Rabbits: Our most underrated creature? The underground engineering and clever tricks of Britain's third-favourite pet

Pie filling, pest or pet of underrated beauty, the rabbit is a mute and gregarious commoner that will nonetheless scream, fight and kill when warranted, says award-winning nature writer John Lewis-Stempel.

Would you be a happy bunny if I rabbited on? Or shall I pull a rabbit out of the hat and hop to it? Perhaps you are caught like a rabbit in the headlights?

No surer sign of an animal’s importance exists than multiple entries in the national book of idioms. Or places named for the creature. Perhaps you are reading this article about ‘coneys’, as the European rabbit is popularly called across Britain, on Coneygar Hill, in Dawlish Warren or on Braunton Burrows?

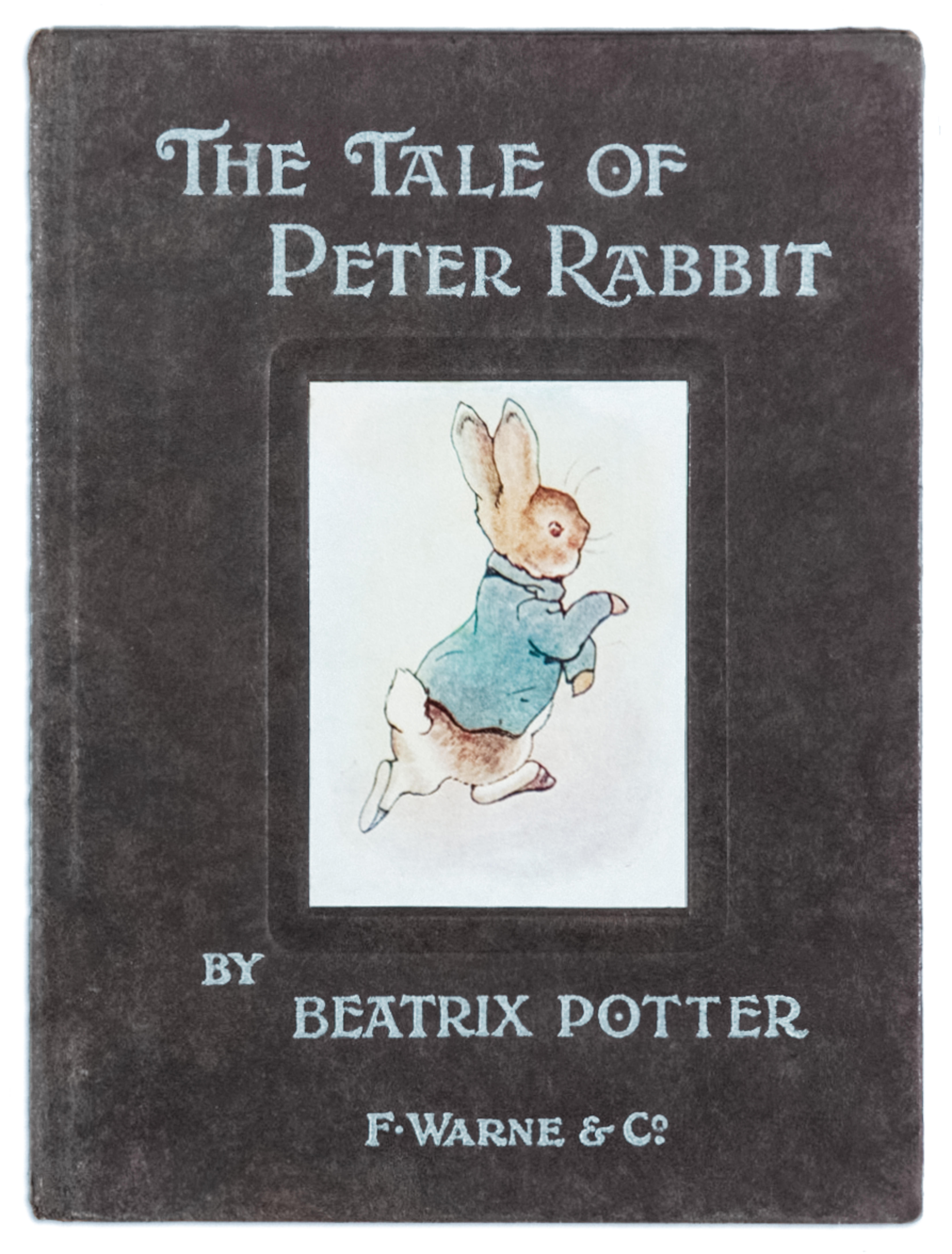

Then again, Oryctolagus cuniculus is surely unique in being so many things to so many. Emblem of Easter and bane of Mr McGregors everywhere, the rabbit is simultaneously the anthropomorphic hero of children’s books, fur-trim, pie-filler and the nation’s third-favourite companion animal. One million pet bunnies abide with us.

Hippity-hopping over the lawn in the evening, velvet nose a-twitch, the rabbit is a furry bundle of cuteness.

