The day Elton John invaded the Cotswolds

As Elton John’s Rocket Records celebrates its 50th anniversary, former NME editor Steve Sutherland remembers the very boozy launch party, held in the unlikely, but charming Cotswolds setting of Moreton-in-Marsh.

The date was set for Thursday, April 26, 1973. The invitations arrived in the form of a first-class Great Western Railway ticket. The ticket was clipped on boarding the train, known back in the day as a ‘football special' — a Pullman hired specifically to take supporters to matches. It set off from Paddington station at 6.40pm, with a stated return of 11.35pm. ‘Drinks, goodies, food and music,’ were promised for the journey and the destination was revealed as ‘Moreton On Marsh’. Recollections as to the food, music and goodies served on the 1½-hour journey are sketchy, however—mostly because the drinks provided on the train turned out to be a surfeit of Champagne.

The party had been arranged to celebrate the launch of Rocket Records, a new, independent label founded by Elton John, now Sir Elton. The singer had previously been signed to DJM Records with his lyricist partner Bernie Taupin. However, tensions over remuneration and, ultimately, guitarist Davey Johnstone’s desire to put out a solo album, which DJM was not keen on, prompted Sir Elton to launch his own business. The new company was named for Stephenson’s Rocket, the famous steam locomotive from 1829, and Rocket Man (I Think It’s Going To Be A Long, Long Time), the number-two hit single from Sir Elton’s Honky Château album, released in 1972. Its first employee was business all-rounder Stuart Epps, who’d jumped ship with Sir Elton from DJM. ‘Elton had just released the Don’t Shoot Me I’m Only The Piano Player album and by now all the albums were going to number one,’ says Mr Epps. ‘Elton’s career was roaring and he wanted to put something back by signing artists to his own label.’

Much like The Beatles’ Apple organisation, Rocket made it known that it welcomed musical acts to show up at the offices and audition, so one of Mr Epps’s first tasks was to find a suitable location for the label to hold a launch party. ‘We were independent and wanted to be seen that way, so nothing too fancy, somewhere where we could have a lot of fun,’ he remembers. Scouting around, he finally settled on Moreton-in-Marsh, an ancient Cotswold market town on the Fosse Way Roman road in the Evenlode Valley, some 73 miles from Rocket’s offices in London’s Soho.

The chosen venue was Redesdale Hall on Moreton’s High Street, right by the market square and barely a quarter of a mile from the railway station. Serving as the town hall, the Grade II-listed Redesdale had been built as a replacement for a dilapidated predecessor, following the death of bachelor John Freeman-Mitford, 1st Earl of Redesdale in 1886. The Earl, a member of the House of Lords, was a Protestant conversationalist — he published many tracts on religion pertaining to the English legal system.

On his death, he left all his estates to his distant cousin, Algernon Freeman-Mitford, grandfather of the famous Mitford sisters, who commissioned Sir Ernest George and Harold Peto to design the new hall in memory of his generous relative. The new Redesdale featured a downstairs reception room and an upstairs ballroom with a stone fireplace, balcony and small stage — exactly the sort of place Mr Epps was looking for. ‘We were a start-up, so we wanted somewhere fully down-home fashion,’ he recalls. ‘Definitely not The Ritz.’

