The M25 and A3 junction's 'wildlife bridge' shows the way forward for Man and Nature

We must ensure that the UK’s first ever heathland green bridge, straddling the A3 and a lifeline for diminishing wildlife, isn’t the last of its kind to open, says John Lewis-Stempel.

Why did the hedgehog cross the road? Perhaps it was out hunting slugs or seeking a mate. Unfortunately, it was run over when on its nocturnal ramble; up to 335,000 hedgehogs die each year on UK roads. Flattened. Together with about 750,000 other wild things.

How could the animals not end up as roadkill? The UK has a road network totalling about 262,300 miles, along which we drive 41.3 million licensed vehicles. People find tarmac and four wheels useful, whereas Mrs Tiggy-Winkle and friends find the road network at best a barrier, at worst a mortal experience and, somewhere in between, they discover themselves stranded in fragmented habitats with diminishing resources and a shrinking gene pool.

We Nature-caring drivers resort to helping mother duck and her ducklings across the lane in the manner of a lollipop man (or lady), or driving at 1mph when the toads are migrating and hoping they will waddle out of the way. Or, as a last resort, walking in front of the car as someone else drives, picking up the amphibians and depositing them in the verge. The truly admirable among us form neighbourhood toad patrols.

There has to be a better, more effective way of helping animals cross the road safely — and lo, there is. As the lines of tarmac on the earth proliferate, more and more roads are being constructed with provisions for the animals to pass over (or under). ‘Wildlife bridges’, ‘green bridges’, ‘ecoducts’, call them what you will, make it easier for animals to migrate, mate, eat and survive. They also connect the fragmented landscapes. Deservedly, the wildlife bridge is in conservation vogue.

The earliest recorded manmade animal bridge was erected in France in the 1950s to help hunters guide deer. Since then, designated animal crossings have gone global. Beneath Florida’s ‘Alligator Alley’, the route between Naples and Fort Lauderdale, dozens of under-passes help the scaly and the furred evade the traffic, as, in the Victorian alps of Australia a ‘tunnel of love’ permits separated pygmy possum colonies to mingle. The small Himalayan country of Bhutan has an elephant underpass and, in Java, suspended water pipes allow traverses by lorises.

“The only limitation in green bridges is human imagination”

In Europe, the animal crossings of the Netherlands carry everything from elk to wolves, bison to badgers. One of the earliest Dutch ecoducts was the 164ft-wide Terlet overpass, completed in 1990 and planted up with trees; it looks to the car driver as if the Snelweg A50 goes under a wood. Within six years, three species of deer were recorded using the Terlet pass for safe travel, together with wild boar, badger, wood mice and the common vole. Groene Woud ecoduct, also in the Netherlands, has a chain of small pools across the overpass and an access ramp for amphibians. Common toads use it.

The only limitation in green bridges is human imagination. In Brisbane, Australia, three canopy bridges woven from heavy rope allow glider possums to swing through the sky above the infernal Compton Road. A citizen project in Oslo, Norway, has created a ‘pollinator’s passage’, whereby flowers are planted on roofs and ‘bug hotels’ sited on balconies, all along a predetermined route so that bees can travel across the city via nectaring and rest stops. Think an alpine version of the human motorway services, where we stop to fill up with petrol and take a rest.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Purpose-built animal crossings, whatever practical form they take, are conservation for adults. Quite literally, they make joined-up eco-thinking. Green bridges work, for animals, but also for humans. Road accidents with animals cause injury to body and bank balance. Deer collisions alone in the UK account for 400–700 personal injuries per year, including about 20 fatalities. Zurich insurance, meanwhile, has estimated that collisions with animals cost the insurance industry more than £60 million a year in car repairs. Against this, the construction of one single overpass in Sweden enabled roe deer and moose populations to move around without having to cross the macadam — and led to a 70% local reduction in accidents caused by roe deer.

Alas, when it comes to green bridges, Britain is in the slow lane of this conservation initiative. There are estimated to be a mere six wildlife bridges in the UK. By contrast, the Netherlands — with 86,370 miles of road — has 600. Our national paucity of wildlife bridges comes despite a 2015 report, Green Bridges — a literature review, prepared for Natural England, rightly recognising their importance in transport sustainability, wildlife protection and landscape enhancement. The most famous British green bridge crosses the A21 at Scotney Castle in Kent in the High Weald National Landscape (formerly AONB). Completed in 2005, the bridge allowed the historic scenic drive to the castle to be preserved and was soon used by dormice. In London, a landscaped, parkland bridge was built to overcome the road and rail fragmentation of Mile End Park and is a reminder that wildlife passes are for town as well as country.

If Britain is late to the building of green bridges, the road ahead looks to be better spanned. Cockcrow Green Bridge will become the UK’s first ‘heathland’ green bridge, arching over the A3 just south of the M25 at junction 10, to connect the commons on both sides. Heathland is one of the UK’s most threatened habitats and the bridge is more than a connector; nearly 100ft wide, laid with heather and other appropriate shrubs, it is heathland habitat creation.