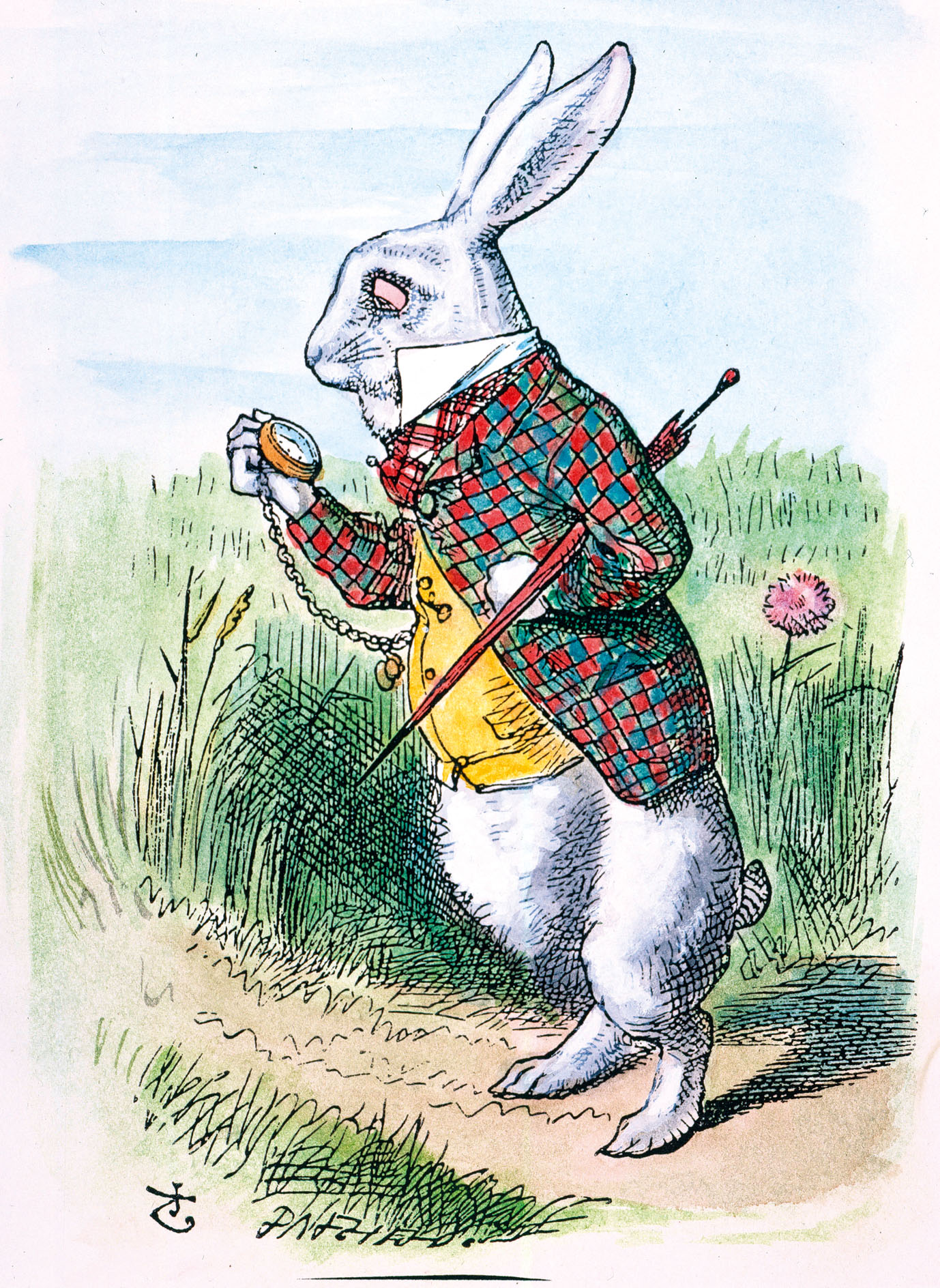

But how does such a meek being conquer the countryside? To understand the rabbit’s success story, one needs, like Alice in Wonderland, to pop down the rabbit hole.

What's the difference between a rabbit and a hare?

Despite the related looks, the rabbit is not a hare; the latter lagomorph relies for survival on speed, clocking 40mph across the earth’s surface; the rabbit manages a decent 18mph, can bound 9ft, has near 360˚ vision and independently rotating ears — not easy-peasy prey, but not truly difficult for a fox, weasel or eagle.

How do rabbits avoid predators?

For safety, the rabbit goes underground, excavating a network of tunnels or warren (work done by the female of the species, predominantly). Here, it spends most of its time when not grazing, meaning almost all the daylight hours.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

To avoid alerting prey beasts, rabbits tend to muteness, unless caught, when they pig-squeal in distress. Even in the jaws or beaks of death, not all hope is forlorn for the rabbit; a hefty and surprising kick from the hindlegs and nip from the teeth — which, incidentally, never stop growing and are ground down by grazing — can best the dread weasel. Still, despite all their senses and strategies, 90% of rabbits die in their first year and most within the first three months of life.

However, new rabbits are always on their way as deep down in the welcoming womb of the earth, a doe will birth a new litter. And another. Even when the loathsome disease myxomatosis struck in 1953, near exterminating the British rabbit, bunny leapt back and resumed its munching of Mr McGregor’s garden. Rabbit redux.

How many babies do rabbits have?

From down in its dark underground fortress, the rabbit launches its rule on the world. It replenishes its strength by the trick of re-ingesting a specific kind of its own droppings called caecotrophs, which are replete with protein and vitamin B. Then, bunny breeds in proverbially prodigious numbers; a doe or female rabbit can have as many as eight litters in a year, 14 ‘kits’ per litter — making a potential 112 in total every 12 months — and is aided in her maternity endeavours by females of the family.

