The man who spent a year spotting all 59 of Britain's native butterflies

Once oblivious to butterflies, Robin Page became so entranced by their delicate beauty that he embarked on a year-long safari to spot every native British butterfly — as well as some foreign visitors.

When did I become obsessed with butterflies? The answer is simple — I don’t know.

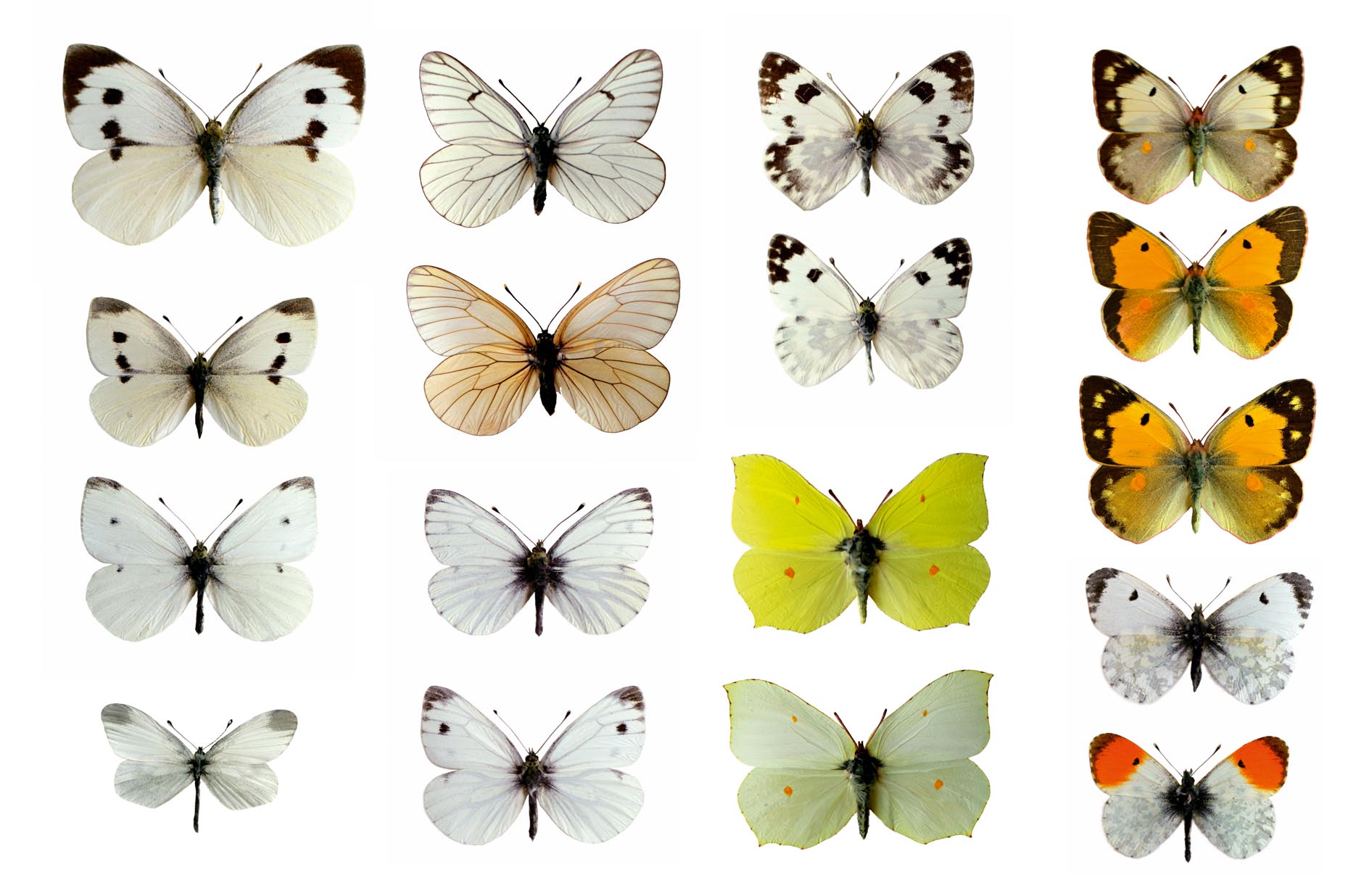

As a child, I quickly became aware of them. There were white ones, ‘cabbage whites’, that father blamed for eating our cabbages as caterpillars; brightly coloured ones in the spring that fluttered against the window panes, trying to get out of the house; and others in the autumn that tried to get in. However, at that stage, that is as far as me and butterflies went.

