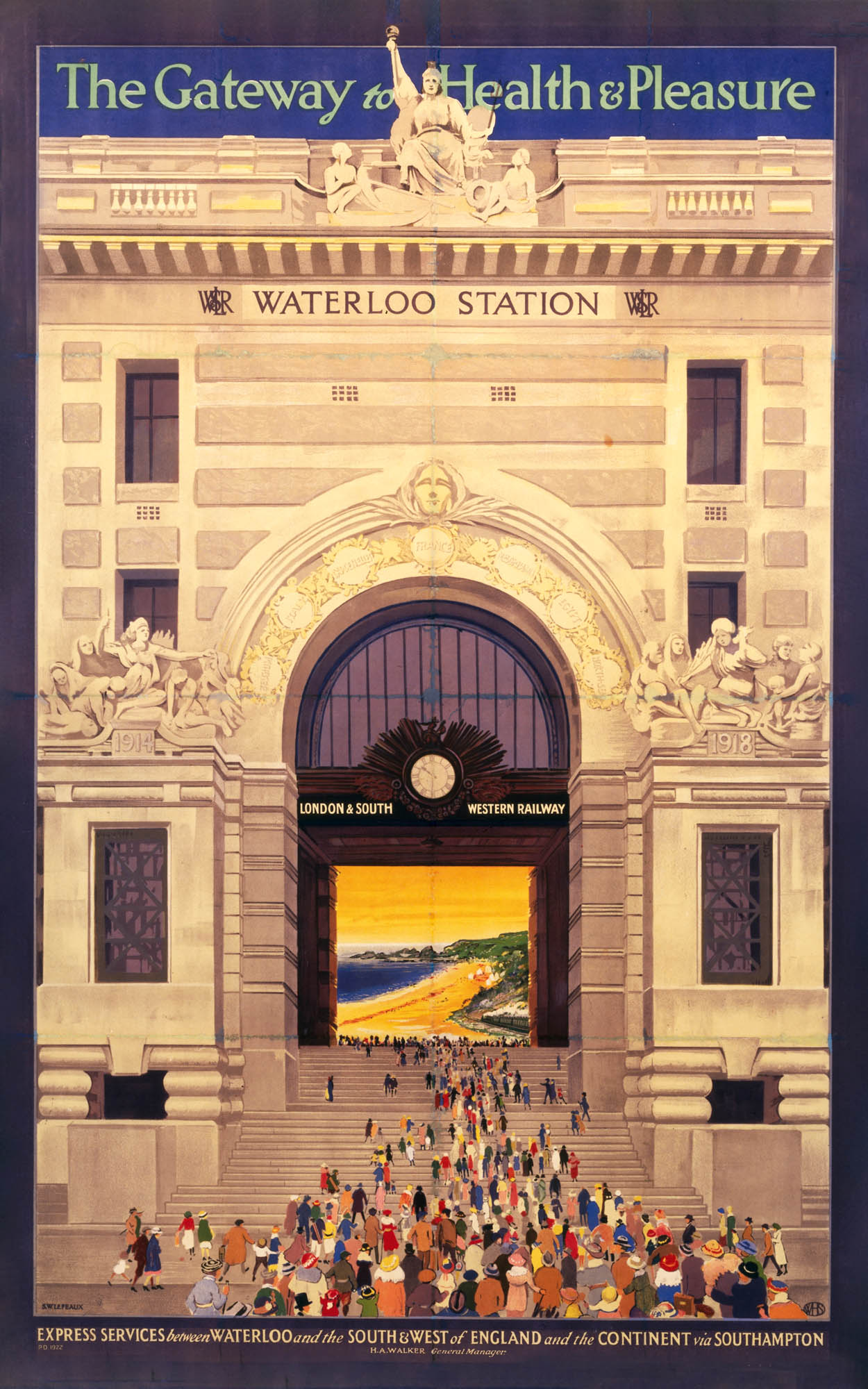

175 years of London Waterloo: 'The gateway to everything that’s wonderful'

As commuters dash to catch their train home from south London and lovers meet under its giant clock, Julie Harding explores Waterloo — Britain’s busiest railway station — on the eve of its 175th anniversary.

