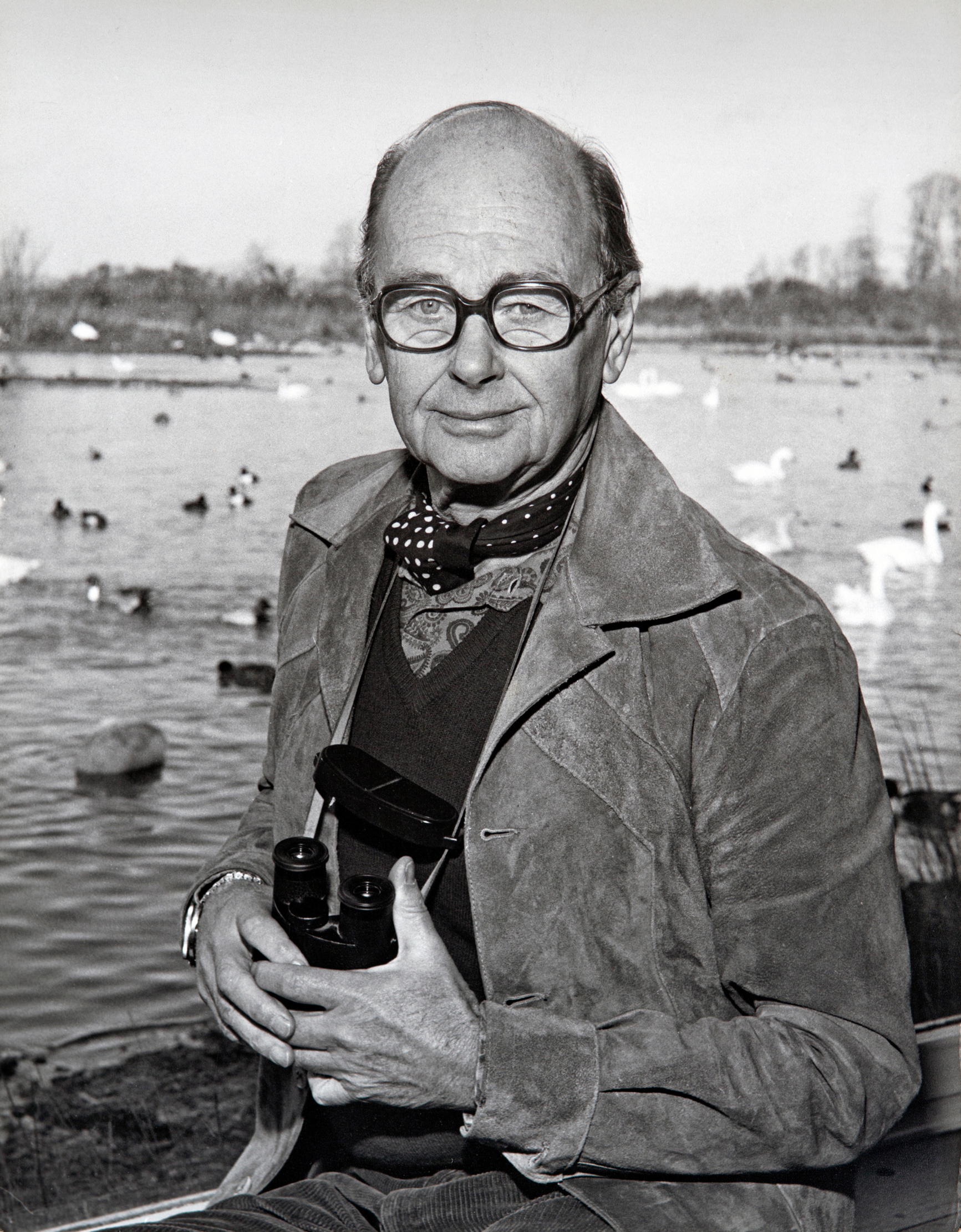

Sir Peter Scott: the Olympic sailor, national glider-flying champion and Second World War veteran who became the father of wildfowl conservation

As well as helping found the WWF and designing its panda logo, he also took part in a hunt to find the Loch Ness Monster.

Make the boy interested in natural history if you can… Guard him against indolence,’ wrote Capt Robert Scott in his last letter to his wife. Peter Scott (1909–89) was only two when his father perished in Antarctica in 1912, but that small boy grew up to engender a worldwide conservation movement, as well as being a writer (he was first published by Country Life) and artist of note.

Sir Peter (he was the first Briton to be knighted for services to conservation) was good at pretty much everything: he was the first president of the Society of Wildlife Artists, he won an Olympic bronze medal for sailing in 1936, he was a national glider-flying champion and was decorated in the Second World War.

He was also a good wildfowling shot, describing the call of the shore in Morning Flight (1935), and was enthralled by the migrant geese arriving in the Fens — ‘Like a symphony of Beethoven, their call is everlasting’ — but, in the early 1930s, a bag of some 80 pink-footed geese proved a Damascene moment: ‘The species can ill afford to lose so many individuals,’ he concluded.

In 1946, he founded the Wildfowl and Wetland Trust, with its headquarters at Slimbridge, Gloucestershire, where it remains; he helped instigate the World Wildlife Fund, designing its panda logo; is credited with saving the Hawaiian (nene) goose from extinction; and discovered from drawing Bewick swans that they had unique beak patterns. This method of identifying returning birds to Slimbridge is still used 10,000 swans and 60 years later.

