The 250-year-long story of the Royal Humane Society is an incredible record of some of the bravest people ever to set foot in Britain

A teenager on his gap year who saved a boy and his father from being savaged by a crocodile is one of a host of heroic acts celebrated in a book to mark the 250th anniversary of the Royal Humane Society, says its author Rupert Uloth.

Amir Hamadamin should never have been on the A46 near Dyrham, Gloucestershire, in the early hours of a Sunday morning in March 2022. A taxi driver from Newport, he accepted a fare to Bath, way out of his usual orbit and, as a result, he almost certainly saved an old lady’s life. What he thought was a bonfire behind a café turned out to be the house next door on fire, the flames reaching the roof. After screeching to a halt, he had to run around the back after failing to gain entry by the front door and broke in using a discarded fence post to rescue a confused old lady, who spoke little English and refused to leave as she thought he was an intruder. She kept trying to return to get her dog, so he went back in with her and retrieved the pet.

For his bravery that day, Mr Hamadamin was awarded the Royal Humane Society’s Bronze medal, one of its highest awards.

The society has been rewarding ordinary citizens for saving the lives of others for 250 years and celebrates its semiquincentennial today (September 11) with a service in St Paul’s Cathedral attended by the Duke and Duchess of Gloucester, representing its royal patron The King and its president, Princess Alexandra.

