Country Life Today: How living near a top state school can more than double the price of your home

Today, we dig into research about houses and schools, take a look at dogs of days gone by and look at some very pricey whisky.

How the best state schools in Britain can more than double house prices

It's long been established that house prices in the catchment areas for good schools are higher than average; this weekend, The Sunday Times ran an interesting analysis using data from Savills of exactly how much extra some people pay.

'The attraction of a place at one of the best state non-selective schools is reflected in the price of homes in the vicinity,' the report explains. 'Our research found that, on average, properties within a 1.25-mile radius of these schools cost £133,000 more than other homes in the same local authority.'

Top of the list is Durham Johnston school, where properties in catchment apparently cost over 120% more. The report also looked at extra costs of property compared to paying school fees of £15,000 a year, with some surprising results. One example claims that 'homes close to Silverdale in Sheffield are £162,851 pricier on average than those in the surrounding area — equivalent to 17 years of private education for one child.'

Statistical analysis like this throws up all sorts of questions. Are the houses and areas being compared really like-for-like, in a meaningful way? If you buy the house - rather than pay for the fees - don't you get the money back eventually? And what happens if the school in question nosedives in quality? Regardless, it's certainly food for thought.

The dogs that disappeared

If you missed this at the weekend, put it right now: Patrick Galbraith's piece on the breeds of yesteryear which no longer exist is fascinating, and a salutary warning.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Another reason to look out for ticks

Doctors are urging anyone working or walking in the countryside, particularly in Scotland, to protect themselves from ticks following the discovery that the insects carry a parasite, previously unseen in the UK.

University of Glasgow scientists found the tick-borne organism in ‘a large number’ of sheep in the North of Scotland. Common in other countries, the parasite can infect humans, with potentially serious consequences if the disease is untreated.

Where’s the world most valuable whisky collection?

If you guessed Scotland, Ireland or, at worst, Tennessee, you’d be wrong. The world’s greatest whisky collection is in Vietnam, according to the Guinness World Records. It belongs to a Vietnamese businessman, Viet Nguyen Dinh Tuan, and contains 535 extraordinarily sought-after vintage bottles — including three Macallan Fine & Rare from 1926 (by way of a comparison, a single Macallan 1926 was sold at auction for £1.5 million).

‘Whisky collecting has been my life's passion,’ Mr Viet explains. ‘Every spare I moment I get, I'm searching auction sites and trading websites to find famous and rare whiskies from around the world.’

When finders is not keepers

The conviction of two metal detectorists who stole an early-medieval hoard worth £3 million has shone the spotlight on treasure theft and how the concealment of important artefacts deprives the nation of its heritage.

The good news, however, is that there are fewer instances of people hiding their findings, according to expert Robert Falkiner, who sits on the Treasure Valuation Committee that works out rewards for finders. ‘[It] is considerably rarer now than it was 25 years ago.’

On this day… in 1487

Elizabeth of York was crowned Queen of England. The daughter of Edward IV, she helped put an end to the War of the Roses when she married Henry Tudor, who had defeated her uncle Richard III, the last Yorkist king, in the Battle of Bosworth Field.

The two married in 1586 but Elizabeth wasn’t crowned until November 25 of the following year, long after she had given birth to their first son, Arthur. Henry had been crowned alone in 1485, before their marriage—it was his way of showing that he was claiming the title of king by right of conquest rather than by marrying the Yorkist heiress.

'Climate emergency' named as the Oxford Word of the Year for 2019

The growing sense that the planet is on the verge of a climate catastrophe has taken over our language. Virtually all the terms that the Oxford Dictionaries shortlisted for their Word of the Year 2019 have something to do with rising temperatures and extreme weather, from climate crisis to ecocide and the imported ‘flight shame’.

But the phrase that has most become part of our everyday discourse is climate emergency, which is now more than a hundred times more common than it was just twelve months ago.

It’s this term, more than any other that captures ‘the demonstrable escalation in the language people are using to articulate information and ideas concerning the climate,’ according to the Oxford linguists.

And finally…

Pictures that are literally out of this world.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Burberry, Jess Wheeler and The Courtauld: Everything you need to know about London Craft Week 2025

Burberry, Jess Wheeler and The Courtauld: Everything you need to know about London Craft Week 2025With more than 400 exhibits and events dotted around the capital, and everything from dollshouse's to tutu making, there is something for everyone at the festival, which runs from May 12-18.

By Lotte Brundle

-

Everything you need to know about private jet travel and 10 rules to fly by

Everything you need to know about private jet travel and 10 rules to fly byDespite the monetary and environmental cost, the UK can now claim to be the private jet capital of Europe.

By Simon Mills

-

The brilliant tractor tribute to the NHS from a group of Warwickshire farmers

The brilliant tractor tribute to the NHS from a group of Warwickshire farmersPeople around Britain have been paying tribute to the efforts of our NHS workers at the time of the coronavirus pandemic — but few have been as creative and clever as this one.

By Toby Keel

-

London's iconic red bus at risk and 6,000 year old chewing gum gives clues into our DNA history

London's iconic red bus at risk and 6,000 year old chewing gum gives clues into our DNA historyCuts to industry subsidies and an increase in fares has left bus use at its lowest point ever, while DNA extracted from ancient 'chewing gum' allows scientists to decipher the genetic code of a Stone Age woman.