Then, years later, I met an amazing countryman — well, a Londoner who had moved into the countryside as a child during the Second World War as an evacuee — called Gordon Beningfield.

By the time our paths crossed, he had metamorphosed from an urban child at risk from war into a quite extraordinary watercolour artist and conservationist; what a transformation. He was also a man who suffered with dyslexia, yet could hold an audience enthralled with words — as long as they were spoken, as opposed to written words, because ‘spellin’ was beyond ’im’.

With a paintbrush in his hand, he turned butterfly illustration into art, butterflies into conservation allies and his artwork into a countryside crusade.

His pictures told the story of changing Britain, warning against the double meaning of the word ‘progress’: a boggy place drained, wildflowers sprayed, an orchard uprooted and a new town — a planner’s dream, a politician’s boast, an environmental insult, a butterfly disaster and a countryside nightmare.

My life changed still further one April day when I was standing in a bog with Gordon, close to his home in Hertfordshire. The cuckoo was calling and the cuckoo flower was flowering. ‘There’s an orange tip,’ he said, pointing to a beautiful butterfly with orange tips to its wings. ‘Look here,’ he continued, ‘they lay their eggs on cuckoo flowers.’

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Within a minute, he had found an egg and butterflies had become more than wings — they became wings, flowers, plants and seasons. The wings changed, too. I did not simply see the odd whites and yellows and peacock eyes. I saw blues and browns, large and small, fast wings, slow wings and wings that opened to absorb the sun.

They all linked sun, air, water, flowers and people — and yes, they were ‘indicator species’, indicating health or hindrance in the countryside and the atmosphere.

“How can butterflies, with their beautiful, fragile wings, fly through the sharpest and deadliest thorns in natural Britain, navigating with ease and certainty?”

Astonishingly, although Gordon was dyslexic, he became an expert on the books of Thomas Hardy (how did that happen? I have no idea), introducing me to Dorset and the world of Hardy, as well as butterflies. He died in 1998 and I still miss him.

Yet, he was something else, too — he made the seasonal flutter of butterflies and their beauty fun. Fun is so important in conservation and it’s such a pity that so many modern conservationists fill us with gloom and doom, replacing smiles with scowls and twisted vowels. Gordon was a serious conservationist, but he was also a man of smiles and laughter.

In turn, butterflies have become dazzling creatures of smiles and laughter for Mrs Page (Lulu) and me. So much so that, every year, which one of us sees what, when, where and ‘first’ becomes important — even competitive. In addition, our love of butterflies has followed us to Africa.

When some are searching for lions and cheetahs, I will often be looking at the colour, light and movement of butterflies — fragile and delicate in a hard, hostile world. When at waterholes ‘on safari’, I have spotted silken wings, whereas others have seen nothing but monkeys having a scratch.

This got me thinking, what about undertaking a butterfly safari here in Britain? A trip around the UK in the hope of seeing all British butterfly species in a single year, raising money for conservation at the same time. The first problem was establishing how many varieties we have in Britain — even the experts don’t agree. I decided to aim for 58 or 59, with a couple of vagrants (such as the monarch that sometimes gets blown in from America in the autumn and the Camberwell beauty, an occasional visitor from Europe that was first seen in 1748) thrown in for good measure.

In 2002, I embarked on my butterfly safari. In theory, it took the entire year, covering more than 11,000 miles and raising £10,000; but, in reality, it’s continuing now and I still search for the monarch and the Camberwell beauty every year. The venture exhausted me.

Butterflies are so frustrating, weather driven, sun inspired, unpredictable and first described by an astonishing assortment of British eccentrics. For example, one of the earliest spring fliers is the holly blue — a butterfly of deep, striking blue, that lays its eggs on holly as a food plant for its caterpillars, switching to ivy for its second brood, so shouldn’t it be called ‘the holly and the ivy blue’?

