and to me the most touching, part of the service is here, when the Coronation proper begins with the Anointing. The Queen was divested of all her jewellery, and she stood in a plain white robe, looking little more than a child, on whom all the weight of the world was to be thrust. Edgar, the first King of all England, was anointed in 973; Queen Elizabeth the Second was anointed today. The Dean of Westminster, a tall, monkish, medieval-looking man, came forward with the golden Ampulla in the form of an eagle which contains the oil. I saw him dip a spoon into which the Archbishop dipped his thumb. Few people can have seen this, because a golden canopy was held over the Queen's head, as she sat in King Edward's Chair, by four Knights of the Garter in their dark, blue-black robes.

The Archbishop anoints her on the hand, on the breast and on the head. This is the sacrament of unction, and now we need have no fear that she will be unable to maintain her office so that the presenting to her of the Spurs and the Sword of Justice will not be more than she can bear. She is wise, now the Bracelets of Wisdom are put on her. She stands up in all her dignity, strong enough to be a Queen. The Dean of Westminster and the Mistress of the Robes dress her first in a muslin undergarment, and then in a gold super-tunica belted with a rich girdle.

Here I must say how supremely well the Mistress of the Robes and the Dean carried out this delicate office. It must he difficult to make the robing of someone in public, even a Queen so dignified as ours, not look slightly ridiculous, but they managed to make it something beautiful and tender.

When the Queen has had the symbols of all the cares of being a Queen given her, those Regalia of which you will have read elsewhere, the Archbishop goes to the Altar and fetches the heavy glittering Crown of St. Edward which outshines all the diamonds in the Abbey, and he puts it reverently on her head. Then we all shout, "God save the Queen." The Archbishop blesses her, the choir sings, and the Archbishop blesses us as we kneel, and she is led to the Throne.

***

This was a great moment. Carrying the sceptre in one hand, the Rod in the other, with a golden train, and with a heavy Crown on her head, she ascended the Throne. There was no sense, to put it bluntly, of this being a balancing feat.

She was truly a Queen, and had the strength to bear these ornaments of office. First, her Bishops and Clergy paid homage to her; then her Peers.

The end of the Coronation service is, of course, what it should be in a Christian country. We do not worship the Queen — we worship God, and she worships Him in the most perfect way she can worship Him on earth by receiving the Holy Communion. The Duke of Edinburgh knelt beside her at the Sanctuary steps, and once again they were ordinary people receiving the Body and Blood of Christ from the Archbishop. And because priests are always communicated first, the Archbishop of York and five other Bishops received Communion before her.

I can understand why materialists, whether they are communists or mere money worshippers, so detest the Coronation, and try to decry it with heavy satire and complaints about expense and pageantry. This ancient rite is something much more important and formidable than anything one can touch and see. From today's ceremony goes out the spirit which decked the little streets which the Queen herself may never see, with red, white and blue.

-

Why British designers dream up the most desirable hotels

Why British designers dream up the most desirable hotelsWhen it comes to hotel design, the Brits do it best, says Giles Kime.

By Giles Kime Published

-

The five minute guide to 'The Great Gatsby', a century on from its publication

The five minute guide to 'The Great Gatsby', a century on from its publication'The Great Gatsby' sold poorly the year it was published, but, in the following century, it went on to become a cornerstone of world literature.