Endearingly, rabbits are gregarious. They mutually groom. They cuddle together for warmth. (All qualities that make rabbits suitable as pets.) Yet bunny, behind the whiskers, is a fecund Spartan survivalist. A dominant female — and rabbit society is strictly hierarchical — will kill the kits of rivals, dragging them by the scruff of their necks to the surface to perish. Thus does Old Mother Rabbit protect the fate of the warren; too many kits playing about the place attracts predators. In overpopulated areas, pregnant does may eliminate their own embryos through intrauterine resorption.

What is mymomatosis?

In October 1953, the myxoma virus was discovered in Edenbridge, Kent, and life was never the same for the nation’s rabbits again — or our people. Although the British government had trialled myxomatosis as a means of rabbit control in the 1930s, the 1953 outbreak was accidental, crossing the Channel from France, where introduction was intentional. Many British crop growers were pleased at the killing of an agricultural pest, but the sight of tens of thousands of swelling, discharging and dying animals effectively ended rabbit as a national dish.

Despite finding a pro-rabbit champion in Sir Winston Churchill, who criminalised the deliberate spreading of the disease, myxomatosis was allowed to run its course, with a mortality rate of 99% of rabbits from the English south coast to the Shetlands. The prime vector was the rabbit flea. Shooting people deplored the loss of game, hatters and furriers the lack of fur.

Rabbit populations revived when individuals developed resistance to myxomatosis, which became endemic. However, a new imported plague, viral haemorrhagic disease (VHD), has caused a second drop in Britain’s rabbit population, being 80% lethal to infected local populations. Myxomatosis still kills rabbits as well and numbers are in decline across the country. Even the ever-resilient rabbit requires a bit of conservation effort, these days.