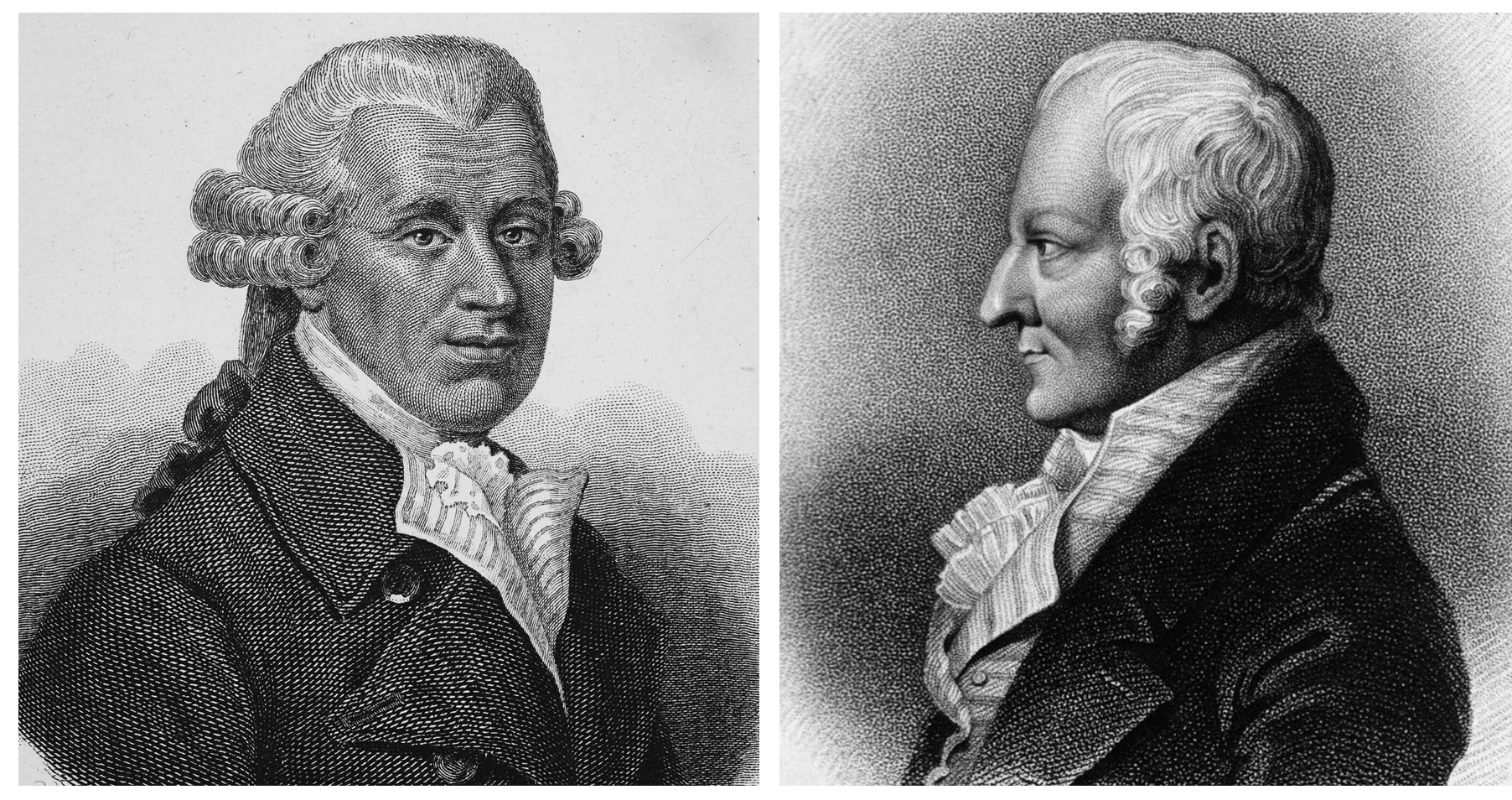

The society was founded in 1774 by two enterprising doctors, William Hawes and Thomas Cogan, eminent physicians who had become acutely aware how people were being dragged from the Thames, then dying from the effects of drowning because of the ignorance around resuscitation; its initial name was ‘The Institution for affording immediate relief to persons apparently dead from drowning’. The first meeting was held at the Chapter Coffee House in St Paul’s Churchyard, in the City of London, near where many sailors, porters and merchants were working on the banks of the Thames. The Lord Mayor of London became the society’s first president.

With supporters such as Quaker physician John Coakley Lettsom, writer Oliver Gold-smith and actor David Garrick, the society set about spreading knowledge of life-saving methods. Some were embraced, but quickly discarded. Attempting to reinflate the lungs by using bellows via the rectum, for instance, was soon recognised as ineffective. As time went on, expertise learnt from places such as the Low Countries (where breached dykes regularly led to near drownings) was adopted.

The society also employed men to patrol the banks of the Thames. Promises of reward were refined when it became apparent that vagrants were teaming up with one another so that one would throw himself in the river for another to ‘rescue’ him, then splitting the reward. In the 19th century, there was a drive to build ‘receiving houses’, permanent buildings where those in a bad way could be brought to be revived by a trained medic who was based there to respond to emergencies.

One of the best examples was a fine neo-Classical Georgian building beside the Serpentine in Hyde Park. In Victorian times, the city’s lakes were popular with swimmers in the summer and skaters in the winter, but people regularly found themselves in difficulty. The Regent’s Park skating disaster of 1867 saw 40 people die after 200 people were pitched in when the ice broke.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

London was where the society started, yet its influence soon stretched across the Empire. Eligibility embraced all British subjects and, even today, those in Sri Lanka, Australia, Canada and New Zealand are put forward for the highest award. Stories cover a wide range of highly dangerous situations requiring quick thinking, determination and incredible bravery by those going to the rescue, often of people they have never met.

Incidents include people saving sailors swept overboard mid ocean, a boy and his father being savaged by a crocodile before being rescued by a teenager on his gap year, a bystander confronting a sword-wielding terrorist and a man leading more than 60 passengers to safety from a burning coach.

What is it that makes people act in this way? It’s a question that even they cannot answer sometimes, but the instinct to save the lives of others, even if completely unknown to them, is a strong one and more than 200,000 people have been rewarded by the society.

I have had the privilege of meeting some of them in recent years. It always strikes me how modest they are, often claiming ‘anyone would have done the same thing’ in their position.

I’m not so sure. Their actions always beg the question: ‘What would you do in the same situation?’

The truth is none of us really knows unless we have been tested, but we remain fascinated by what these people have done and we hope we would act as heroically.

Trained professionals in life saving and the military have their own systems of rewards, but it is uplifting that most of those who perform such selfless acts are ‘ordinary people’. As Lloyd Bishop, who saved a man from a speeding train with seconds to spare, self-deprecatingly said: ‘For the first 50 years of my life, nothing happened that was at all noteworthy. Then December 22, 2019, came along.’

Emily Greenwood will be awarded the Stanhope Gold Medal, for the most meritorious case of the year, at St Paul’s. She was pushing her disabled son in his wheelchair along the coastal path at Holywell Bay in Cornwall on a cold winter’s day in January, when she saw a young boy being swept out to sea by a riptide together with his stepfather, who had rushed in to help him. They were fighting the current, becoming tired and distressed in the process. Without hesitating, she swam out through the surf, calmed them down and began towing them across the current even though the man was by then in a state of hypothermic collapse. Covering some 440yds in cold water, repeatedly struck by huge waves, there is no doubt she saved both their lives.

