The 1930s eco-warrior who inspired David Attenborough and The Queen, only to be unmasked as a hoaxer and 'pretendian' — but his message still rings true

Martin Fone tells the astonishing story of Grey Owl, who became a household name in the 1930s with his pioneering calls to action to save the environment — using a false identity to do so.

In late 1935 one of the hottest tickets in England was to attend a lecture given by an imposing figure of a man, tall, hawk-nosed, dressed in buckskin and wearing magnificent feathered headgear on his braided hair who, once a beaver trapper in Canada, had reinvented himself as an ardent conservationist. By the time Grey Owl had stepped off the Empress of Britain in Southampton on October 17th he was already a popular author with three books and numerous articles to his name.

His Damascene moment, according to Grey Owl’s account in Pilgrims of the Wild (1935), came when, after trapping and killing a mother beaver, he was haunted by the cries of the kittens which resembled the sounds of human babies. The following day, piqued by the protestations of his wife, Anahareo, a woman of Mohawk Algonquin descent, he went back to rescue and adopt the babies.

From that moment he railed against the cruelty of beaver trapping, a timely volte-face as numbers of beavers, valued for their waterproof pelts and castoreum, a yellowish secretion used for perfume, had plummeted to dangerously low levels in Canada. ‘Every word I write, every lecture I have given or ever will give’, Grey Owl wrote in 1936, ‘were and are to be for the betterment of the Beaver people, all wild life, the Indians, and half-breeds, and for Canada, in whatever small way I may’.

His message was simple but powerful. Canada’s greatest asset was its forest lands and the plundering of the country’s hinterland had to stop. Humans belonged to Nature not Nature to them. As well as being ahead of his time, a forerunner of modern day conservationists, his message seemed more potent as he epitomized the noble savage, possessed of a natural insight into the world around him.

Grey Owl’s lecture tour of England attracted around 250,000 people, including the Attenborough brothers, Richard and David, who queued outside a Leicester theatre for five hours to hear him. Grey Owl went on to touch their adult lives, David being inspired to become one of Britain’s foremost naturalist and conservationist while Richard went on to direct the biopic, Grey Owl, in 1999, starring Pierce Brosnan, although he claimed that it was an article in Country Life by George Winter commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of Grey Owl’s death that reminded him of his childhood encounter.

The lectures followed a similar format. After a few words of welcome, Grey Owl would show a film, Pilgrims of the Wild, about his life at Beaver Lodge by Lake Ajawaan in Saskatchewan, telling stories in a natural and engaging style and giving insights into the lives of beavers as the film ran. The diplomat, Georges Vanier, noted that ‘all those, and they are legion – who have come in contact with him, have been much impressed by his knowledge, his simplicity and by his manners who are instinctively of a gentleman in spite of his long and almost continuous life in the woods’.

The demand to hear his story proved insatiable and in the autumn of 1937 he was back in Britain giving 140 lectures, including a Royal Command Performance at Buckingham Palace on December 10th attended by King George VI and his daughters. He followed this up with a tour of North America in early 1938 but the strains of touring had taken its toll on his health.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

On April 13, 1938, at the age of 49, he died of exhaustion and pneumonia, his friend, Major J A Wood, observing that ‘at 8.25 in the morning, he died very quietly and pictures taken show that the congestion in his lungs was very slight, which all goes to prove that he had absolutely no resistance whatever’. He was buried on the ridge behind Beaver Lodge.