By Carla Passino Published

-

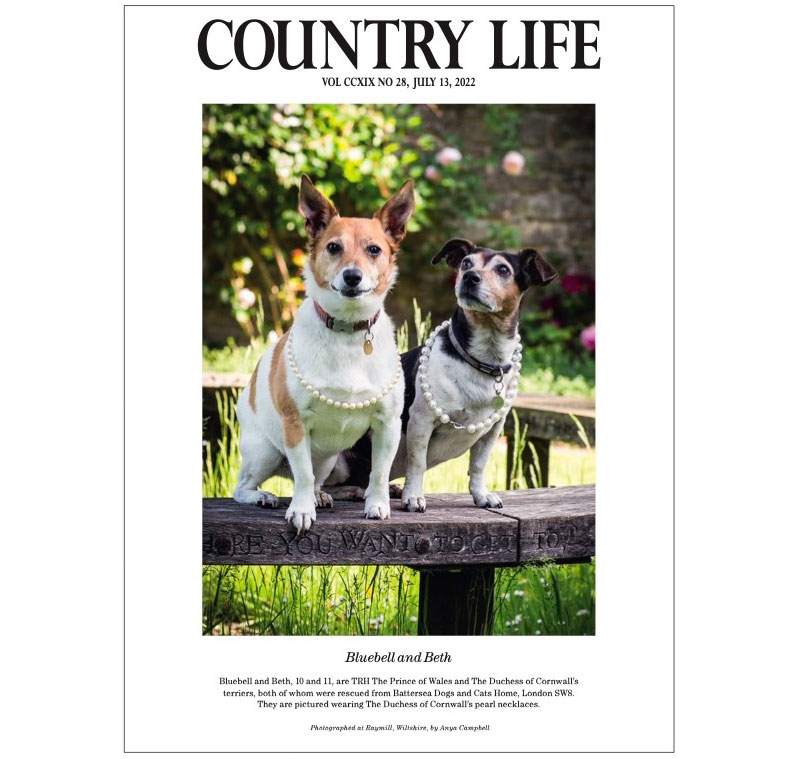

Queen Camilla says 'sad farewell' to her beloved Jack Russell, Beth

Queen Camilla says 'sad farewell' to her beloved Jack Russell, BethHer Majesty Queen Camilla's much-loved Jack Russell terrier Beth has died.

By Toby Keel Published

-

Curious Questions: Why do we carve pumpkins at Halloween?

Curious Questions: Why do we carve pumpkins at Halloween?The devilishly smiling image of Jack O'Lantern is inseparable from Halloween, but what's the story behind it? Martin Fone explains — and discovers that the festival many complain about as an American import has been this side of the Atlantic for centuries.

