Curious Questions: What was the first ever televised sporting event?

Over 20 million people have been tuning in to watch England's stirring exploits at Euro 2020, and the huge numbers look only set to get bigger as the summer goes on. It's a far cry from the first ever televised sporting event, almost a century earlier, as Martin Fone explains.

A summer which offers both a delayed major European football championship and the Olympics is manna from heaven for television companies, allowing them to fill up vast lacunae in their schedules that would otherwise have been replete with endless repeats. Coming on top of the normal fare of sports, the armchair fan’s cup runneth over. Action is shown from every conceivable angle with slow motion replay allowing us to spot the minutiae of a piece of skill or controversy that may have eluded the naked eye. So important has sport become to all shades of the media that the global value of sports rights in 2020 was a colossal $44.6 billion in 2020 and even that marked a 12% drop from the previous year.

Sports broadcasting of a sort began at least 125 years ago when telegraphy was the quickest form of communication. On February 14, 1896, the underdogs from Winnipeg were hosted by Montreal in Ice Hockey’s Stanley Cup. In an enterprising display of initiative, the local Montreal newspaper, the Daily Star, encouraged crowds to gather at predetermined spots where they would receive up-to-the-minute game reports delivered courtesy of Canadian Pacific Railway Telegraph. News of the game was relayed to crowds in four Canadian cities, the first time that an audience was able to keep abreast with the vicissitudes of the sporting contest, almost as it happened, the 19th century equivalent of following by social media feed. The Winnipeggers heard their team pull off a shock victory.

https://youtu.be/8pjyzdBZ2bo?t=29

To celebrate its centenary in July 1898, the Evening Mail and its sister paper, the Dublin Express, reported the results of annual regatta of the Royal St George Yacht Club by employing none other than Guglielmo Marconi to send them through by radio telegraph. For the three days of the regatta, Marconi, following the competitors in a tugboat, sent over 700 messages to a land station located on Kingsdown harbour. From there they were decoded and sent by telephone to the newspapers’ offices, allowing them to steal a march on their rivals and provide readers and crowds at their offices with the latest results. The success of the enterprise cemented Marconi’s reputation as a leading figure in this form of commercial communications.

KDKA of Pittsburgh, the first commercially licensed radio station in the world to broadcast, soon found the lure of sport too hard to resist, scoring several notable firsts in 1921. It broadcast the first sporting event, a ten-round boxing match between Johnny Ray and Johnny Dundee on April 11th which ended in a draw, the first World Heavyweight Boxing Championship fight on July 2nd, in which Jack Dempsey knocked out Georges Carpentier in the fourth round, and the first professional baseball game on August 5th, the Pittsburgh Pirates beating the Phillies 8-5.

In Europe, the Irish once more led the way. Paddy Mehigan took to the airwaves on August 29, 1926, to provide a commentary on the All-Ireland Hurling Semi-Final in which Kilkenny overcame Galway. The BBC, incorporated on January 1, 1927, broadcast its first sporting event fifteen days later, the England Rugby Union team’s 11-9 victory over the Welsh at Twickenham.

Henry Wakelam provided the commentary on the BBC’s first football broadcast, a 1-1 draw between Arsenal and Sheffield United on January 22nd. Ahead of the game, the Radio Times had published a plan of the pitch divided into eight squares. As play progressed, the listener was given the square reference so that they could follow play, possibly giving birth to the phrase ‘back to square one’. The Times noted that Wakelam’s commentary was ‘notably vivid and impressive’ while The Spectator thought that that type of broadcasting had come to stay.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Indeed, it had. By the end of 1927, the most important events in Britain’s sporting calendar, including the Grand National, the Boat Race, the FA Cup Final, Wimbledon, and the Derby, had been broadcast live over the airways.

Although the public was accustomed to seeing footage from sporting events, with the Epsom Derby filmed and shown as part of a newsreel in cinemas since 1896 — never more infamously than in 1913, when Emily Davidson was trampled by the king's horse at the race as part of a Suffragette protest. But live broadcasting by television was another matter.

Following a successful demonstration of his system in May 1931, John Logie Baird mused that ‘the idea of televising the Derby or cricketers at Lord’s was not as fantastic as some imagined’. Emboldened, he obtained permission from the BBC to use their transmitters at the Epsom racecourse, although they stipulated that the Baird Company’s commentary should be run through a separate telephone line so as not to interfere with their own.

On June 2, 1931, the day before the Derby, Baird took his equipment, housed in a caravan, to the racecourse and sent pictures of one of the minor races to his company’s offices in London’s Long Acre, where they were viewed on four sets. The outlines of the horses were visible but blurry and they hoped for better results the next day.

On race day, the caravan was positioned opposite the winning post with wooden scaffolding around it, which members of the public, to the engineers’ dismay, thought was a temporary viewing platform for their use. Baird’s plans created a stir, the Daily Herald noting that ‘it is hoped, for the first time in history, that tomorrow the Epsom Derby will be broadcast through the magic eye of the Baird televisor, and the result of the race will be seen by hundreds of viewers’.

Rather than hundreds some 5,000 viewers saw what by modern standards were very low-resolution pictures, just thirty lines of television, largely consisting of flickering representations of the crowd, the parade of horses, and Cameronian winning the race. Pictures were fed to the Baird offices where a crowd of journalists had assembled and then relayed throughout the land by the BBC with their own commentary. It was an impressive audience given that televisors were beyond the reach of most pockets, costing £26 ready assembled and £18 in kit form.