What do rabbits eat in the wild?

When rabbits do venture above ground to feed, they rarely wander more than 80ft from their burrow — and often with a pre-planned, closer ‘bolt-hole’ to escape Mr Fox or Old Brown. They graze quickly for the first half hour of evening eating, then more selectively for another 30 minutes. They are unfussy eaters — another reason for the historic boom and geographical spread of the species — with the bulk of the diet being grass, wildflowers and cereals. (Warner Bros notwithstanding, carrots are not favoured food for Bugs Bunnies.)

Do rabbits damage the countryside?

The rabbit suffers the injustice of all common things, in that its beauty is overlooked — a rabbit’s fur is a complex wonder of bronzes and silvers — and its value under-estimated. Having been platter provision, clothing, pest and pet, the rabbit carries another portfolio today. Environmentalist. Where rabbits have nibbled and scratched over the centuries, they have created a special environment of shorn grass and warm, bare earth that is a haven for rare flowers and basking reptiles.

Rare flora abetted by bunny-grazing include the prostrate perennial knawel, Scleranthus perennis ssp. prostratus, which exists nowhere on the planet outside Norfolk’s rabbity Breckland heaths. The loss of wild rabbits after myxomatosis contributed to the extinction of the large blue butterfly in 1979.

Next time you see that twitching velvet nose, tip your hat to the great survivor, prime prey on paws and eco-engineer of the British countryside that is the humble rabbit.

Are rabbits a native species in Britain?

The rabbit's record in Britain is astonishing for a relatively recent arrival to our shores — or, rather, a re-arrival. Britain had its own native population of rabbits before the exterminating Ice Age and the animals were reintroduced by the Romans, but failed to flourish, only to be imported in the 12th century by the invading Normans.

Native to the Iberian peninsula and south- west France, the rabbit was widely kept in Ancient Rome — where kits were a delicacy — and then by monasteries, likely because the Catholic Church deemed young rabbits were not meat, but fish and could, therefore, be eaten during Lent.

The pagan Vikings, on becoming settled Christian ‘Northmen’ in France, took up the rabbit habit; the Bayeux Tapestry depicts Norman soldiers carrying rabbits in sacks and crates to England, where the animal was raised in walled enclosures or warrens, some 1,000 acres in extent. (At first, the delicate rabbit could not dig burrows in wet, cold English soil, so they were made for it by drilling with augers.) The warren was cared for by a ‘warrener’, who lived in a lodge, often fortified, from which he protected his charges from predator and poacher alike.

Rabbit meat was so prized that it could only be afforded by the rich; in 1465, when George Neville was installed as the Archbishop of York, 4,000 rabbits were provided for the celebratory bash. The animal’s fur was equally sought after. Henry VII favoured black-rabbit fur from Norfolk to line his night attire. Over time, the rabbit fur industry grew (especially in East Anglia), notably with the making of felt headwear by glueing rabbit hair with shellac.

The rabbit proved impossible to confine and, outside the Norman warren, multiplied exponentially, thus reducing its own worth. In the 13th century, the market price of the rabbit carcase averaged a luxurious 3½d, plus a further penny for the skin. Two centuries later, the price had fallen to 2¼d. By the 18th century, it was fodder for the poor, and by the 1950s, the British countryside pitter-pattered under the paws of 100 million individuals.

Credit: www.setouchitrip.com

Bucket List inspiration: Okunoshima, the small island in Japan occupied by hundreds of adorable bunnies

Rabbit Island is a well-kept secret along the Japanese coastline, providing sanctuary for hundreds of wild rabbits and an exciting

Recipe: Confit rabbit and wholegrain-mustard pie that's sustainable and healthy

Chef Steven Ellis shares this delicious recipe for a classic winter dish: rabbit pie.

The enduring appeal of Peter Rabbit

Beatrix Potter's most famous creation, Peter Rabbit, remains as popular as ever, despite his genesis being well over a century

Need to Know: Pests, Vermin and other Undesirables

Elizabeth tackles the tricky issue of controlling pests such as rabbits and pigeons on private land