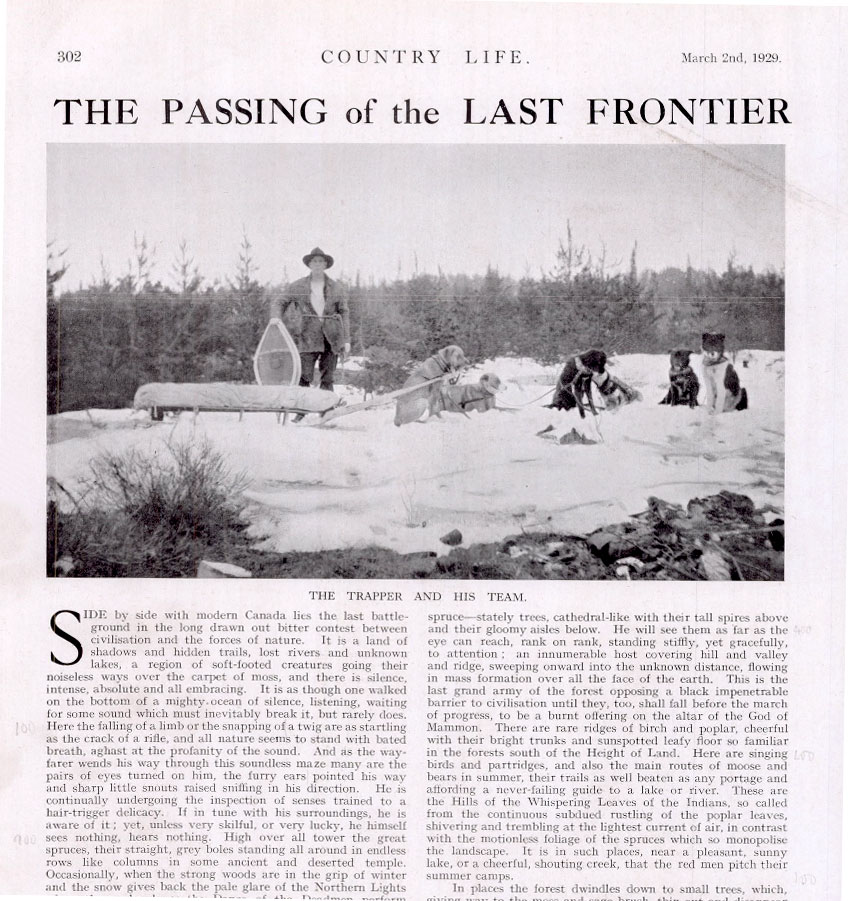

Curiously, Country Life played a significant role in Grey Owl’s early rise to prominence, being the first to publish one of his articles, The Passing of the Last Frontier, on March 2, 1929 under the byline of H.Scott-Brown, corrected a week later to Archibald Stansfeld Belaney. It also published his first book, Men of the Last Frontier (1931), under the name of Grey Owl, which became a best-seller, and kept a secret that was only divulged after his death.

Hitherto, the accepted version of Grey Owl’s origins had been that he was the son of George MacNeill, a Scotsman who had been a scout during in the 1870s in the Indian Wars in the south-western United States, and Katherine Cochise from the Apache Jicarilla band. He was born in the Mexican town of Hermosillo, where his parents, members of the Wild Bill Hickok Western Show, had been performing. His later publisher, Lovat Dickson tried to maintain this story, even in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary, in Half Breed (1939).

The North Bay Nugget, an Ontario-based newspaper, begged to differ, though, having sat on the story for three years that Grey Owl was what is now known as a ‘pretendian’, a pejorative term used in North America to describe someone who claims to be Indigenous but has no Indigenous ancestry. As soon as they had reports that Grey Owl had died, they ran a story exposing him as a fraud. The Toronto Star followed suit with the headline ‘Grey Owl Really an Englishman, Old Friends Insist’.

Journalists on both side of the Atlantic picked up on the story, quickly establishing that Grey Owl was really Archibald Stansfeld Belaney. He had been born and raised in the Sussex town of Hastings by his grandmother and two maiden aunts, Carry and Ada, into whose care his parents had left him. At the age of seventeen he fulfilled his ambition to move to Canada and disappeared into the forests of northern Canada, joining the Ojibwa People.

There he learnt their language and customs, dyed his hair black and darkened his skin using henna dye. Roaming amongst the various tribes, he met Anahareo and eventually dedicated what remained of his life to conserving the Canadian forests and protecting the endangered beaver.

The revelations about Grey Owl’s true identity split opinion as to the value of his work. Some just saw him as a fraud who had misappropriated the indigenous peoples’ voice but others were prepared to see beyond that, recognising that his romantic alter ego had gone a long way to furthering the cause of conservation and highlighting the plight of the beaver.