On the iron road that is HS2, a total of 16 green bridges will be built along the new £100 billion line between London and Birmingham. There will also be five green tunnels, including the 1¾-mile Greatworth Tunnel in south Northamptonshire. Network Rail has installed the first ‘dormouse bridge’ across a UK railway, a square metal tube attached to the side of an existing bridge in Morecambe Bay. Measuring 40ft long and only 10in wide, it is a bridge of miniature proportions, but connects two populations of Britain’s endangered wild hazel-dormouse population. Sometimes, all that is required to stop hedgehogs being flattened and dormice disappearing is a bridge over troubled trackways.

-

London is the place for me* (*the discerning property buyer)

London is the place for me* (*the discerning property buyer)With more buyers looking at London than anywhere else, is the 'race for space' finally over?

By Annabel Dixon

-

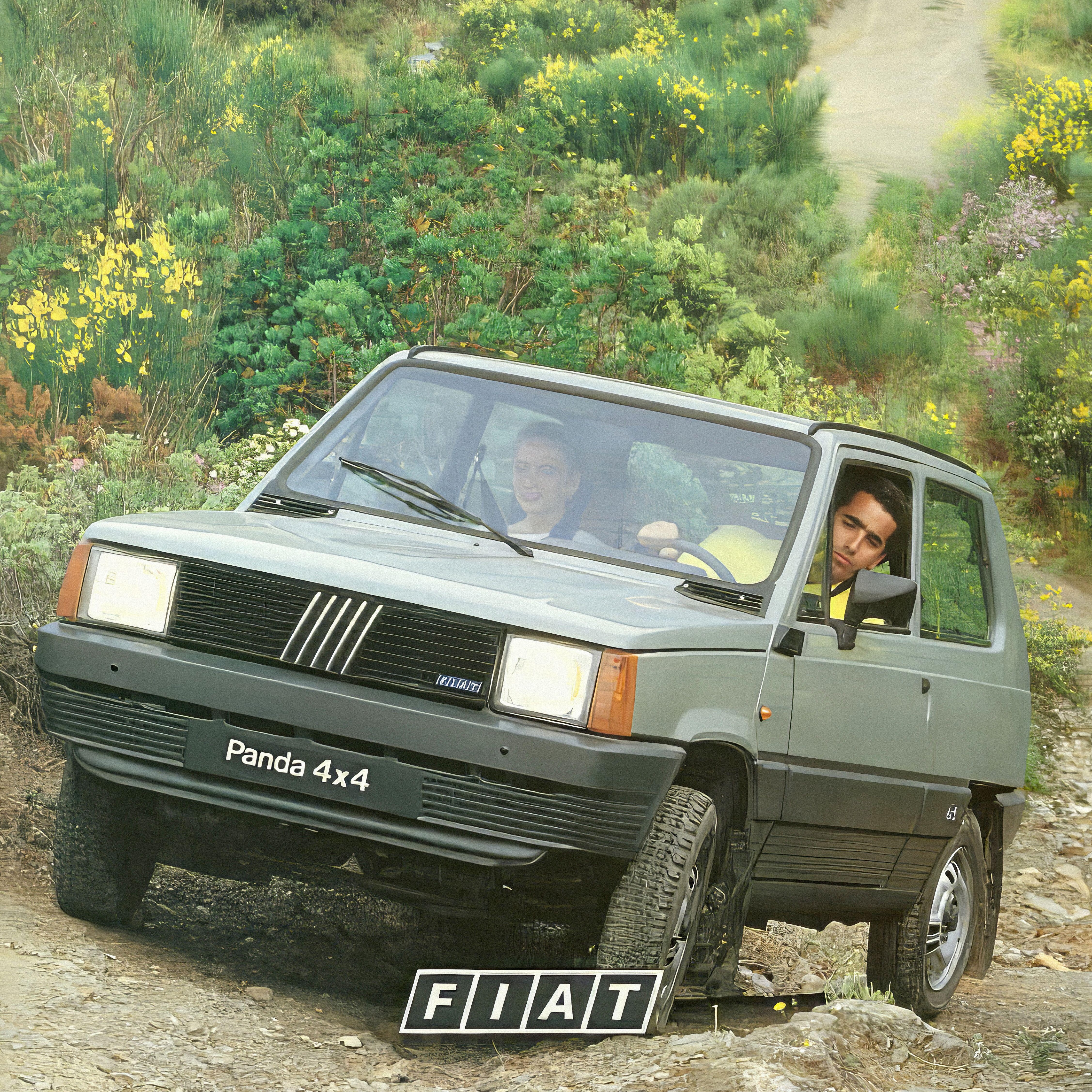

Helicopters, fridges and Gianni Agnelli: How the humble Fiat Panda became a desirable design classic

Helicopters, fridges and Gianni Agnelli: How the humble Fiat Panda became a desirable design classicGianni Agnelli's Fiat Panda 4x4 Trekking is currently for sale with RM Sotheby's.

By Simon Mills