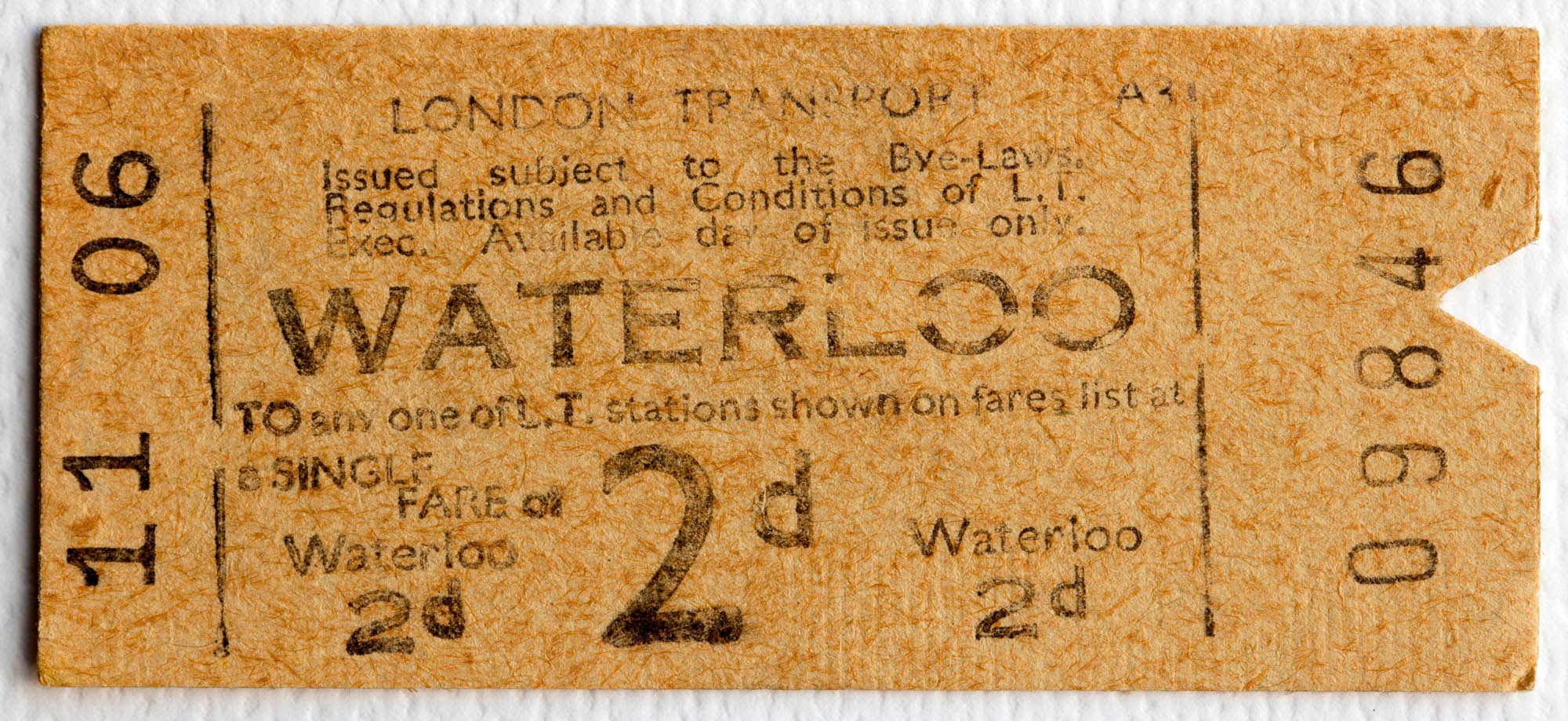

We meet under the giant clock opposite platform 12. The four-faced timepiece, made by Gents of Leicester, has hung above the concourse of London’s Waterloo Station for 101 years, presiding over perhaps more than a million rendezvous, even secret romantic trysts, in that time.

Where else would you arrange an encounter but at Britain’s busiest railway station, where today — an ‘unexceptional’ Thursday in late spring (as in, there have been no major disruptions, such as signalling issues or fires on the line) — 225,000 workers, tourists, shoppers, theatregoers and fun-seekers will pass through the ticket gates either bound for the capital or England’s South-West?

Rachel Kolsky, historian, author, prize-winning guide and self-confessed ‘natterer’, was here just before the clock’s colossal metal hands signalled 2.30pm (or 14.30 in railway parlance). Ms Kolsky has eschewed the umbrella, however — that prop favoured by myriad tour guides — and instead sports a green tote bag slung over one shoulder, out of which peep bright pink and yellow felt flowers, arresting and conspicuous enough to enable any new followers swiftly to pick her out from the crowd. The tour, which is set to highlight facts and features of this station as it celebrates its 175th birthday on July 11, will last only 90 minutes, so time is of the essence.

