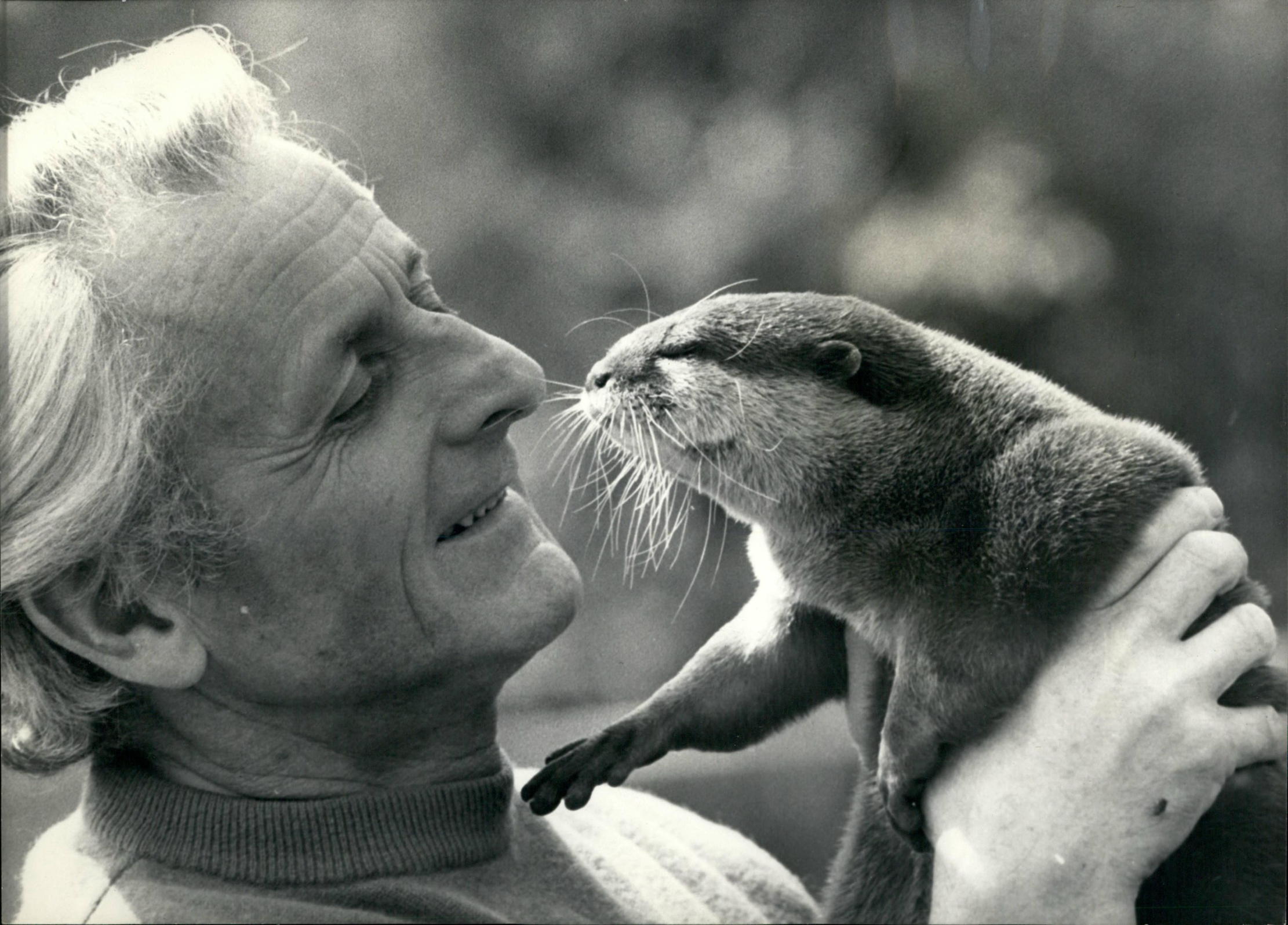

The Legacy: Philip Wayre, the man who saved the otter

The heartwarming tale of how this film-maker and naturalist restored the otter to English rivers.

So much gloom is written about conservation statistics that we tend to forget the success stories. The heartwarming tale of how Philip Wayre, a film-maker and naturalist, restored the otter to English rivers is one such example. By the late 1970s, the only healthy British otter populations were in Scotland and odd spots in the South-West, due to the pollution of English rivers by pesticides; sightings of this enchanting mammal were painfully rare.

Wayre (1921–2014) and his wife, Jeanne, had started the Otter Trust in 1971 to highlight the problem; their aim was to breed the animals in captivity to release into the wild. They released the first captive-bred otters into the River Blackwater in Suffolk in 1983.

Wayre had already made an unsuccessful foray into agriculture when he turned his Norfolk farm into a wildlife park, chiefly to cater for the animals he had brought into television studios and then couldn’t bear to get rid of. By 1996, 130 otters had been released across 11 counties and, by 2008, it was a case of job done: the animals could be found in every English county and the Otter Trust was closed.

'He also trained birds of prey and was an expert on the ornamental pheasant'

As Country Life reported at the time, Wayre, by then in his eighties, said: ‘We had achieved what we set out to do. There was no further reason for us to keep captive otters.’ Pollution — and traffic — remain dangers, but Lutra lutra is now classified as ‘least concern’ on the Red List in England.

Wayre's Norfolk Wildlife Park was the first of its kind in Britain. It was here that he was able to breed, for the first time in captivity, the European wolf, as well as the brown hare. Not content with just land- and water-faring animals, he also trained birds of prey and was an expert on the ornamental pheasant, keeping several species, including the silver pheasant.

He once rescued three seal pups, buying them for £12 each from hunters in the Wash in 1970, before raising them in the wildlife park, while his otter, Spade, had a starring role in the 1979 film Tarka the Otter.

The Legacy: Sir Joseph Banks, the naturalist who created Kew

The Lincolnshire landowner who was described by David Attenborough as a 'passionate naturalist' and 'the great panjandrum of British science'.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Credit: Tony Evans/Timelapse Library/Getty Images

The Legacy: Miriam Rothschild, the pioneer of organic and wildflower gardening

The celebrated entomologist and Bletchley Park codebreaker was also way ahead of the times when it came to gardening.

Credit: Getty

Who was the original Jack Russell who gave his name to one of Britain's favourite dog breeds?

Kate Green takes a look at the the legacy of Revd John Russell, the man who gave his name to

Kate is the author of 10 books and has worked as an equestrian reporter at four Olympic Games. She has returned to the area of her birth, west Somerset, to be near her favourite place, Exmoor. She lives with her Jack Russell terrier Checkers.