The world's greatest wildflowers: Where to find them and why they bring us so much joy

Lady’s slippers by the hundreds if not thousands, hillsides golden with daisies, swards of salvias: Sarah Raven salutes Bob Gibbons, who has dedicated the best part of his life to finding and documenting wildflowers. Photographs by Bob Gibbons.

We have an interesting relationship with ‘wild’ flowers. Filming a mini BBC series on pollinators 10 years ago, I watched what people did when walking through city meadows in full flower. Wild annuals had been sown in a series of semi-dilapidated, inner-city spaces in Sheffield, Birmingham and Leeds. Everyone loved the abundance, but, more than that, the vandalism, graffiti and drug-taking had, at least from those places, totally disappeared.

Some very occasionally picked a small posy to take home (which was encouraged), but no one, in any of the sites, had trashed the flowers. No one biked through them or stamped them down. People dropped far less litter – the meadows were left pretty pristine.

Flowery abundance brings out the best in us and we have a similar reaction to meadows in the wild. We seem to feel younger, more joyful, even elated, when we come across a proliferation of wildflowers. People who have hardly noticed flowers in their whole life are overcome and travel miles to get another ‘fix’. It becomes addictive because it makes us feel so good.

I became an addict as a child when I was taken, at the age of seven, by my botanist father to see the thrift and sea lavender on the Norfolk coast, a couple of hours from where we lived. We followed up with snakes-head fritillaries in the Thames valley at Cricklade and then the mass of miniature pansies and marigolds on the machair in the Outer Hebrides.

Later, he took me to see the richness of geraniums, gentians and orchids in the limestone pavements of the Burren in western Ireland and, further afield, we found swathes of crocuses and aconites on the snowline in the Italian Dolomites and roadside cliffs full of the widow iris, Hermodactylus tuberosa, in Corfu.

I now know that wildflower abundances make me feel deeply relaxed and, at the same time, exhilarated and I gather that, for many people, it’s exactly the same.

That’s why Bob Gibbons’s book on Wildflower Wonders is what we all need. Bob has travelled the world to photograph the best accessible wildflower sites you’ll find on the planet. He started nearly 50 years ago on an overland plant-collecting trip to Afghanistan and has continued ever since to seek out and record the most outstanding places to see natural displays.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Bob loves landscape and he loves plants, and the combination of the two is what’s so remarkable about each of his top 50 selections and how he records them. The places he shows us are not so much for the hand-lens-brandishing botanist, but for the plant lover who wants to have a good time.

In Estonia, it’s where the sites of lady’s slipper orchids are not in a secretly protected group of one or two, but where they grow by the hundreds, if not the thousands, within a few square miles. It’s where, in Washington State in America, you’ll find blue lupins, penstemons and the vivid-orange cliff Indian paintbrush buzzing with pollinator hummingbirds, all stretching as far as you can see and where, in southern Transylvania in Romania, brown bears – from time to time – stride through the woods that enclose the meadows packed with milkworts, salvias and butterfly orchids.

Bob runs tours to many of the best places, but his work is more than that: he’s also an excellent photographer. What you want from wildflower photographs is not the beautiful specimen in isolation, as if it had been shot in a garden, but the sense of the drama of the place in which it grows. You want the plant to stand like a diva, commanding the centre of its natural stage, and that’s what Bob captures so well.

