D-Day veterans in their own words: 'A lot of men did very brave things. I simply did what I was told to do'

The surviving veterans of D-Day are well into their nineties, but many still remember the events with stark clarity. Three of them spoke to Patrick Bishop and Katy Birchall; portraits by Mark Williamson.

June 6, 2024, marks the 80th anniversary of D-Day, the Allied Invasion which saw 150,000 troops from Britain, the USA, Canada and elsewhere around the world cross the English Channel in the largest scale military operation in history.

Five years ago, on the occasion of the 75th anniversary of D-Day, Country Life magazine spoke to several survivors of the assault which would prove to be the turning point of the Second World War, and the beginning of the end for the Axis Powers. Here is the article from 2019.

The tank driver: ‘You can’t really explain the horrors of what was there in France. It was just the scent of death in the air’

Among the veterans who went to Normandy for the 75th anniversary is William ‘Arthur’ Jones, who drove a Sherman tank with the Essex Yeomanry during the Battle of Normandy. In 1944, he was 18 years old; a few days after the landings, he was in the thick of the fighting, taking part in the protracted slog to take Caen. Arthur was one of many veterans taken back to France this year by the Royal British Legion (www.britishlegion.org.uk / 0808 802 8080).

‘I was young and followed instructions and had no idea of the bigger intentions.

‘What sticks in my mind is something no one can ever describe or replicate in films — the smell.

‘You can’t really explain the horrors of what was there in France. It was just the scent of death in the air.

‘There are moments I can remember very clearly, such as sleeping by the tank under canvas and being completely filthy, yet there were other periods during service I can’t recall.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

'I think there was so much overloading us at the time, we just went on autopilot.’