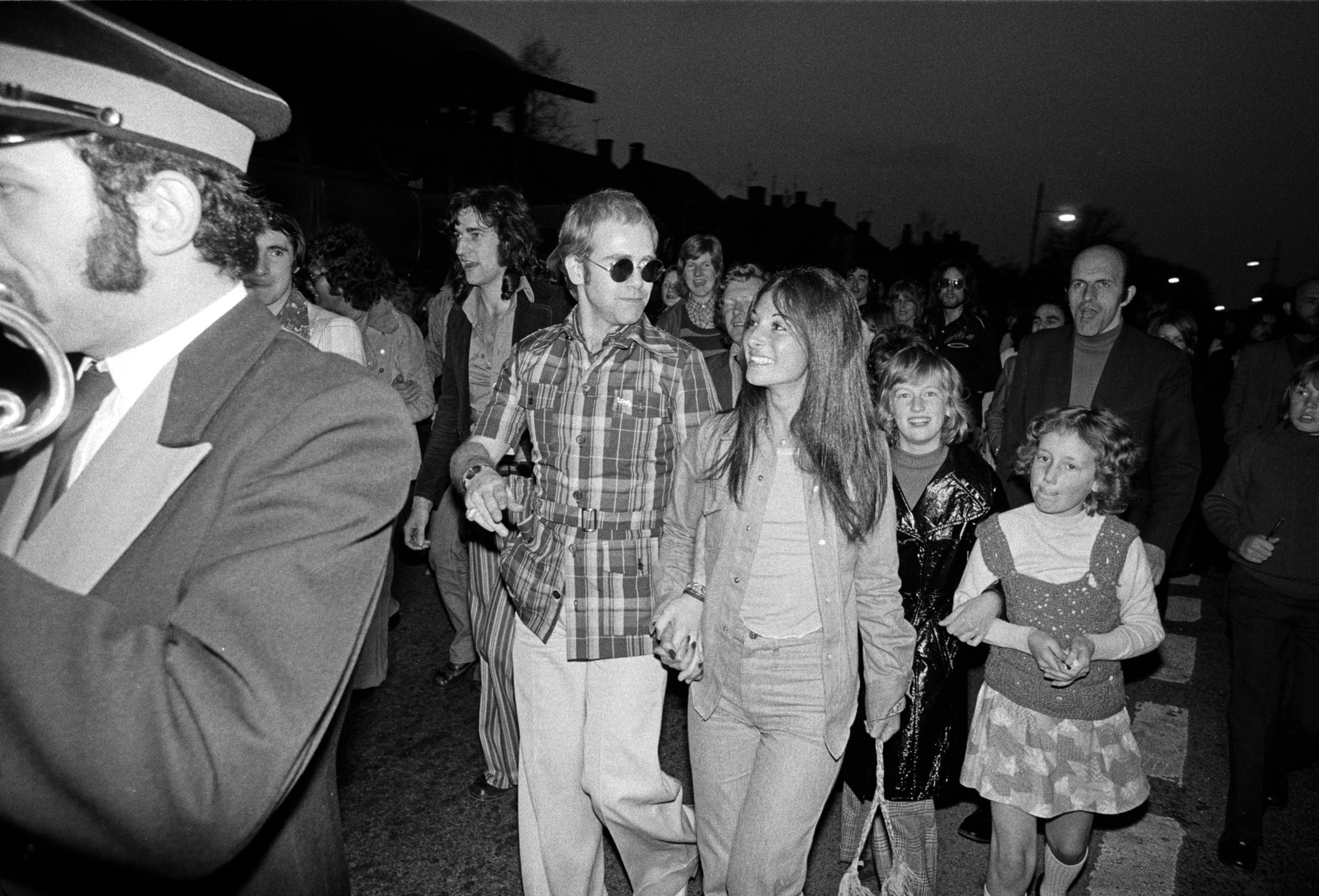

Mr Epps was not on the chartered party train from London to Moreton, having arrived at Redesdale Hall in advance to check all was in order. ‘I’d hired a local brass band and, just before the train arrived into the station, I saw the bridge over the tracks and decided that would be the best place for the band to be. What I hadn’t taken into account was that everyone coming off the train would be very merry and getting them to the hall was a little more difficult than anticipated. Elton led the parade and we marched along the street to the hall, with the band for some reason playing Hello Dolly.’

Mr Epps had arranged for a local butcher to supply sandwiches to the almost 200 guests (many more than the 120 allowed at the venue by today’s fire regulations), who were mostly movers and shakers from the music industry: radio DJs and pluggers and members of the music press, including NME, Melody Maker and Record Mirror. ‘These were the important people,’ remembers Mr Epps, ‘people who could help promote our new label and our acts.’

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The opening act on the night was Mike Silver, a folk singer from nearby Uffington, whose debut LP, Troubadour, had recently been released on Rocket. Among the other talent representing the company’s small roster at the hall was a folk rock band from the Sunderland area called Longdancer. They recorded two albums for Rocket—If It Was So Simple, in 1973, and Trailer For A Good Life, in 1974. The band split in 1976, their claim to fame being their guitarist, a ‘crazy young kid’ called Dave Stewart, who went on to form The Tourists and then Eurythmics with Annie Lennox.