Reactions were positive. The Falkirk Herald, although complaining of the flickering pictures and the interference, noted that ‘the course itself, with its crowds and marquees was easily identified, and the flying scud of horses…conveyed something of the thrill of the real thing’. Mr Willis from Norwich wrote that he could ‘see the horses flash past the screen. This experiment was little short of sensational’, while Worthing’s Mr Lamb exclaimed that ‘of all the recent developments in television the broadcast of the Derby was, to my mind, the most wonderful’.

Baird may have put live broadcasting on the map, but by 1937 his pioneering system had been eclipsed by Marconi/EMI’s superior technology.

The Americans had to wait until May 17, 1939, to see a live sporting event, a college baseball game between the Columbia Lions and Princeton Tigers broadcast by NBC. Action replays were first used in a broadcast of the American Football game in which the Navy beat the Army 21-15 on December 7, 1963. When Army quarterback, Rollie Stichweh’s touchdown was repeated, viewers inundated the switchboard to enquire whether he had scored again.

Sports broadcasting has come a long way.

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.

-

How an app can make you fall in love with nature, with Melissa Harrison

How an app can make you fall in love with nature, with Melissa HarrisonThe novelist, children's author and nature writer Melissa Harrison joins the podcast to talk about her love of the natural world and her new app, Encounter.

By James Fisher

-

'There is nothing like it on this side of Arcadia': Hampshire's Grange Festival is making radical changes ahead of the 2025 country-house opera season

'There is nothing like it on this side of Arcadia': Hampshire's Grange Festival is making radical changes ahead of the 2025 country-house opera seasonBy Annunciata Elwes

-

Curious Questions: Why do we carve pumpkins at Halloween?

Curious Questions: Why do we carve pumpkins at Halloween?The devilishly smiling image of Jack O'Lantern is inseparable from Halloween, but what's the story behind it? Martin Fone explains — and discovers that the festival many complain about as an American import has been this side of the Atlantic for centuries.

By Martin Fone

-

Who was the real St Crispin, and what did he have to do with the Battle of Agincourt?

Who was the real St Crispin, and what did he have to do with the Battle of Agincourt?You have questions about Shakespeare's most famous speech. We have answers.

By Ian Morton

-

Do you know your apple-catchers from your tittamatorter? Take a crash course in the UK's local languages

Do you know your apple-catchers from your tittamatorter? Take a crash course in the UK's local languagesWith experts warning that regional accents could disappear within decades, our sometimes quaint and, often, bizarre dialect words are becoming ever-more precious.

By Victoria Marston

-

Curious Questions: Why do barristers and judges wear wigs?

Curious Questions: Why do barristers and judges wear wigs?Like marmalade on toast, saying sorry and the Shipping Forecast, there are few things more typically British than the courtroom wig. Agnes Stamp explains why our barristers and judges wear them.

By Agnes Stamp

-

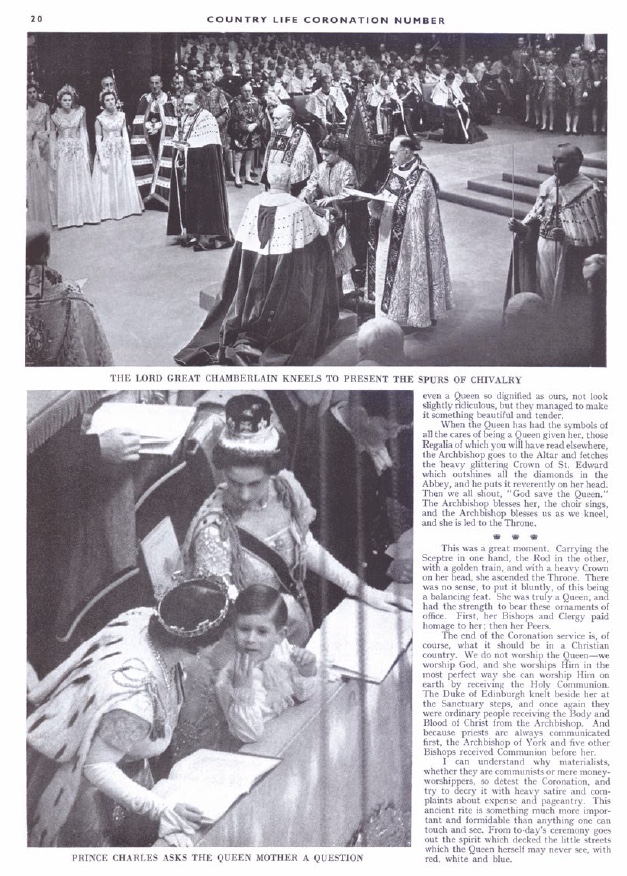

What it's like to have a prime seat at a Royal Coronation by John Betjeman, who reported for Country Life in 1953

What it's like to have a prime seat at a Royal Coronation by John Betjeman, who reported for Country Life in 1953The late, great Poet Laureate John Betjeman was among the congregation when Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II was crowned in 1953 — and he wrote about it for Country Life. We're very proud to reproduce that article now — The Queen's Coronation: In The Abbey by John Betjeman.

By John Betjeman

-

Curious questions: Did the modern Olympics really start in Much Wenlock?

Curious questions: Did the modern Olympics really start in Much Wenlock?Martin Fone traces the history of the Olympics and examines the contribution of Shropshire doctor William Penny Brookes.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Is the chocolate side really the top of a Jaffa Cake?

Curious Questions: Is the chocolate side really the top of a Jaffa Cake?Martin Fone discovers nothing is quite as it seems in the world of Jaffa Cakes — including whether they are a biscuit or a cake or whether chocolate sits at the top.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Question: When was the first census held?

Curious Question: When was the first census held?As the UK prepares to compile this decade's census, Martin Fone retraces its history.

By Martin Fone