Where to see a murmuration of starlings in Britain — but you'd better bring ear defenders

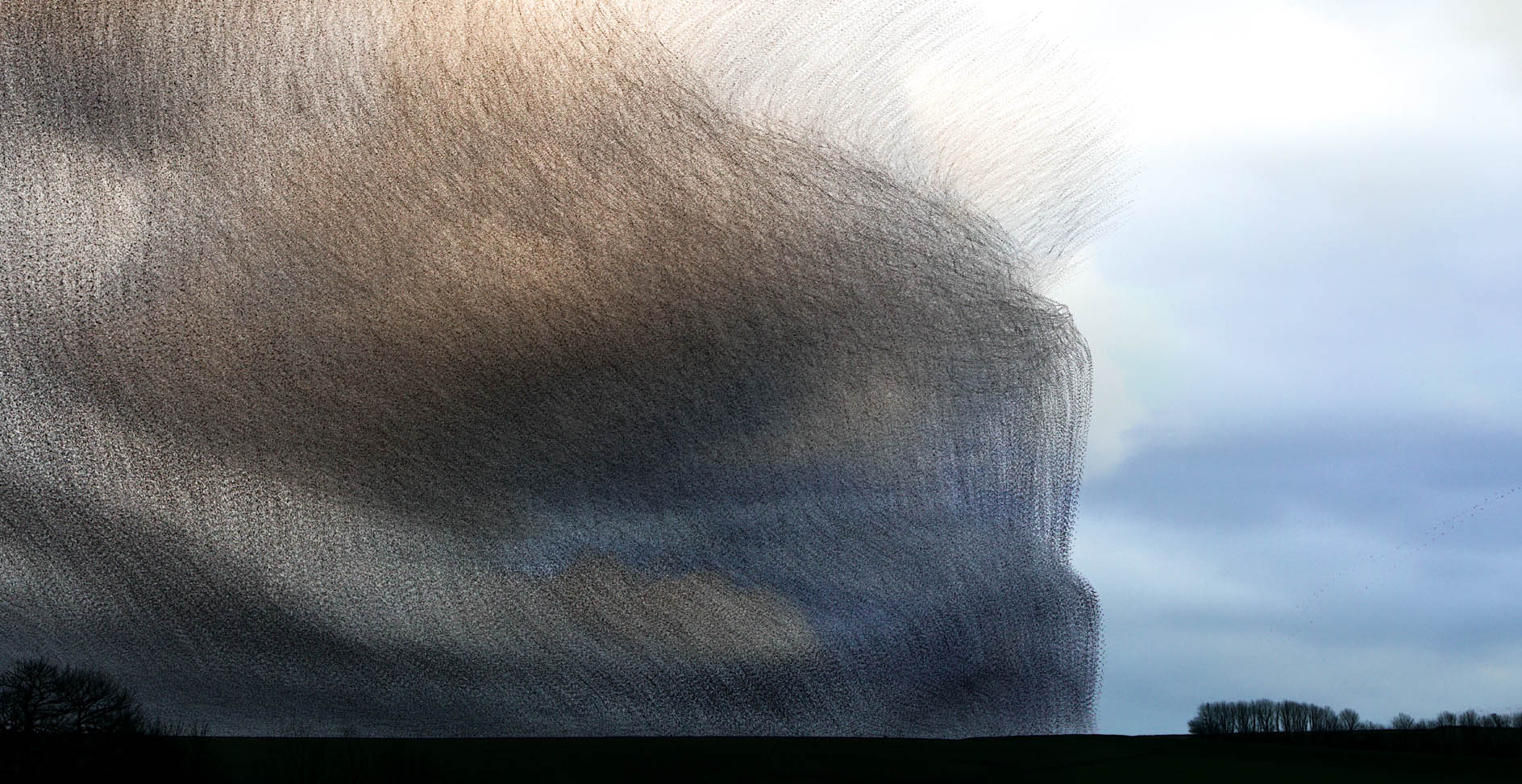

Rolling like an enormous shape-shifting black cloud, as countless birds swoop and dive in unison, the starling murmuration is a spellbinding phenomenon. Simon Lester is mesmerised — and shocked at the noise.

At a distance, a starling looks black and boring — it’s often strutting around and is the bully of the bird table. Close up, its glossy emerald-green and deep-purple plumage has a beguiling beauty of its own, with an iridescent sheen to rival any of the dandies of the bird world.

However, it is not its plumage that has brought the starling fame and public attention: it is the pre-roost extravaganza of avian antics, the collective aerial dance known as a murmuration of starlings.

Where to see a murmuration of starlings in Britain

- Shapwick Heath, part of Avalon Marshes, near Glastonbury, Somerset

- Aberystwyth Pier, Ceredigion

- Brighton Palace Pier, East Sussex

- RSPB Leighton Moss Nature Reserve, near Carnforth, Lancashire

- RSPB Fen Drayton Lakes Nature Reserve, near Cambridge, Cambridgeshire

- RSPB Minsmere Nature Reserve, near Saxmundham, Suffolk

- RSPB Ham Wall Nature Reserve, Ascott, Somerset

- Gretna Green, Dumfries & Galloway

- Albert Bridge, Belfast

- RSPB Newport Wetlands Nature Reserve, Newport, South Wales

- Whisby Nature Park, Thorpe on the Hill, Lincolnshire

- Attenborough Nature Reserve, near Nottingham, Nottinghamshire

"It’s like looking through a colossal, monochrome kaleidoscope"

From October onwards, our resident population of starlings is boosted by birds migrating from colder European climates. British farmland generally remains unfrozen, giving the vast numbers that overwinter in this country a ready food supply.