Another performer was blue-eyed soul singer Kiki Dee. She had previously been signed by Sir Elton’s manager, John Reid, when he was running the British branch of Motown’s Tamla Records, and she became a Rocket mainstay. Her debut LP for her new label — her third overall — was Loving And Free, released in 1973 and featuring Sir Elton on the piano.

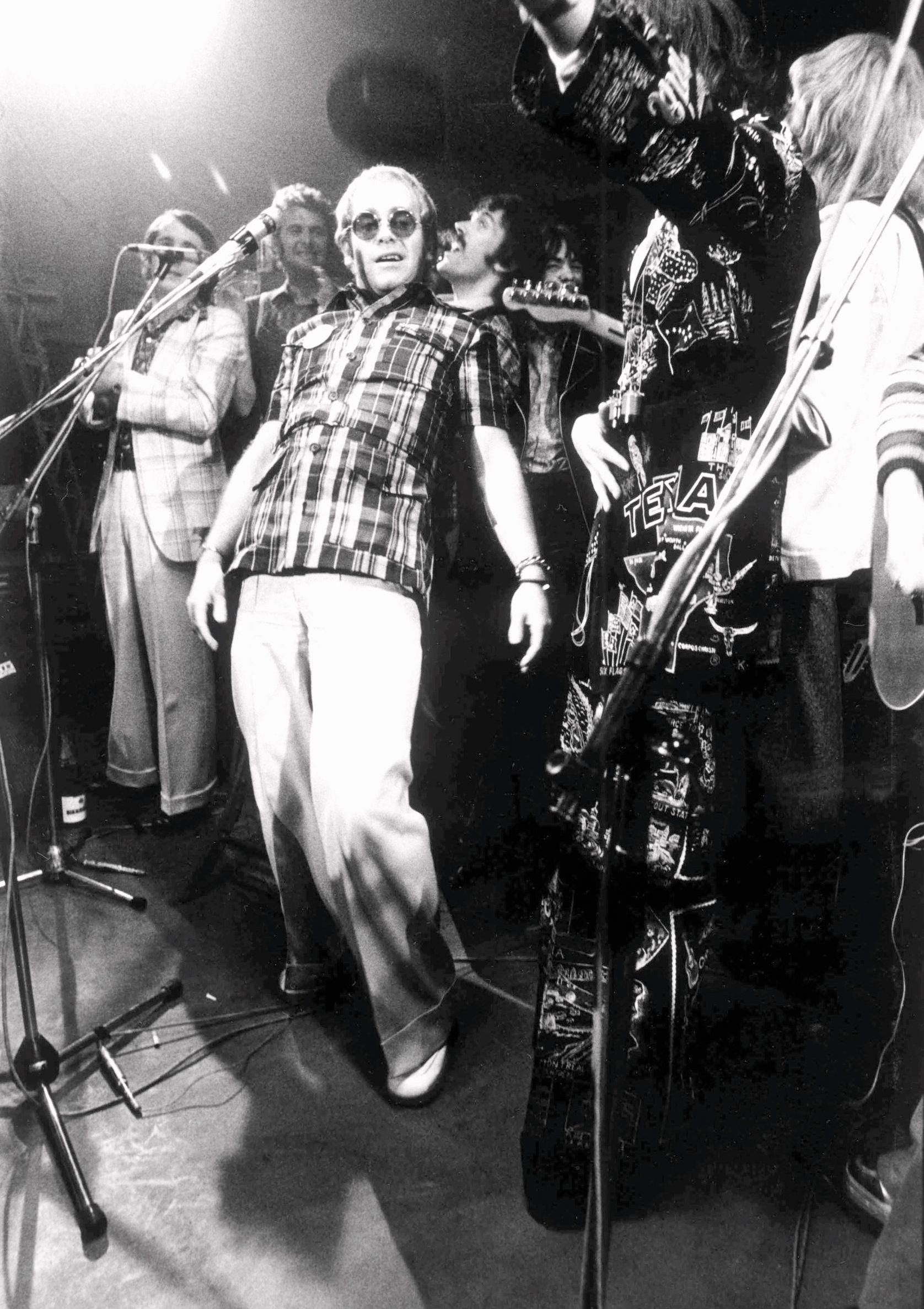

Shots by Michael Putland reveal Sir Elton rocking out in blue-streaked hair, a top hat, platform boots and checked shirt. No set list exists for the impromptu jam session, although one local lady, hired to help set up the bar and greet guests, seems to remember Sir Elton and company romping through a spirited version of the Rolling Stones’s Honky Tonk Women. Guests — and disappointed local children, who were hanging around the hall, too young to join the party — were given a goodie bag that included an 8in, seven-piece aluminium model train set with detachable carriages manufactured by German company Gebr Hildner. Also in the bag was a badge featuring the company logo, which was a smiling train designed around Sir Elton’s fondness for the Revd W. V. Awdry’s Thomas the Tank Engine.

Once the festivities wound down, the guests were shepherded onto the train back to London. Most of them, if the ones who spoke to Country Life are anything to go by, had absolutely no idea where they’d been. Sir Elton, however, cherished the memory and, some time later, purchased a 1940s painting of Redesdale by L. S. Lowry as a souvenir.

As for the fate of the label itself? ‘What we are offering,’ said Elton John in a music press interview a few weeks before his words would be reprinted as a full-page advertisement for The Rocket Recording Company, ‘is undivided love and devotion, a good royalty for the artist and a company that works its b******s off.’