‘I love trains and I Inter-railed three times as a student. Waterloo is my absolute favourite station, however. There’s something very special about it,’ admits Ms Kolsky, in words not only imbued with hefty enthusiasm, but also delivered with considerable rapidity.

‘For me, it’s the gateway to everything that’s wonderful; perhaps going to the South Bank and visiting the National Film Theatre or seeing a production at the Old or Young Vic.’

Five facts about Waterloo Station

- Fewer people are travelling by train since covid. In 2019, Waterloo welcomed 98 million passengers, but that has now fallen to about 41 million per annum. That still makes it the busiest railway station in the country, by number of passengers who start or finish their journeys here. (Clapham Junction, a couple of miles south, handles more trains and interchanges since it also funnels trains to London Victoria.)

- Despite the irony of trains heading to France and the Continent from a terminus named after the site of a great British (and Prussian) victory over the French, Eurostar services ran for a total of 13 years from 1994 before switching to St Pancras International

- The News Theatre cinema operated between 1934 and 1970 at the Westminster Bridge Road end of the station and was demolished in 1988

- Many movies have been filmed here, including The Bourne Ultimatum, Alfie (featuring Michael Caine) and Waterloo Bridge

- Plans are afoot to improve Waterloo Station further, with roof glazing being renewed, and Lambeth Council’s redevelopment plans for Elizabeth House will mean a transformed pedestrian approach to Victory Arch that will finally give it the wow factor it deserves

Waterloo is certainly a station for the 2020s. Its once slightly cluttered, dingy concourse, 770ft long, 120ft wide and filled with inconveniently placed retail outlets, covered stairwells and even a road (under the clock, incidentally) that led to luggage-laden passengers from the ocean liners and boat trains arriving from Southampton, has been transformed in recent times.

Today, it is a cavernous, largely uninterrupted bright space, enabling the tardy commuter or holiday-maker to dash towards their on-time train unimpeded — except by fellow human beings. The station teems with life, even between and beyond rush hours, the constant din and hubbub — punctuated frequently by amplified train announcements — not unlike a lively pub on a Saturday night.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

‘Waterloo isn’t only a commuter station, it’s one of London’s most beautiful stations,’ continues Ms Kolsky. ‘You also regularly see sights here, such as people off to Wimbledon or Ladies Day at Royal Ascot, burly rugby players bound for varsity matches at Twickenham; and it was one of the hubs for the UEFA European Women’s Championship football. No other station has Waterloo’s sense of occasion.’

Two centuries ago, the area hadn’t yet played host to a single locomotive, but 17th- and 18th-century hedonists had flocked to the spot in transport pulled by a more basic kind of horse-power. Lambeth Marsh was the home of Cuper’s (or Cupid’s) Pleasure Gardens, which boasted walks, bowling greens, musical entertainment, food and wine and firework displays. Light industry proliferated, too, with evidence of a brewery and a timber yard surviving.

When Nine Elms Station, original terminus of the London and South Western Railway, designed by Sir William Tite in the neo-Classical style and opened in 1838, was deemed too far from the City, the land around the long-closed Cuper’s Gardens was earmarked for the new Waterloo Bridge Station, despite its boggy proclivity. Engineers proceeded to construct a network of arches on which the constantly evolving terminus has rested for the entirety of its existence. With space in short supply, up until the mid 20th century, this subterranean world was a hive of frenetic activity, with bustling offices, a typing pool and luggage facilities, as well as bars, games rooms and even a rifle-firing range for staff. One room was fortified for government document storage during the First World War and another area doubled as an air-raid shelter for escape from the Luftwaffe’s bombs.

Prolific architect Tite was once again called upon to design the new station, which opened in 1848 with only six platforms and the intention of it being merely a stop en route to a City terminus.

Evolution into a final destination was so haphazard that, by the end of the 19th century, the station had 18 platforms, but only 10 numbers, and it had become a figure of fun. Jerome K. Jerome wrote in Three Men in a Boat: ‘We got to Waterloo at 11, and asked where the eleven-five started from. Of course nobody knew; nobody at Waterloo ever does know where a train is going to start from, or where a train when it does start is going, or anything about it.’