Many thousands of birds drift into a chosen roost site — it may be a quiet reedbed, a wood, open farmland or, more bizarrely, a city park or pier — from a radius of about 13 miles. As the sun begins to set, there’s a gradual build-up of birds, which sit around chattering and whistling as only starlings do before starting to come together, black dots drawn in from afar to join the ever-growing swirling mass.

Patterns start to form, yet change again in the blink of an eye. It’s like looking through a colossal, monochrome kaleidoscope that sculpts the most breathtaking organic shapes, but, instead of inert pieces of glass making the patterns, it’s thousands of pumping hearts beating as one. As the birds wheel and turn, they block out the light, giving the illusion of a solid ball—it’s no wonder that the Danes describe these murmurations as the sort sol, meaning black sun. The entire spectacle is mesmerising—lasting about half an hour before some birds start to settle into their chosen roost—with great ribbons descending en masse, as the sky darkens into night and the stragglers drop in to give the final curtain call of the night’s performance.

"The sound is akin to the roar of a jet plane overhead"

If you see a murmuration from a way off, however, you may not appreciate the volume of the noise this aerial display generates. I have stood directly under a starling roost—trying to deter them from settling in a small wood—and can attest that the sound is akin to the roar of a jet plane overhead, as thousands of beating wings rip through the air and, when they change direction, you can feel the air move.

Why do starlings perform this aerial ballet, one of the finest examples of synchronised flying? One theory is that flying as one body and then huddling together in their roosts helps to protect them from the cold. Nonetheless, the main reason that starlings form a murmuration is to deter predators. When going about their business as individuals or in small groups, they are vulnerable to raptors — mainly sparrowhawks, hen and marsh harriers — who will take advantage of any readily available food supply. If these predators are present, then the starlings usually gather on a greater scale and the performance lasts longer.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Being part of this ever-changing, wheeling and pulsing mass makes it almost impossible for an assailant to pick out an individual bird. It is thought that birds move around within the flock, taking it in turns to be on the outside where they’re more vulnerable to attack.

How starlings in a murmuration follow the seven birds around them

[Read full article: How do starlings murmurate?]

The act of confounding predators is more effective if the flock moves as one in perfect coordination. But, in reality, an individual bird cannot know what is happening throughout the whole massive congregation. Scientists believe that each bird is aware of and responsive to the seven birds closest to it. Being able to align their actions to those of their close companions avoids catastrophic crashes.

Why only seven neighbours? Well, any more than that and it becomes harder to keep track of flight patterns, which dramatically reduces birds’ response time. The act of constantly shifting, as one formation, requires each starling to be on full alert, in a state of ‘criticality’ — a constant tipping point at which a system is on the edge of making a transition from one state to another. Every bird is constantly on the lookout, poised on the edge of making a sudden change of direction. If one makes a sudden change to its flight path, the whole flock transitions, meaning each bird influences all the others in terms of direction and speed.

Therefore, it seems that we must thank the starling’s effective and most theatrical way of foiling predators for one of Nature’s greatest shows. Much as we like to observe these awe-inspiring aerial acrobatics, however, it is not always good news if hundreds of thousands of starlings decide that your plantation, town park or square is a good place to bed down for the winter. That number of bottoms can produce a damaging amount of acidic droppings, which will kill plants and trees and can damage stone, brick and paintwork on buildings and cars. In urban situations, the noise and smell can also be a source of annoyance to residents. Starlings can also become problematic around dairies and farm buildings, by fouling feedstuff and potentially spreading disease.

Far better, then, to observe these magnificent flying machines from afar this autumn.

Eight surprising facts about Starlings

- Sturnus vulgaris stands at 8½in tall and juveniles (above) are brown and spotty

- Numbers have declined by 81% since 1970, likely due to a loss of permanent pasture, increased use of farm chemicals and a shortage of food and nesting sites

- Gregarious birds, they live and feed—on grassland invertebrates, cereals and fruit—in small flocks throughout the year

- After laying four to seven bright-blue eggs in April—in scruffy nests, located in crevices and holes in buildings or trees—they sometimes produce a second clutch

- Many woodlands and copses throughout the country are known as ‘Starling Wood’, thanks to the birds’ propensity for converging on arboreal roosting sites

- Their glistening feathers have long been sought by milliners and fishermen, as they are ideal for fashioning soft-hackle flies

- Starlings are great mimics, not only of other birds, but also manmade sounds, such as car alarms and mobile-phone ringtones

- A delicacy in some European countries, their meat has a strong gamey flavour

How do starlings form murmurations?

Murmurations of starlings — the vast clouds of thousands of birds, flocking and swooping through the sky — are one of nature's

Collective nouns for birds

We celebrate our favourite collective nouns for birds, from the weird and the wonderful to the most curious.

Jason Goodwin: 'The flock widened and contracted, filling the whole sky with motion: expansive, pure theatre'

Our spectator columnist comments on the end of summer, as murmurations of wheeling and diving birds herald the beginning of

-

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attached

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attachedUpper House in Derbyshire shows why the Kinder landscape was worth fighting for.

By James Fisher

-

The Great Gatsby, pugs and the Mitford sisters: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 16, 2025

The Great Gatsby, pugs and the Mitford sisters: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 16, 2025Wednesday's quiz tests your knowledge on literature, National Parks and weird body parts.

By Rosie Paterson