By Alexandra Fraser

-

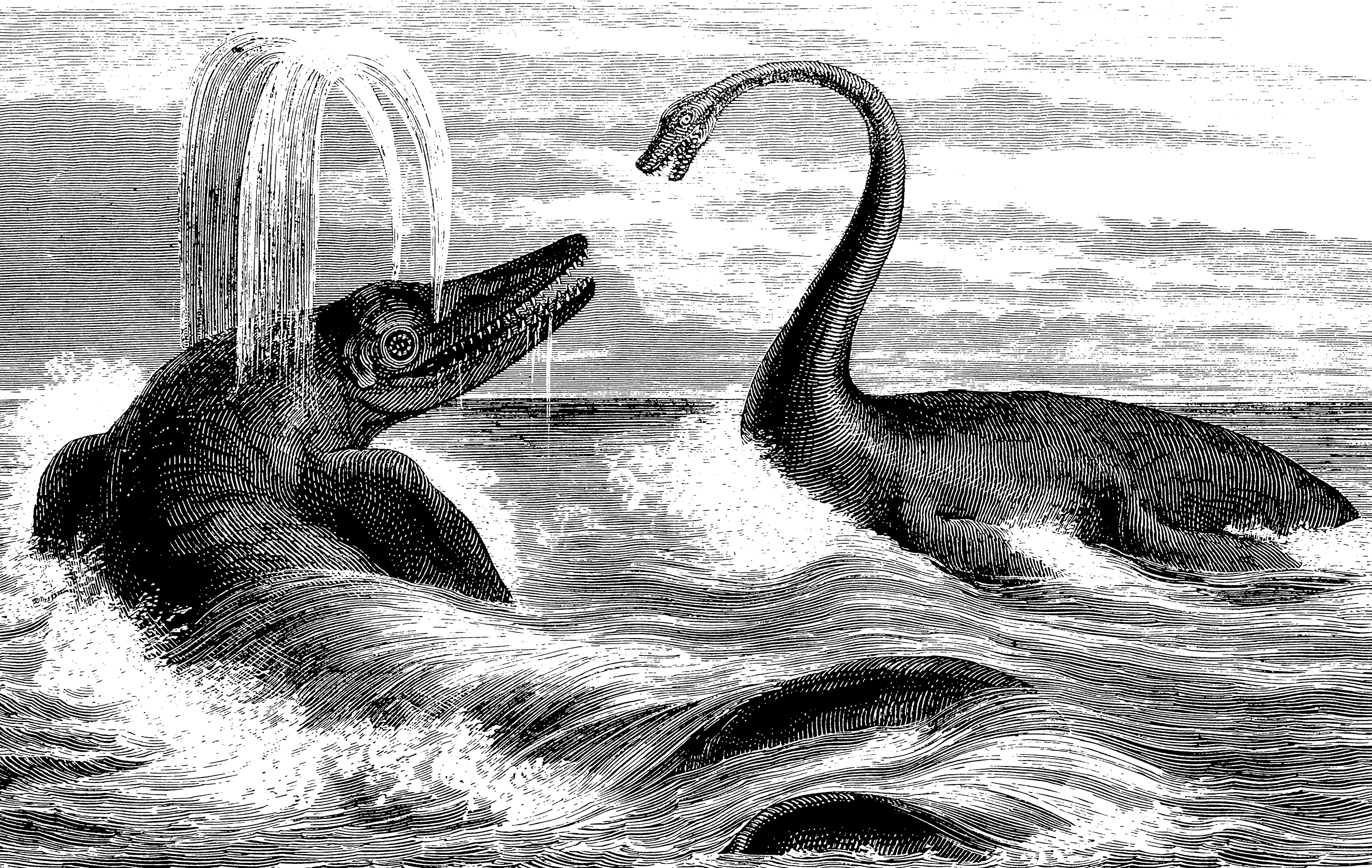

90-million-year-old 'swimming dinosaur' skeleton found by dogs out walking in Somerset, and the nonchalant moths who don't bother fleeing enemies

90-million-year-old 'swimming dinosaur' skeleton found by dogs out walking in Somerset, and the nonchalant moths who don't bother fleeing enemiesA superbly intact dinosaur skeleton — described as being 'museum quality' — has been discovered on a beach in Somerset.

By Toby Keel

-

Battle to ban 4x4s from the idyllic Lake District spot bequeathed by Beatrix Potter, eagle fights octopus and the 'snail's pace' climate talks

Battle to ban 4x4s from the idyllic Lake District spot bequeathed by Beatrix Potter, eagle fights octopus and the 'snail's pace' climate talksThis morning we look at Little Langdale's fight for peace, reflect on the climate change talks in Madrid and discover the soundtrack for Brexit.

By Toby Keel

-

Country Life Today: How Greta Thunberg shifted the dial on climate change — and the backlash shows just how much

Country Life Today: How Greta Thunberg shifted the dial on climate change — and the backlash shows just how muchThis morning we ponder whether Greta Thunberg is the Joan of Arc for the environmental movement, look at a key election — one from 19 years ago — and ponder the marvel of 'dad tidying'.

By Toby Keel

-

Country Life Today: Great news for those who love our great country pubs — the years of decline are over

Country Life Today: Great news for those who love our great country pubs — the years of decline are overThere is a great sign of health in the pub industry, we look back at Edward VIII's abdication message and fret about Greenland's melting ice.

By Toby Keel

-

Country Life Today: Spain accused of being 'a deplorable choice' for UN climate conference

Country Life Today: Spain accused of being 'a deplorable choice' for UN climate conferenceA no-holds-barred assault on the Spanish fishing industry, Banksy raising awareness of the homeless and the woes of the Christmas jumper are in today's news round-up.

By Carla Passino

-

Country Life Today: 'This is perhaps the ultimate wake-up call from the uncontrolled experiment humanity is unleashing on the world’s oceans'

Country Life Today: 'This is perhaps the ultimate wake-up call from the uncontrolled experiment humanity is unleashing on the world’s oceans'In today's round up, we examine why oxygen loss is putting oceans at risk, discover that action to cut air pollution brings almost immediate benefits to human health and find out which bird's arrival marks the start of winter in Gloucestershire.

By Carla Passino