Cem Davis, station manager, who began working here 21 years ago, aged 18, presides over a very different beast today; one where there are 24 platforms and trains whose unmistakable destinations are displayed on giant live digital departure boards, as well as via mobile devices.

Disruption is Mr Davis’s bête noire. ‘The concourse can fill up pretty quickly due to all the ways people can get into Waterloo, so we provide real-time information. We have to be on our game,’ he says. Mr Davis commutes from Kent, arrives at Waterloo East (opened in 1869 as Waterloo Junction), heads along the above-ground walkway across the shiny cream-tiled main concourse and into his office that overlooks the platforms.

Coronation day was an obvious career highlight. ‘We had more than 5,000 military personnel coming into Waterloo on nine trains in the largest movement of troops since Sir Winston Churchill’s funeral,’ reveals Mr Davis. ‘They marched across the concourse en route to the Mall. To plan and witness that was one of a kind, but it also occurred as we were operating a normal train service, so it was a challenge.’

Back on the tour, Ms Kolsky heads variously to the eclectic artworks and memorials for a closer look. ‘This really is like a public art gallery,’ she observes, when standing beside Peter Laszlo Peri’s The Sunbathers, commissioned for the Festival of Britain and then thought ‘lost’ until tracked down, in a forlorn state, in the garden of the Clarendon Hotel in Blackheath. A crowdfunding campaign by Historic England saw it restored to its former glory. In 1922, when the station’s most significant redesign was complete and J. R. Scott’s grand Portland stone Victory Arch formed the new main entrance, memorials to the company’s employees killed in the First World War were erected here in what Ms Kolsky terms the station’s ‘sad spot’. Not far away, Basil Watson’s National Windrush Monument — a family trio standing atop their luggage and signalling not only a new start for them, but also for a beleaguered post-war Britain in need of a rebuild — has drawn quite a crowd. Small children climb on the bronze suitcases.

Back under the Gents of Leicester clock, the tour sadly over, Ms Kolsky proffers one final, more frivolous fact. ‘Of course, you probably know that this area of Waterloo Station was the location of the first meeting between Del Boy and Raquel in Only Fools and Horses,’ she notes with a wide smile, before turning on her high suede heels and hot-footing it to the Tube for her journey home. Just one more of the many romances that started under the clock at this exceptional station.

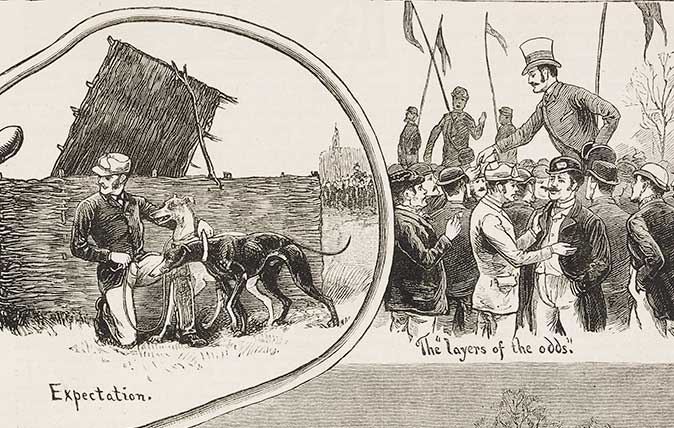

The amazing tale of the Waterloo Cup, the other event created by the man who invented the Grand National

The Grand National is woven into our collective identity, but few people today know of the other event created by

The millionaire who created a real-life toy train set on a human scale

The astonishing assemblage of buildings, machinery and memorabilia at Fawley Hill, Buckinghamshire — the home of Lady McAlpine and the late

11 breathtaking photographs from the 2018 Landscape Photographer of the Year competition

We've picked out eleven of our favourite landscapes from the 2018 Landscape Photographer of the Year award.

Richard E. Grant: 'Not a day goes by without somone quoting Withnail & I at me'

Emma Hughes talks to the actor about Withnail & I, singing for his supper – and sniffing trees.

-

Designer's Room: A solid oak French kitchen that's been cleverly engineered to last

Designer's Room: A solid oak French kitchen that's been cleverly engineered to lastKitchen and joinery specialist Artichoke had several clever tricks to deal with the fact that natural wood expands and contracts.

By Amelia Thorpe

-

Chocolate eggs, bunnies and the Resurrection: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 18, 2025

Chocolate eggs, bunnies and the Resurrection: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 18, 2025Friday's quiz is an Easter special.

By James Fisher