The slithering truth about the snakes of Britain, from grass snakes to the 6ft beasts that roam central London (yes, really)

Forever associated with sin, these elongated reptiles are much misunderstood contributors to our ecosystem, believes Annemarie Munro.

The thought of snakes rarely produces warm, fuzzy feelings; in fact, most people shudder or flinch. Let’s face it — these elongated reptiles have a negative reputation, exacerbated by folklore, literature and religion. In the Bible, the smooth-talking serpent was the cause of the downfall of Mankind as Eve succumbed to temptation, committing the first sin. In Greek mythology, Medusa had snakes for hair and eyes that turned people to stone, a trait shared with the basilisk of the ‘Harry Potter’ series, which brings the link between snakes and evil into present-day storytelling: the personification of evil who appears more snake-like than human, Voldemort unleashes ‘pet’ python Nagini on his victims at Hogwarts.

In our increasingly fragile ecosystem, why, then, should we be willing to share resources with our slithery friends? They may not be cuddly or cute, with dry scales, tiny heads and forked tongues, but the snakes of the UK are worth a second look. Despite being paired with evil throughout history, they have also represented good and are twinned with healing, fertility and rebirth.

The Celts thought of serpents as symbols of feminine power and fertility, due to their habitat being among weeds and roots deep in the earth — the life-giving womb. Ancient Egyptians saw this powerful animal as a symbol of protection and a snake is often depicted as sheltering Buddha from storms as he meditates.

As we all know, snakes possess the ability to shed their skin — the average snake sheds two to four times a year. It takes about a week to slowly shrug off the old garb through a process called ecdysis and they do so to allow them to grow — a snake’s scaly skin is designed to protect it from moisture loss and provide a tough outer layer, but it cannot grow. This habit is why snakes have been linked in several cultures to rebirth or transformation; as they slough off their old skins, they take on a new life.

Some of us like to lie in the sun and feel the heat revive us, but snakes really need to sunbathe — they absorb heat to convert to energy, which winds them up long enough to mate or kill prey. If they get too hot, they dive into undergrowth or a pond to cool down again. In cold weather, they lack the heat and, therefore, the energy to move. As a result, they hide before becoming sleepy and, finally, stop moving altogether, falling into a state of torpor until the weather gets warmer. Snakes are living thermometers. They are known as cold-blooded or ‘poikilothermic’ animals, but their relationship with the climate is intimate — it literally controls their ability to function.

The species found in the UK are grass snakes (Natrix helvetica), adders (Vipera berus) and smooth snakes (Coronella austriaca).

There is also a wildcard among them: the Aesculapian snake (Zamenis longissimus), a non- native immigrant that is non-venomous, feeds on rodents and can be found in North Wales and in the Camden region of London. (A friend of the son of our editor, Mark Hedges, came across a 6ft specimen in Regent’s Park just the other week, in fact. He called London Zoo to let them know one of their reptiles was missing, only to be told not to worry, and that the snake he'd seen was merely a harmless Aesculapian with just as much right as any of us to use the park.)

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Reptiles are a significant component of food webs, filling a critical role both as predator and prey to maintain the balance of species. The smooth snake is a constrictor, crushing to death in its coils prey such as sand lizards, slow worms, insects and baby birds. In turn, it is hunted by foxes, pheasants, badgers and weasels, which all enjoy a smooth snake as a tasty snack.

Rarely seen, Coronella austriaca can only thrive in a heathland habitat, where sandy soil gets warm in the summer sun and low-growing heather, gorse and grasses provide camouflage and cover. It is a mottled brown colour with indistinct patterns along its body and was recently reintroduced to heathlands in West Sussex and Devon. Before this, it could only be found in Hampshire, Dorset and Surrey.

The grass snake is a slithering, green-grey coil of stealth, with a distinctive yellow, cream or white band around its neck like a vicar’s collar. Its eyes have small, round pupils, which make it appear a little more friendly than the blank, crescent-moon glare of the adder. Found throughout the British Isles, grass snakes are particularly good swimmers and will be attracted to ponds and lakes, where they can hunt for the ideal meal of a fat toad or a frog. In gardens, log piles make a perfect home and compost heaps provide warmth; Natrix helvetica will create holes inside them and coil up for the winter months.

The adder is the UK’s only venomous snake. Living in a woodland ecosystem and keen to lie in the sun to gain heat, it’s constantly ready to slip away into the undergrowth if disturbed. It hunts for small amphibians, mice and other woodland creatures, swallowing prey whole. The colour of fallen autumn leaves, these stocky snakes are about 3ft long, with a black zig-zag along the body.

Despite Vipera berus’s valiant attempts to stay out of the way, both people and dogs do get bitten — an act of self-defence resulting in 50–100 adder bites each year, according to research by Amphibian and Reptile Conservation. Medical treatment is available and most people (70%) suffer few symptoms. However, very rarely, a bite can cause severe side effects; occasionally, even death.

On the flip side, adders also save lives by contributing to science — their venom has been researched and examined closely. It causes the rapid death of prey by delivering a local toxin into the blood, which starts to break down the blood, cells and tissue, helping the snake to digest its food once swallowed. Medical researchers have emulated this chemical reaction to create medicines for humans, with one example being a drug that helps reduce blood pressure. Other research of snake venom is helping to explore cures to cancers and neurological disorders.