Belatedly, in 1997 two plaques were unveiled in Grey Owl’s honour in his home town of Hastings, one at 32, St James Street where he was born and the other at 36, St Mary’s Terrace, where he grew up. Hastings Museum has an exhibition of memorabilia and a replica of part of his Canadian lakeside cabin while a commemorative plaque can be found at the ranger station at the town’s country park.

The restoration of the beaver’s fortunes has been one of the success stories over the last few decades. From a peak of 100 to 200 million before the days of the fur trade to almost virtual extinction, the beaver population in North America has bounced back to an estimated ten to 15 million. After an absence of about 400 years beavers have been successfully reintroduced into the wild in Britain with at least 1,000 in Scotland and 500 in England. They now enjoy protected species status making it illegal to kill or harm them or interfere with their habitats.

Belaney was clearly a colourful and complex character who employed dubious methods to make his point but his heart was in the right place. After all, to paraphrase Sophocles, it is the message not the messenger that counts.

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.

-

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbinding

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbindingAn exhibition on the legendary bookbinder Roger Powell reveals not only his great skill, but serves to reconnect us with the joy, power and importance of real craftsmanship.

By Hussein Kesvani

-

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary Britain

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary BritainCourtesy of our ‘special relationship’ with the US, Spam was a culinary phenomenon, says Mary Greene. So much so that in 1944, London’s Simpson’s, renowned for its roast beef, was offering creamed Spam casserole instead.

By Country Life

-

Curious Questions: Will the real Welsh daffodil please stand up

Curious Questions: Will the real Welsh daffodil please stand upFor generations, patriotic Welshmen and women have pinned a daffodil to their lapels to celebrate St David’s Day, says David Jones, but most are unaware that there is a separate species unique to the country.

By Country Life

-

Nobody has ever been able to figure out just how long Britain's coastline is. Here's why.

Nobody has ever been able to figure out just how long Britain's coastline is. Here's why.Welcome to the Coastline Paradox, where trying to find an accurate answer is more of a hindrance than a help.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious questions: how an underground pond from the last Ice Age almost stopped the Blackwall Tunnel from being built

Curious questions: how an underground pond from the last Ice Age almost stopped the Blackwall Tunnel from being builtYou might think a pond is just a pond. You would be incorrect. Martin Fone tells us the fascinating story of pingo and dew ponds.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: What's in a (scientific) name? From Parastratiosphecomyia stratiosphecomyioides to Myxococcus llanfair pwll gwyn gyll go gery chwyrn drobwll llan tysilio gogo goch ensis, and everything in between

Curious Questions: What's in a (scientific) name? From Parastratiosphecomyia stratiosphecomyioides to Myxococcus llanfair pwll gwyn gyll go gery chwyrn drobwll llan tysilio gogo goch ensis, and everything in betweenScientific names are baffling to the layman, but carry all sorts of meanings to those who coin each new term. Martin Fone explains.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: How did a scrotum joke confuse paleontologists for generations?

Curious Questions: How did a scrotum joke confuse paleontologists for generations?One of the earliest depictions of a fossil prompted a joke — or perhaps a misunderstanding — which coloured the view of dinosaur fossils for years. Martin Fone tells the tale of 'scrotum humanum'.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Why do so many animals have bright white bottoms?

Curious Questions: Why do so many animals have bright white bottoms?Why do so many animals have such obviously flashy appendages, asks Laura Parker, as she examines scuts, rumps and rears.

By Laura Parker

-

Curious Questions: Why do all of Britain's dolphins and whales belong to the King?

Curious Questions: Why do all of Britain's dolphins and whales belong to the King?More species of whale, dolphin and porpoise can be spotted in the UK than anywhere else in northern Europe and all of them, technically, belong to the Monarch. Ben Lerwill takes a look at one of our more obscure laws and why the animals have such an important role to play in the fight against climate change.

By Ben Lerwill

-

Curious Questions: When does summer actually start?

Curious Questions: When does summer actually start?You'd think it would be simple. It's anything but, as Martin Fone discovers.

By Martin Fone