By Martin Fone Published

-

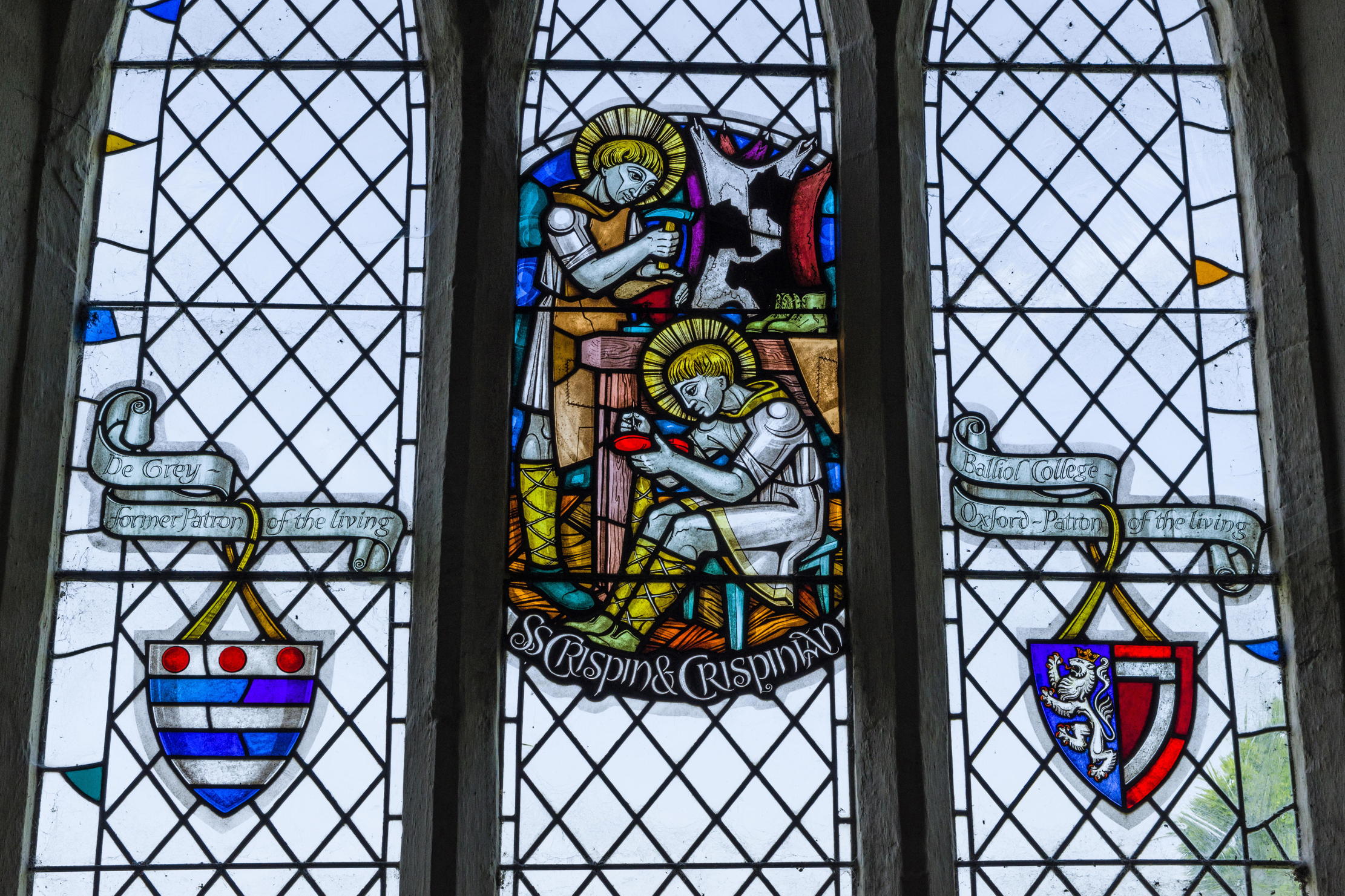

Who was the real St Crispin, and what did he have to do with the Battle of Agincourt?

Who was the real St Crispin, and what did he have to do with the Battle of Agincourt?You have questions about Shakespeare's most famous speech. We have answers.

By Ian Morton Published

-

Dawn Chorus: Watching telly with The Queen, the one-bedroom wreck that fetched £2 million and our Quiz of the Day

Dawn Chorus: Watching telly with The Queen, the one-bedroom wreck that fetched £2 million and our Quiz of the DayPlus a Paddington Bear hamper, an ancient tree and a house with a terrifying price tag — it's Friday's Dawn Chorus.

By Toby Keel Published

-

Do you know your apple-catchers from your tittamatorter? Take a crash course in the UK's local languages

Do you know your apple-catchers from your tittamatorter? Take a crash course in the UK's local languagesWith experts warning that regional accents could disappear within decades, our sometimes quaint and, often, bizarre dialect words are becoming ever-more precious.

By Victoria Marston Published

-

Curious Questions: Why do barristers and judges wear wigs?

Curious Questions: Why do barristers and judges wear wigs?Like marmalade on toast, saying sorry and the Shipping Forecast, there are few things more typically British than the courtroom wig. Agnes Stamp explains why our barristers and judges wear them.

By Agnes Stamp Published

-

Fit for a (very small) queen — a dolls' house with running water, electricity and working lifts

Fit for a (very small) queen — a dolls' house with running water, electricity and working liftsQueen Mary's Dolls' House celebrates its 100th anniversary with a brand new exhibition and a reimagined display at Windsor Castle.