It becomes ever more important, therefore, to take a fresh look at the reptiles that skulk around our neighbourhood. The initial instinct may be to avoid and eradicate them — St Patrick was lauded for driving all snakes out of Ireland — but snakes are needed to maintain the productivity of our ecosystem, to contribute to further medical advances and, if nothing else, to treat us to the swish of a tail disappearing into long grass.

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

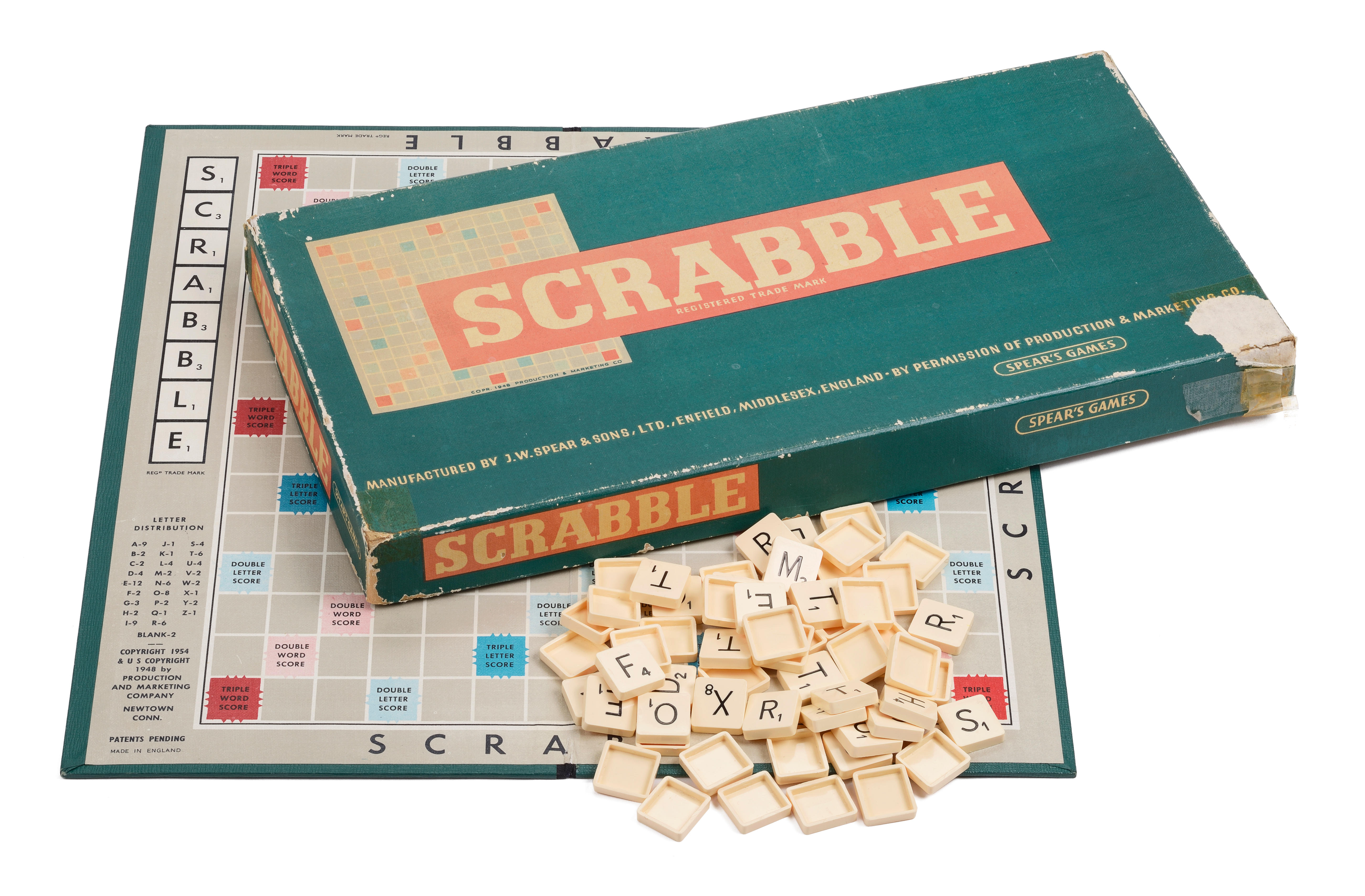

How to win at board games, from Monopoly and Cluedo to Scrabble and Snakes and Ladders

As millions of people around the country are set to have an enforced period at home, it'll be time to

Credit: Marcus Peel / Artichoke

A Tuscan kitchen reborn: 'When we first took it on a tree was growing through the kitchen and the basement was full of snakes'

The secret life of toads, from frenzied procreation to hunting snakes in the night

Despite their semi-webbed feet, warty skin and bulging eyes, toads are more endearing than Shakespeare’s witches would have us believe,

Country Life Today: What’ssss down there? Six-foot python found in a carpark

In today's round up, we stumble upon a snaky discovery, reveal English Heritage's new plans for York's Clifford's Tower and

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Ford Focus ST: So long, and thanks for all the fun

Ford Focus ST: So long, and thanks for all the funFrom November, the Ford Focus will be no more. We say goodbye to the ultimate boy racer.

By Matthew MacConnell

-

‘If Portmeirion began life as an oddity, it has evolved into something of a phenomenon’: Celebrating a century of Britain’s most eccentric village

‘If Portmeirion began life as an oddity, it has evolved into something of a phenomenon’: Celebrating a century of Britain’s most eccentric villageA romantic experiment surrounded by the natural majesty of North Wales, Portmeirion began life as an oddity, but has evolved into an architectural phenomenon kept alive by dedication.

By Ben Lerwill