“You might wonder which was the most attractive. It would be simple, and partially true, to say the swallowtails on the Norfolk Broads. My number one, however, would be the small and astoundingly beautiful small copper”

What about the black hairstreak and the brown hairstreak? The caterpillars of both feed on the buds and leaves of the blackthorn, a tree or shrub that’s now scarce because of scrub clearance. How can butterflies, with their beautiful, fragile wings, fly through the sharpest and deadliest thorns in natural Britain, navigating with ease and certainty? Two of our most astounding butterflies — the red admiral and the painted lady — are migrants.

Indeed, Lulu and I have been fortunate to witness hundreds of painted ladies, which hail from the Meditterranean, hitting land over a rough sea on the Isles of Scilly, in a sight that was astonishing, fluttering and staggering. There were plenty of oddities, too. Why did the graylings among the Norfolk sand dunes insist on landing on my feet, where my overheating sports shoes seemed to hold much appeal?

Out of the 59 species seen and verified thanks to a variety of helpful companions, you might wonder which was the most attractive. It would be simple, and partially true, to say the swallowtails on the Norfolk Broads. My number one, however, would be the small and astoundingly beautiful small copper, closely followed by one of Gordon’s favourites, the marbled white — a lover of hay meadows, sunlight and waving grass — which usually flies from mid June until the end of July.

On my small farm in Cambridgeshire, the marbled whites arrived in a cardboard box, courtesy of Trevor, a BT van driver. He had noted that scrub was invading land owned by British Rail — or whatever it happened to be called at the time — which was threatening an established colony of marbled whites. Consequently, like the good conservationist he is, Trevor collected the butterflies and chrysalises and released them in my grass fields. From there, they have spread over the whole farm and parish — Trevor, what a conservation star you are.

This leads me to another butterfly buff who must be mentioned, the late Christopher Booker. Forget his excellent political journalism — and his loathing for ‘group think’ — his great love and passion was butterflies. Lulu and I once enjoyed an unforgettable day with him, watching the introduced large blues at the National Trust’s Collard Hill in Somerset.

Some enthusiasts have put butterflies on an ornithological scale of importance and beauty. Hence, for me, the small copper equals the skylark, the meadow brown the wood pigeon and the large blue the osprey. These comparisons are nonsense, really, but they’re fun and I think Gordon would have approved.

Which species, however, could match the incredible purple emperor? Strangely enough, when I was lucky enough to see seven magnificent purple emperors in the air at once — close to the home of that late butterfly legend Dame Miriam Rothschild — two of them were, once again, attracted by the state of my feet. In my lexicon of favoured butterflies and birds, the purple emperor must equal the cuckoo, which I’m pleased to say I have heard several times this year.

When the 2002 safari was done and dusted, I wrote a book called The Great British Butterfly Safari. Extremely politically incorrect, it was described by the late Prof David Newland, another butterfly obsessive, as ‘an enjoyable read — sure to raise a smile’.

Finally, I have a confession. Three years ago, I saw pristine monarch butterflies flying — not in England, sadly, but on St Helena in the South Atlantic Ocean. The only problem was that I left my Tilley hat on a bench there, so, if any reader is lucky enough to go and finds my hat, please let me know. Also, do have a St Helena coffee, made from ancient Arabian coffee beans — it’s sensational.

Spotting all 59 of Britain's native butterflies: How Robin ticked off his butterfly calendar

- January 7 Small tortoiseshell at Bird’s Farm, my small Cambridgeshire farm

- March 16 Brimstone, farmhouse garden

- March 27 Peacock, farmyard

- March 30 Speckled wood, farmhouse garden

- April 3 Large white and comma, Bird’s Farm vegetable garden

- April 17 Small white, Bird’s Farm vegetable garden

- April 23 Orange tip, grass meadow at Bird’s Farm

- April 25 Small copper, in the Bullock’s End meadow, and a holly blue, flitting around hedgerow ivy, followed by a common blue in a grass meadow at Bird’s Farm

- May 9 Green-veined white, green hairstreak, pearl-bordered fritillary, grizzled skipper, wall, dingy skipper and red admiral in a wide valley near Welshpool, in Powys, Wales

