The great Blue Plaque mystery in London

Dozens of blue plaques have gone missing down the years, and English Heritage is determined to try and find them.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

William Hogarth, Lord Byron, Sir David Wilkie, John Milton and Francis Trevelyan Buckland: have you seen them? English Heritage is asking for the public’s help to find more than 50 missing Blue Plaques. The campaign launches today and is marked by the reinstating of surgeon Joseph Lister’s plaque, which has been lost not once, but twice, most recently amid building work in 2017.

Since its inauguration in 1866, the famous scheme has been expanded to cover more than 1,000 plaques across London commemorating notable people. The ever-changing streetscape of the city has presented its challenges; the first ever plaque, for Byron at his home in Marylebone and unveiled by the Society of Arts in 1867, is on, we believe, its fourth iteration.

First, his house on Holles Street was demolished in 1889 (the plaque could still exist), another one was lost during the Blitz, after which a non-standard plaque was replaced in 2012 — the current one decorates a somewhat unpoetic branch of John Lewis closest to the original spot.

Napoleon III’s is thought to be the oldest surviving, installed in 1867 at the St James’s home he hurriedly left in 1848, his bed unmade and his bath full of water, upon hearing of Louis Philippe’s abdication. Some buildings have two, such as 29, Fitzroy Square (George Bernard Shaw and Virginia Woolf); Handel and Jimi Hendrix lived next door to each other in Mayfair (not in the same century, obviously) with the latter remarking: ‘To tell you the God’s honest truth, I haven’t heard much of the fella’s stuff’; and, since 2016, there has been greater effort to commemorate women, including Christina Broom, Britain’s first female press photographer, and jazz singer Adelaide Hall this year.

After the turn of the century, the scheme was managed by London County Council (LCC) for 64 years, followed by Greater London Council, then EH from 1986. As such, the style of the Blue Plaques — some of which are not even blue, they can be brown or terracotta, too — varies a little. They should not be confused with other plaques put up by various councils.

‘These lost plaques are part of the story the London Blue Plaques scheme has been dedicated to telling for the past 158 years. The story, not only of London, but of the breadth of human endeavour,’ says EH curatorial director Matt Thompson. ‘Whether they are on a building for all to see or safely in our stores, together with others already returned to us, each plaque documents the history of what is arguably the oldest commemorative scheme in the world. That is why we would like to find out if any of the “lost” plaques survive.’

The Case of the Missing Plaques

Numbered among the missing is William Hogarth, whose Blue Plaque was installed in the 1920s; naturalist Francis Trevelyan Buckland, who, in 1847, took his pet bear dressed in cap and gown to an Oxford party; and poet John Milton.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Engraver Charles Turner (b.1774, no relation to J. M. W.) was commemorated by the LCC in 1924. His plaque on Grade II-listed 56, Warren Street, W1, hasn’t been seen since the house was re-fronted in the 1990s, and Warwick Crescent in Little Venice, where the poet Robert Browning lived and worked from 1861–87, has also lost its plaque.

Others with the potential to be found in someone’s attic commemorate Australian novelist Henry Handel Richardson; Romantic painter Sir David Wilkie; historian, curate and biographer John Strype (b.1643), for whom Strype Street, E1, is named; astronomer Francis Baily; composer Sir Arthur Sullivan, one half of Gilbert & Sullivan; and the aforementioned Byron.

Some have already been found; 18th-century actor and playwright David Garrick’s early Society of Arts plaque, for instance, appeared in a Woolley & Wallis auction in Salisbury in 2016, where it was bought by The Garrick Club, WC2. Although parts of its journey are unknown, it’s thought the plaque was removed from its home on the Adam brothers’ Adelphi Terrace when it was demolished in 1936.

Curious Questions: Does a blue plaque make your house more valuable?

London’s multiplying Blue Plaques certainly add interest, but do they affect property values? Eleanor Doughty investigates.