He also conducted extensive research into the existence of the Loch Ness Monster. In 1961, Sir Peter joined a group convinced that it was worth looking into the existence of 'Nessie'. In 1975, against scientific hostility and public ridicule, he wrote a paper naming the fabled creature Nessiteras rhombopteryx and maintained: ‘It can never be proved that there are no large animals in Loch Ness except by draining it, which will never be done.’ In 1977, 12 years before his death, he donned a wetsuit and dived into the loch for a look

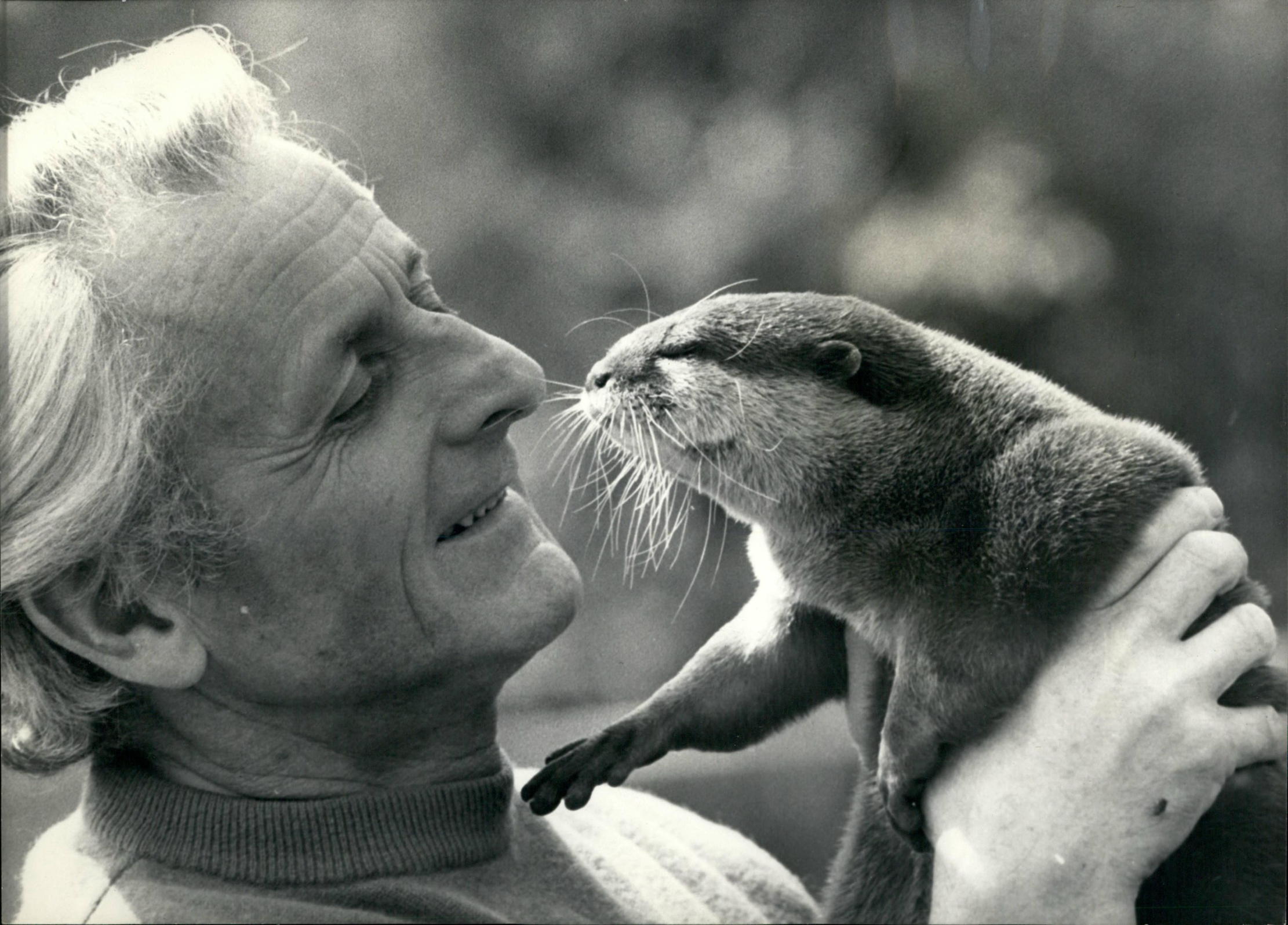

The Legacy: Philip Wayre, the man who saved the otter

The heartwarming tale of how this film-maker and naturalist restored the otter to English rivers.

The Legacy: Sir Joseph Banks, the naturalist who created Kew

The Lincolnshire landowner who was described by David Attenborough as a 'passionate naturalist' and 'the great panjandrum of British science'.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Credit: Tony Evans/Timelapse Library/Getty Images

The Legacy: Miriam Rothschild, the pioneer of organic and wildflower gardening

The celebrated entomologist and Bletchley Park codebreaker was also way ahead of the times when it came to gardening.

Credit: Getty

Who was the original Jack Russell who gave his name to one of Britain's favourite dog breeds?

Kate Green takes a look at the the legacy of Revd John Russell, the man who gave his name to

Kate is the author of 10 books and has worked as an equestrian reporter at four Olympic Games. She has returned to the area of her birth, west Somerset, to be near her favourite place, Exmoor. She lives with her Jack Russell terrier Checkers.