- May 17 Duke of Burgundy fritillary on the edge of Whipsnade Zoo, near Dunstable in Bedfordshire

- May 24 Chequered skipper near Fort William in the Scottish Highlands

- May 31 Swallowtail, Hickling Broad, Norfolk

- June 1 Wood white at Salcey Forest, Northamptonshire

- June 2 Brown argus in Telegraph Field, Lark Rise Farm, next to Bird’s Farm

- June 5 Glanville fritillary, small blue and adonis blue, Isle of Wight

- June 9 Small skipper, Bird’s Farm

- June 14 Meadow brown at brook meadows and a small heath at Bullocks End meadow at Bird’s Farm

- June 17 Painted lady and marsh fritillary at Cerne Abbas, Dorset

- June 20 Marbled white, small pearl-bordered fritillary and Essex skipper at Dolebury Warren, Mendip Hills

- June 21 Black hairstreak and large skipper, near Oundle, Northamptonshire

- June 24 Heath fritillary and ringlet, Thrift Wood, Essex

- June 26 Large blue, Collard Hill, Somerset

- July 4 Grayling and silver-studded blue, Minsmere, Suffolk

- July 7 Silver-washed fritillary in a Herefordshire wood

- July 8 Large tortoiseshell, flying out of a cardboard box in Cambridgeshire

- July 12 Dark-green fritillary and high-brown fritillary, near Welshpool in Wales, where old-fashioned farming methods and cutting of bracken for animal bedding exposes violets (food plant of high-brown caterpillars) and account for some 25% of the Welsh high- brown population being there

- July 13 Gatekeeper, farmhouse garden

- July 14 White-letter hairstreak in a small remnant of elm — its food plant — near my home

- July 14 White admiral at Bramp ton Wood, Huntingdonshire

- July 16 Mountain ringlet (also called the small mountain ringlet) Lake District, Cumbria. A survivor from the Ice Age going back 10,000 years and a true Alpine butterfly, together with the Scotch argus, we found it at last, almost at the top of Cold Pike, at an altitude of about 2,150ft. Followed, in the afternoon, by a large heath at Meathrop Moss. We then went on to an old limestone quarry managed by the Cumbria Wildlife Trust for a northern brown argus

- July 22 Purple hairstreak, Brampton Wood, Huntingdonshire

- July 25 Purple emperor, Fermyn Woods, Northamptonshire

- July 31 Chalkhill blue at Devil’s Dyke on the Cambridgeshire and Suffolk border

- August 2 Clouded yellow and Lulworth skipper, Lulworth Cove, Dorset

- August 13 Silver-spotted skipper and brown hairstreak, Porton Down, Wiltshire

- August 14 Scotch argus, Arnside Knott, Cumbria

Total 59 butterflies

The author’s book, ‘The Great British Butterfly Safari’, is available to buy for £25 — including postage and packaging, together with a complimentary butterfly wall chart — by sending a cheque made payable to Robin Page at Bird’s Farm, 2, Haslingfield Road, Barton, Cambridgeshire, CB23 7AG

How to re-wild your garden, from ponds and trees to attracting butterflies and hedgehogs

Joel Aston — one half of the 'butterfly brothers', along with his sibling Jim — explains how rewilding gardens to attract

12 of Britain's most beautiful butterflies – and the truth about their chances of survival

Beautiful, delicate and harmful to no-one, our iconic butterflies are facing an increasingly perilous existence – that's the conclusion reached

Credit: Paul Fawley / Khamama

The beautiful works of art made from butterflies' wings — but only after they've died from natural causes

Spectacular butterfly specimens from across the world are being given a luxurious afterlife as jewellery boxes, humidors and watches. Nick

-

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbinding

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbindingAn exhibition on the legendary bookbinder Roger Powell reveals not only his great skill, but serves to reconnect us with the joy, power and importance of real craftsmanship.

By Hussein Kesvani

-

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary Britain

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary BritainCourtesy of our ‘special relationship’ with the US, Spam was a culinary phenomenon, says Mary Greene. So much so that in 1944, London’s Simpson’s, renowned for its roast beef, was offering creamed Spam casserole instead.

By Country Life