When DJM demurred over guitarist Davey Johnstone’s plans for a solo LP, the singer forged ahead and created his independent label in partnership with his lyricist, Bernie Taupin, his go-to studio guy, the late Gus Dudgeon, and his manager, John Reid, through which he released Smiling Face in 1973.

Fifty years on, Sir Elton is set to retire from performing following this year’s Glastonbury Festival and former employee Stuart Epps is now a producer, running his own studio and label.

Steve Sutherland is a former editor of ‘NME’.

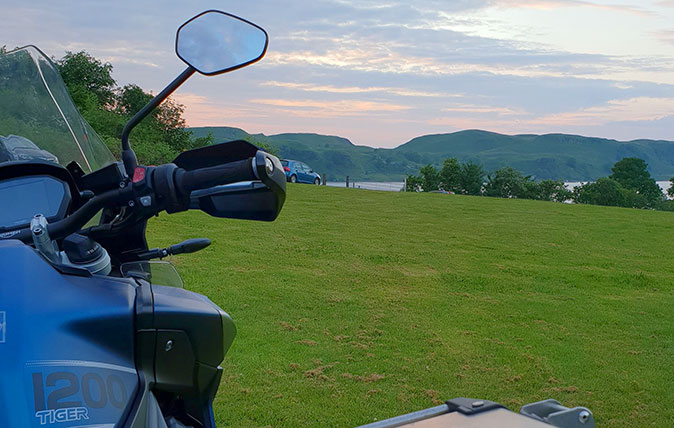

Across Scotland on a motorbike: The start of a spectacular journey

Country Life's Steve Ayres has long had a dream: to traverse Scotland on a classic British motorbike. Now, he's making

Police dogs: The fearsome law enforcers who still fit into family life

Dogs have been used for law enforcement since the Middle Ages – and the modern police often owe just as much

My favourite painting: Steve Dean

Steve Dean chooses his favourite painting for Country Life.

Greatest Recipes Ever: Stevie Parle’s cherry clafoutis

Thomasina Miers recommends Stevie Parle’s cherry clafoutis as one of her greatest recipes ever

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Alan Titchmarsh: 'It’s all too easy to become swamped by the ‘to-do’ list, but give yourself a little time to savour the moment'

Alan Titchmarsh: 'It’s all too easy to become swamped by the ‘to-do’ list, but give yourself a little time to savour the moment'Easter is a turning point in the calendar, says Alan Titchmarsh, a 'clarion call' to 'get out there and sow and plant'.

By Alan Titchmarsh

-

Rodel House: The Georgian marvel in the heart of the Outer Hebrides

Rodel House: The Georgian marvel in the heart of the Outer HebridesAn improving landlord in the Outer Hebrides created a remote Georgian house that has just undergone a stylish, but unpretentious remodelling, as Mary Miers reports. Photographs by Paul Highnam for Country Life.

By Mary Miers