Thank goodness Emily was there. She, and all the people like her, deserve our gratitude, as well as our awe. After seeing the book about these extraordinary stories from the past 250 years, actor Hugh Bonneville noted: ‘Some pass by, because it’s easier, safer. Others step in, because it’s the right thing to do. This book reminds us what the best of us look like.’

The last word should be left to the society’s president, Princess Alexandra: ‘The reader cannot fail to be humbled by the extraordinary bravery, usually in the most challenging circumstances.’

The Royal Humane Society (www.royalhumanesociety.org.uk). The author’s book ‘Bravery Beyond Belief’, with stories from the 250 years of the Royal Humane Society, is out today, published by Unicorn (£30)

Curious questions: Who was the first person to receive the Victoria Cross?

Martin Fone retraces the history of the order and discovers the stories of its early recipients.

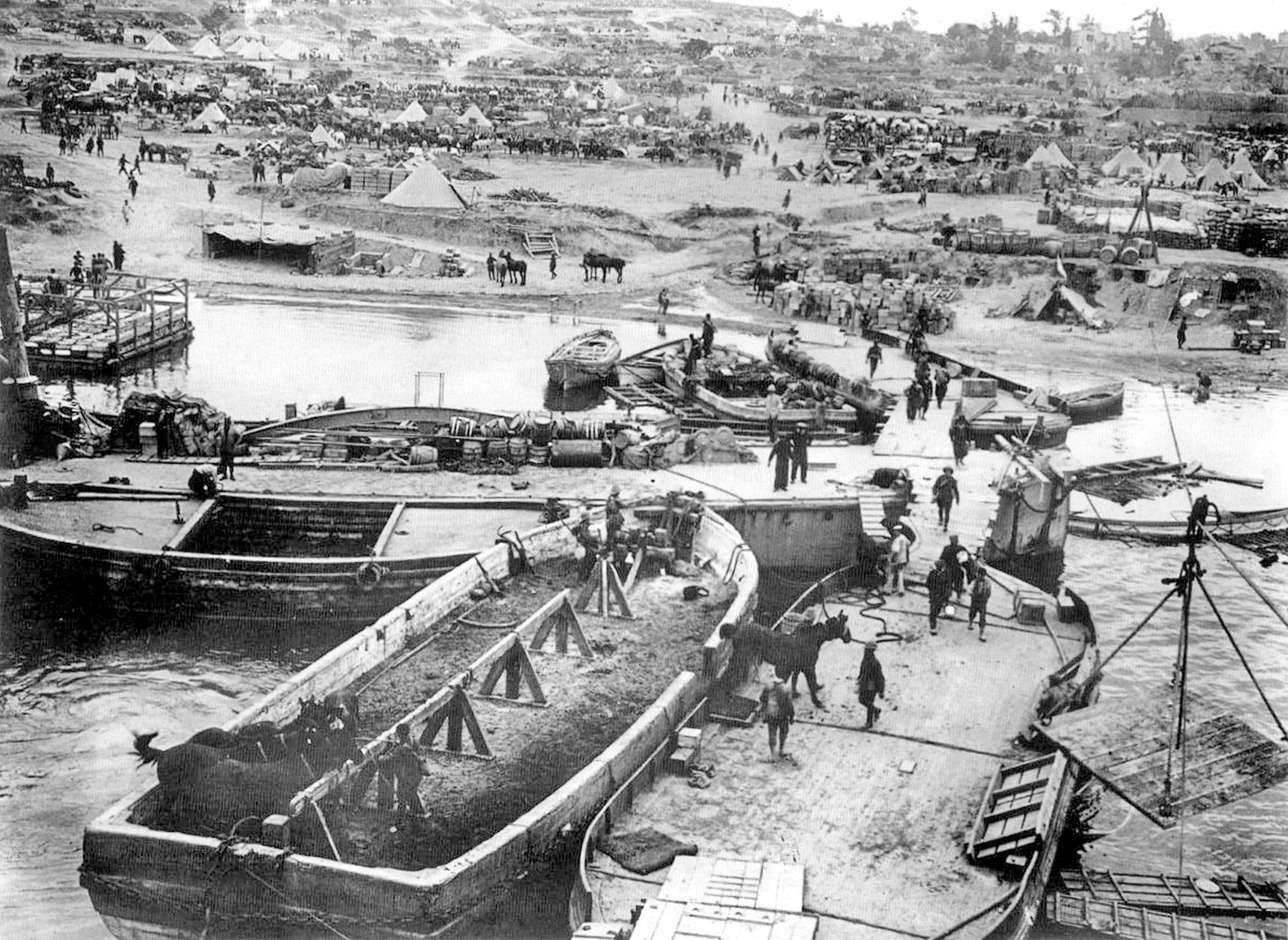

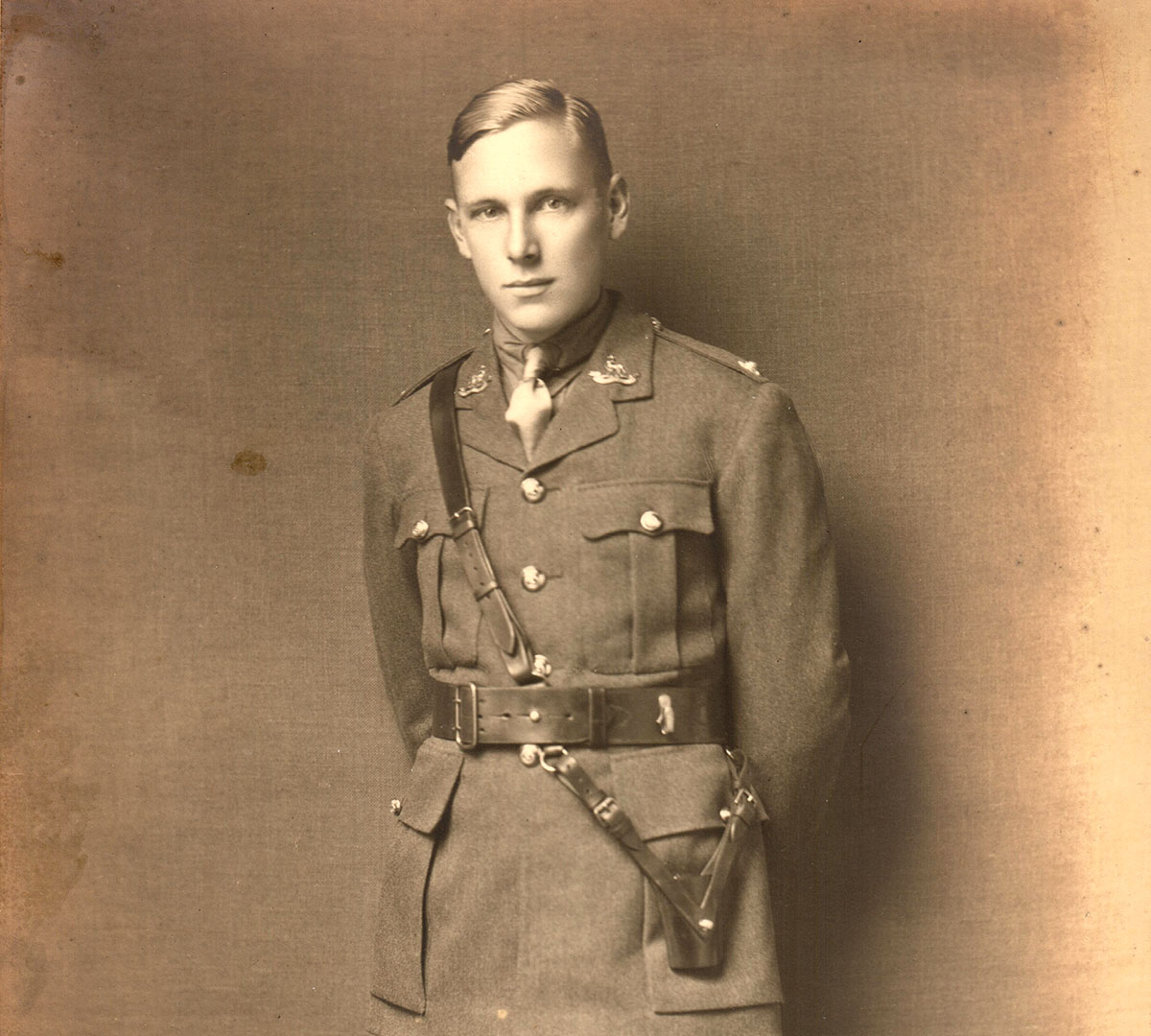

The tragic story of George Moor, the 18-year-old who won a Victoria Cross at Gallipoli and survived the Somme, only to die days before the end of the First World War

Second Lieutenant George Moor was a teenager who signed up for service at the outbreak of the First World War

The incredible tale of my father's escape from 'Italy's Colditz'

Today, we might think of spending a few months in a world heritage site in Southern Italy as an enormous