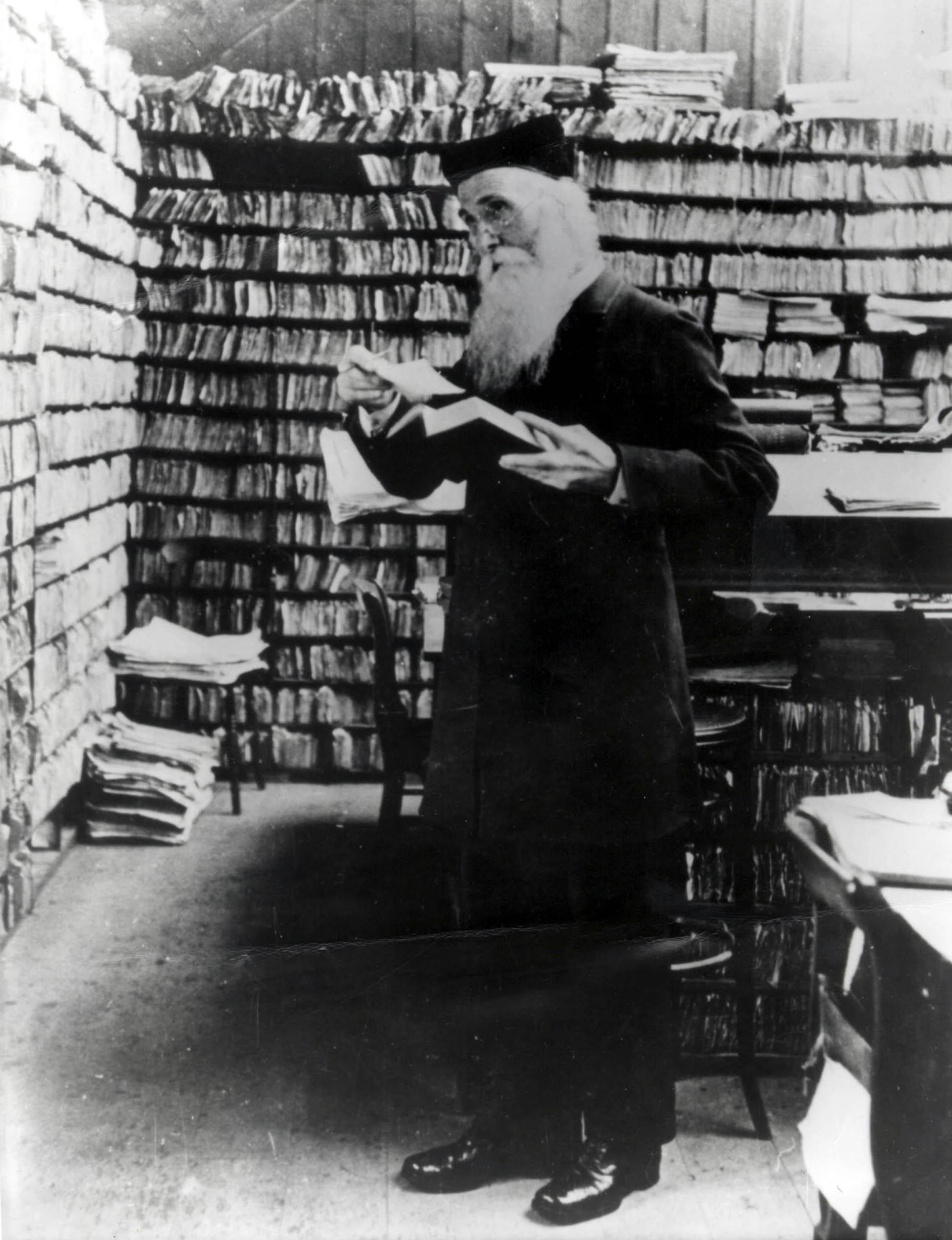

Curious Questions: Who created the Oxford English Dictionary?

Martin Fone, who has long been fascinated by words, digs in to the story of how Sir James Murray created

How the Bloomsbury Group shaped life in London WC1

There’s more to the Bloomsbury Group than squares, circles and triangles, says Rosemary Hill, who explores what drew its members

The day Elton John invaded the Cotswolds

As Elton John’s Rocket Records celebrates its 50th anniversary, former NME editor Steve Sutherland remembers the very boozy launch party,

Annunciata is director of contemporary art gallery TIN MAN ART and an award-winning journalist specialising in art, culture and property. Previously, she was Country Life’s News & Property Editor. Before that, she worked at The Sunday Times Travel Magazine, researched for a historical biographer and co-founded a literary, art and music festival in Oxfordshire. Lancashire-born, she lives in Hampshire with a husband, two daughters and a mischievous pug.