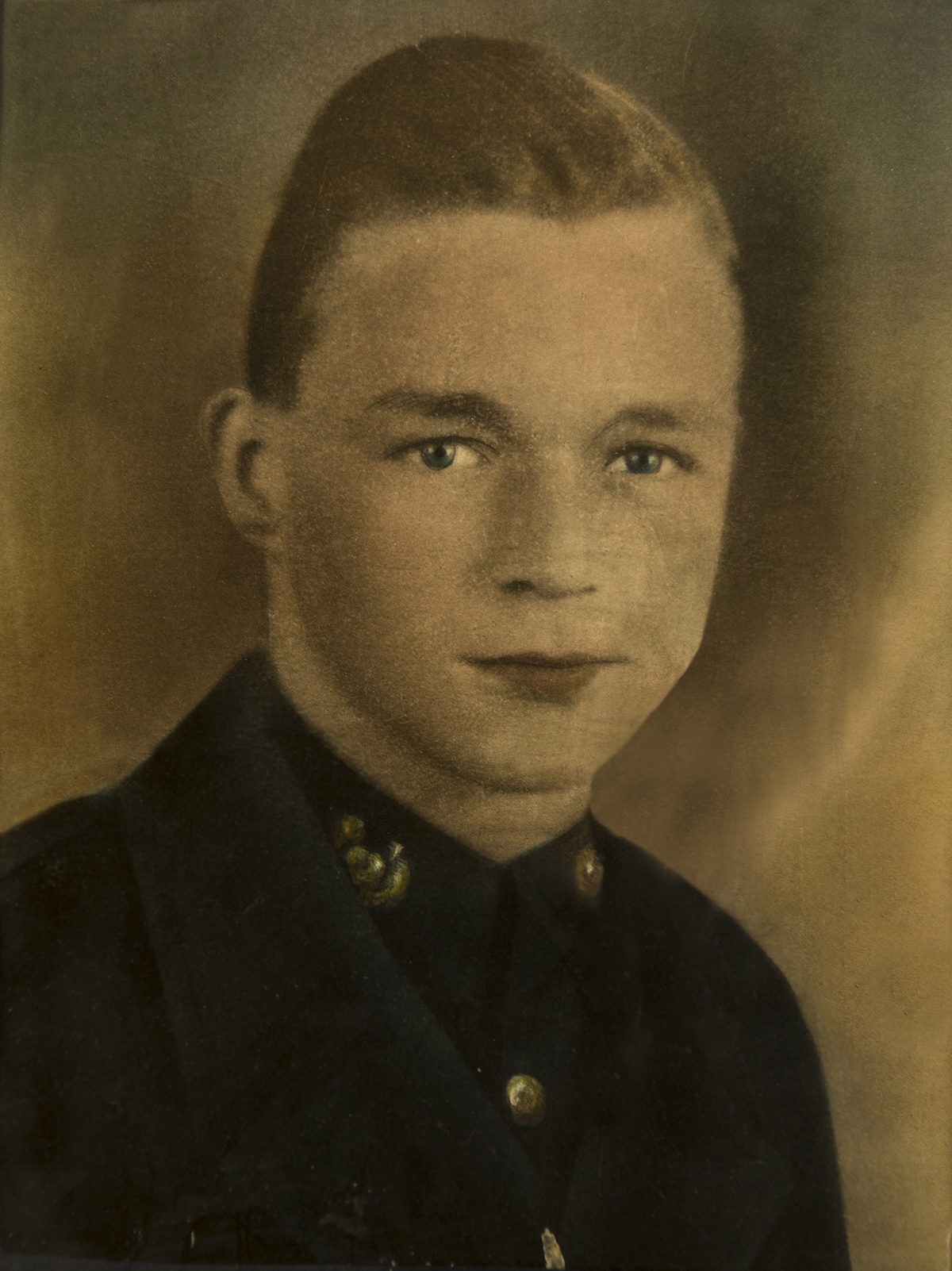

The Royal Marine: ‘A lot of men did very brave things. I simply did what I was told to do’

Eric Carter volunteered for the Royal Marines in 1941 at the age of 17. He was posted to HMS Erebus, which was deployed to join the bombardment force supporting the American landings on Utah Beach on D-Day.

‘Nobody told us anything about the plans for the landings. Up until the night of June 5, 1944, we thought we were doing a landing exercise with the Americans. Our ship, HMS Erebus, was ordered to go to Utah Beach on the western coast of France and, when we got there, we saw all these big American battleships.

‘I remember thinking: “Oh goodness, what’s going to happen here?” Suddenly, we were ordered to move into position to bombard certain targets to provide support for the American troops landing on the beach.

‘HMS Erebus was a First World War shallow draught monitor with two 15in guns on the front of her — she could go in a lot closer to the beach than the American battleships because she was flat-bottomed. As a result, our targets — big, heavy guns covering the beach where the Americans were going to land — were quite far inland. I was in the shell room that day, loading shells as fast as possible so we could make that beach secure.

‘The American troops had it rough at Utah. A lot of them were killed. I wasn’t a hero or anything like that. I was just doing my job.

‘I volunteered for the Royal Marines at 17 years old. I signed up with two of my school friends. We all wanted to sign up — we’d seen what was going on because of the Pathé newsreels showing in the cinema and we wanted to help. We were kids; it was a bit like cowboys and Indians to us.

‘We were supposed to have a year’s training in the Royal Marines, but there were so many men getting killed at sea that we only had a few months before being posted.

‘HMS Erebus was a horrible ship, really. She wasn’t designed to hold as many men as there were on board, so it was overcrowded — we all got body lice. We’d run candles down the seams of our trousers to get rid of the fleas. Then there were the cockroaches on the old water pipes, scuttling along above us. You’d sit down to have your dinner and hear a plop as a cockroach fell down into your food.

‘In the months before D-Day, we did a few landings on the French coast in small rubber dinghies at night, armed with batteries, ammunition, spare wireless parts and other supplies like that for a group of French freedom fighters. We had to look for a torch shining in the woods, sending us a signal, and head towards it, hoping that it wasn’t a German ambush.

‘It was an exciting part of the job, although when I’d climb into that little dinghy and set off, I did sometimes have a bit of a worry that I might end up in a concentration camp somewhere.

‘Years later, when I went back to Normandy, I was in a museum and met a Frenchman there who was in his nineties. It turned out that he’d been one of the Résistance fighters in the group we’d provided supplies for. It was quite something.

‘A lot of men did very brave things. I simply did what I was told to do. We wouldn’t have dreamed of disobeying orders. To us, D-Day was just another day.’

The switchboard operator: ‘It suddenly brought home the reality of everything. I thought: “My God. There are men dying on those beaches.”’

Marie Scott was a switchboard operator at the communications headquarters for the D-Day landings. She passed messages to the leaders of Operation Overlord, Gen Eisenhower and Field Marshall Montgomery and, this year, has been awarded the highest French decoration, the Légion d’honneur for her services.

‘Looking back, I believe I grew up that day.

‘I was 17 years old and a switchboard operator at Fort Southwick, passing coded messages to the troops and their commanders as they were landing on the beaches. When they lifted their lever to send their messages back to me, I could hear the gunfire. Loud, massive gunfire. It suddenly brought home the reality of everything. I thought: “My God. There are men dying on those beaches.”

‘A teenager, knowing very little of the world, on June 6, 1944, I suddenly grew up. I’d been in London since the outbreak of the war — my parents didn’t allow my sister and I to be evacuated with our separate schools as they didn’t want us split up — and so I’d grown up through the Blitz.