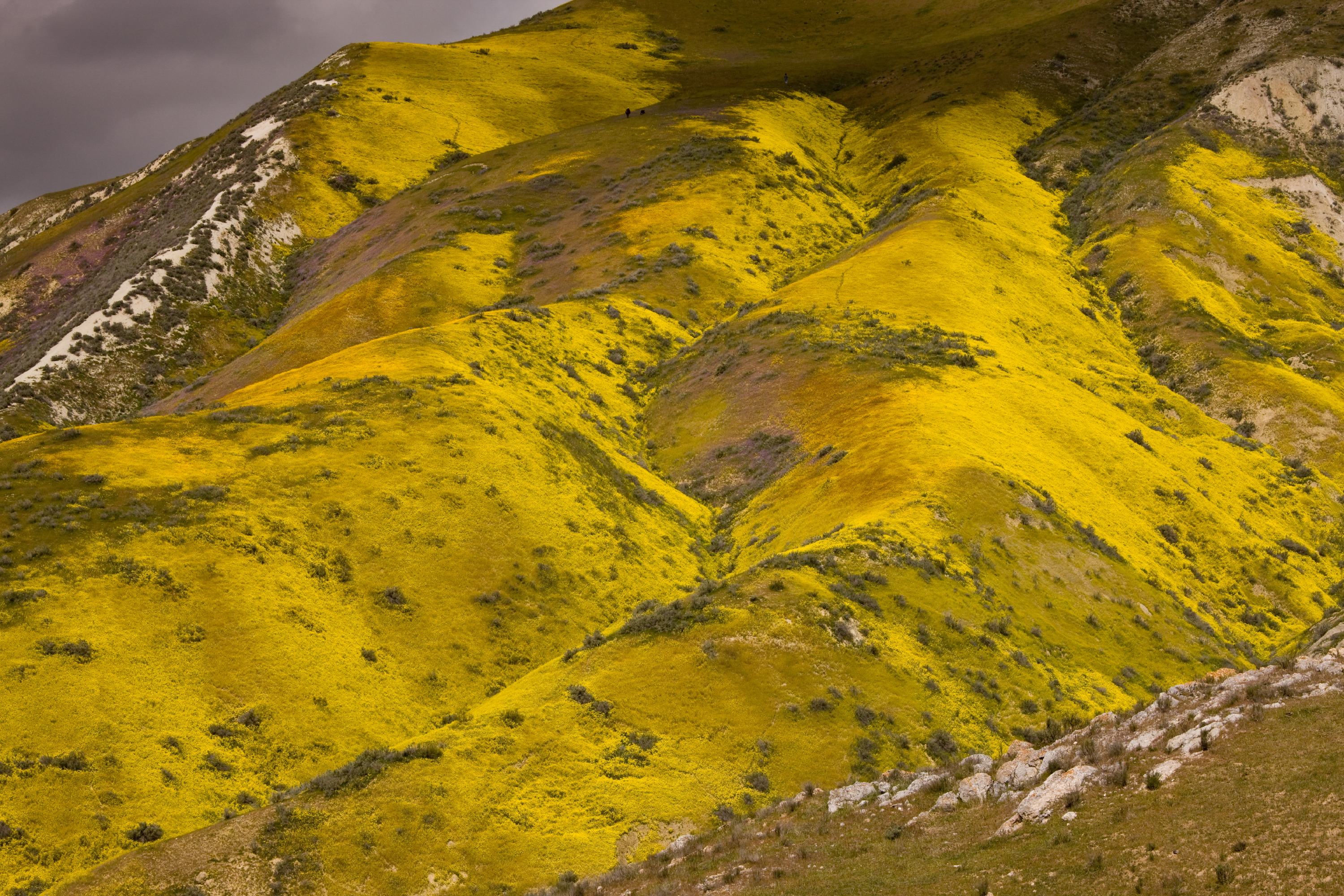

He explains the occurrence of these colour explosions, too. I visited the crazily bright wildflower carpets near Darling in the South African Western Cape this September and was stunned by the completely over-the-top colours of the different wild plants growing cheek by jowl.

Why have these plants evolved to be quite so showy, with colours more fit for a 1970s disco than a field? As Bob says, it’s because they have a scarily short window to set seed and they don’t necessarily get a chance to do this every year.

If there’s been a drought and not enough rain through the winter, many of the flowers remain dormant the following spring and perhaps even the next, so, when the right moment comes, they have to really go for it to get those few pollinators to come and do their stuff.

Apart from the obvious factor of having not been destroyed by Man, this is what creates the best sites – where you get a few intensely flowery weeks between cool winter and hot, dry summer or, in mountainous areas, between snow-melt and the first frosts.

That’s the character that allows these places to be such reliable flowery paradises.

The brighter and/or the more scented the bloom, the greater the chance of being fertilised. That’s why wild freesias grow 2in from apricot Moraea, iris-like Babianas next to scarlet-velvet saucers of Romuleas and night-opening Hesperanthas, all merging into an ecstatic sward.

I remember being told that walking through the wildflower meadows of Bhutan, made you feel as if you were at your own wedding, but where the confetti wasn’t paper, but butterflies in clouds. That’s the thing about these places – the flowers make them insect- and bird-rich, too. Wherever you look is zinging and pinging with biodiversity. That’s why it feels so life-enhancing.

Bob doesn’t deny the threats to some of these places, however. He offers good advice about the areas that are well protected and those less well so.

A visit to at least one has to be near the top of everyone’s do-before-you-die list and, throughout this winter, even merely looking at the pictures in Wildflower Wonders will help improve your mood.

Where to see ferns: Six of the most spectacular places in Britain

Country Life's gardens editor Tiffany Daneff picks out some of the finest ferneries in Britain.

What to plant if you're thinking of putting a willow in your garden

Charles Quest-Ritson offers advice on this incredibly vibrant plant.

Credit: Plas yn Rhiw - National Trust

Plas yn Rhiw: An intoxicating Welsh garden that time forgot

Non Morris visited one of the most beautiful gardens in Wales, and came away utterly smitten.

Alan Titchmarsh: How to keep a perfect pond

Alan Titchmarsh says that now is the time to clear out the weeds and keep your pond in top condition

Credit: Alamy

Country Life’s best gardening tips of 2018: Wisteria, Christmas trees and getting rid of box moth caterpillars

Our panel of experts includes writer and broadcaster Alan Titchmarsh and Charles Quest-Ritson, author of the RHS Encyclopedia of Roses