By Annunciata Elwes Published

-

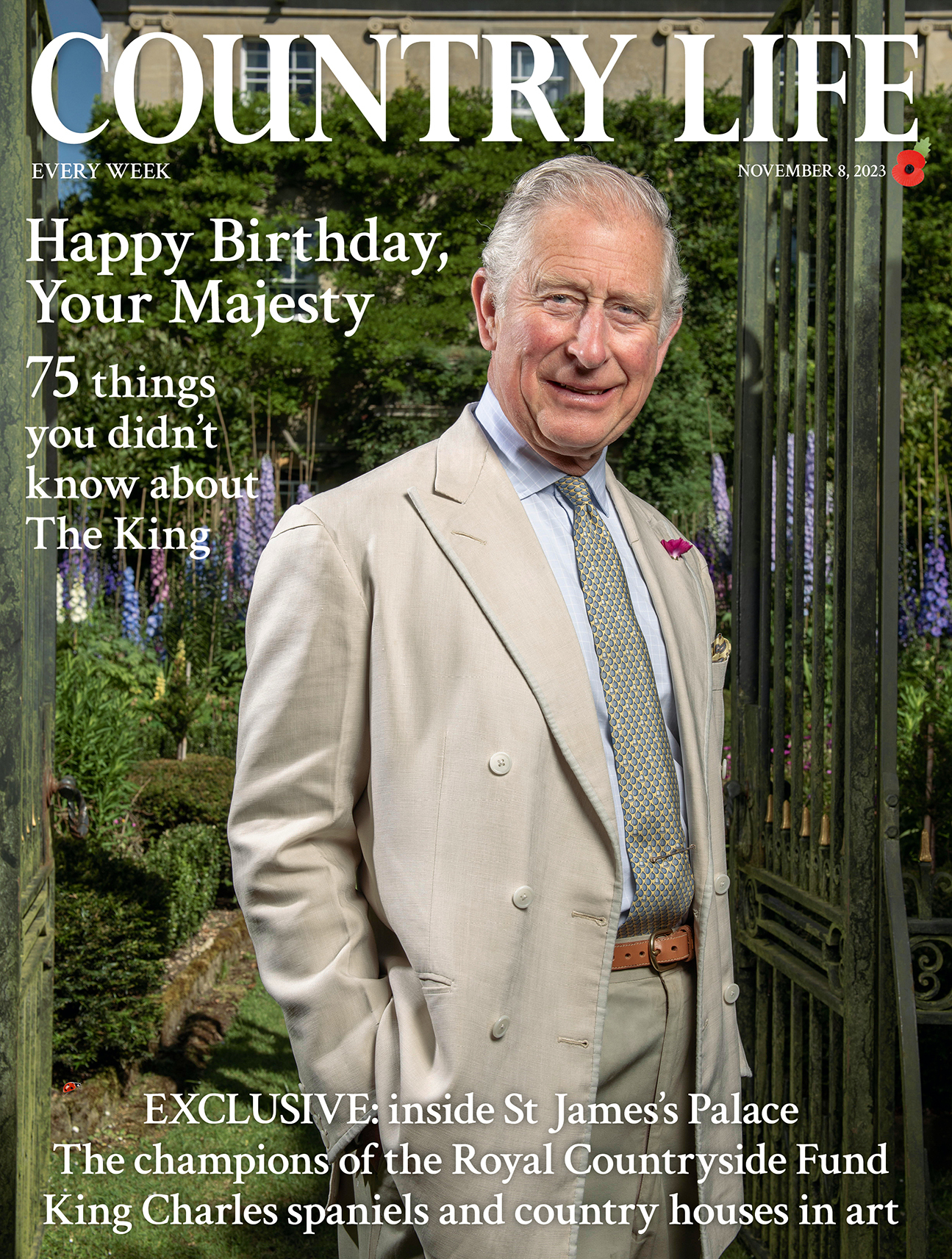

75 things you never knew about King Charles III as he celebrates his 75th birthday

75 things you never knew about King Charles III as he celebrates his 75th birthdayOn The King’s big day, Amie Elizabeth White reveals 75 things you might not know about our monarch.

By Amie-Elizabeth White Published