‘I had little education after the age of 13 because, of course, few schools remained open in London, so I got a job at 14. Later on, I took a course to become a trained General Post Office switchboard operator, which was quite prestigious at the time. I suppose that’s why the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS) allowed me to join in March 1944, even though I wasn’t quite 18.

‘I was posted to Fort Southwick in Portsmouth and, about a month before D-Day, I was given special training to operate a VHF radio. It was in its infancy then, a new one-way system where you’d throw a switch, pass your message and, when you’d finished, the recipient would pass a message back.

‘I wasn’t given much information about the invasions — no one told us a great deal — but I knew the landings had started because, using my VHF set that day, I heard the gunfire.

‘We had long shifts in those underground tunnels — in fact, I remember, at one stage, they decided we were all deficient in vitamin D, so we had to have compulsory sun-lamp treatment. We all sat there with these thick goggles on for our dose of sunshine — it was really quite hilarious.

‘Being quartered at Fareham, we were near to Southampton, where many American soldiers were based. They’d put on dances and send their trucks to pick us up. One night, I danced there to Artie Shaw’s Navy Band — not many people can say they’ve danced to that. It was fabulous, although I never quite got the hang of the jitterbug.

‘The WRNS changed my life. Many women during the war had very important jobs and I think it’s wonderful that women are being recognised for their part, too. I’m enormously proud and overwhelmed to be awarded the Légion d’honneur, but I really feel I’m accepting it on behalf of everyone at Fort Southwick. We all did our bit; we all helped to facilitate the running of Operation Overlord.

‘I was only doing my job, a tiny cog in an enormous wheel. I can’t believe I’ve received this decoration and I’m certainly not used to all this attention. It’s a tremendous honour. The other day, my grandson emailed me to say I’d gone viral on social media. I don’t really know about any of that, but he said: “Cool, Grans. Very cool.”’

The Association of Wrens: Women of the Royal Naval Services – www.wrens.org.uk

This article was originally published in June 2019.

Country Life Today: The RAF weathermen who saved D-Day and the bees who have learned to read

The story of the aircrew who gave their lives to prevent D-Day becoming a disaster, how bees are learning to

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

The designer's room: How rare, 19th-century wallpaper was repurposed inside a Grade I-listed apartment complex on London's Piccadilly

The designer's room: How rare, 19th-century wallpaper was repurposed inside a Grade I-listed apartment complex on London's PiccadillyThis home in Albany, Piccadilly, was decorated by Wendy Nicholls of Sibyl Colefax & John Fowler, as a quiet refuge in the heart of the capital.

-

The heroine's name in 'Rebecca' and a strange coffee subsitute: Country Life Quiz of the Day, May 2, 2025

The heroine's name in 'Rebecca' and a strange coffee subsitute: Country Life Quiz of the Day, May 2, 2025Friday's Quiz of the Day has a rock legend, a delicate flower and much more.

-

The heroine's name in 'Rebecca' and a strange coffee subsitute: Country Life Quiz of the Day, May 2, 2025

The heroine's name in 'Rebecca' and a strange coffee subsitute: Country Life Quiz of the Day, May 2, 2025Friday's Quiz of the Day has a rock legend, a delicate flower and much more.

-

Country Life is hiring

Country Life is hiringChange is afoot at Country Life and we are looking for a new News & Property Editor, and a Luxury Editor.

-

Britain's fastest mammal, a tropical tester and a Scottish estate: Country Life Quiz of the Day, May 1, 2025

Britain's fastest mammal, a tropical tester and a Scottish estate: Country Life Quiz of the Day, May 1, 2025Thursday's Quiz of the Day offers up a great country estate in Scotland.

-

Puffins, the world's smelliest fruit and Einstein's socks: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 30, 2025

Puffins, the world's smelliest fruit and Einstein's socks: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 30, 2025Wednesday's Quiz of the Day wonders if you know what an 'interrobang' is.

-

Lewis Hamilton, Claude Monet and the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 29, 2025

Lewis Hamilton, Claude Monet and the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 29, 2025Tuesday's Quiz of the Day looks back at Lewis Hamilton's first win and ponders on the meaning of greige.

-

Lions, country houses and the killer of a king: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 28, 2025

Lions, country houses and the killer of a king: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 28, 2025Monday's Quiz of the Day brings a beautiful Berkshire house, Macbeth and an Old Testament prophet.

-

You're having a giraffe: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 25, 2025

You're having a giraffe: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 25, 2025Friday's Quiz of the Day brings your opera, marathons and a Spanish landmark.

-

Country houses, cream teas and Baywatch: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 24, 2025

Country houses, cream teas and Baywatch: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 24, 2025Thursday's Quiz of the Day asks exactly how popular Baywatch became.