Oystercatchers: The 'hammerers and stabbers' of the avian world, who can live into their 40s

An evocative symbol of our coast, with its shrill call and pied plumage, the oystercatcher is actually more fond of feeding on limpets, discovers Vicky Liddell.

It’s the call you hear first — a shrill, insistent peep, peep — but, once sighted, there’s no mistaking the striking pied plumage of the oystercatcher, Haematopus ostralegus. Garrulous and well-dressed, with pinkish legs and a comically long orange bill, oystercatchers are party animals and can often be seen running up and down the beach in a constant state of excitement.

Originally called the sea pie, the name oystercatcher — which started to appear in the late 18th century — is something of a misnomer. Although the bird is capable of cracking open an oyster, it mostly feeds on limpets, mussels, crabs, cockles and, during the breeding season, earthworms and caterpillars.

Oystercatchers are visible throughout the year, but are particularly noticeable in winter when their numbers are swelled by the arrival of birds from Iceland and Scandinavia. At Morecambe Bay in Lancashire, where the vast intertidal mudflats provide a seafood banquet unequalled elsewhere, there’s an estimated winter population of 50,000 birds.

'If a bird moves area and begins to feed on different prey, their bill quickly adjusts — a hammerer might become a stabber within a fortnight'

Yet, despite this impression of abundance, the oystercatcher is still classed as vulnerable in Europe and at amber status in the UK, where 50% of the entire population is restricted to 10 or fewer sites. ‘Their main threat is disturbance from humans, especially at high tide when the birds are resting,’ laments Amy Hopley, wildlife officer at the Morecambe Bay Partnership, which has appointed ambassadors who ask the public to keep their distance and their dogs on leads.

Oystercatchers specialise in either crunchy or soft-bodied prey, to which their beaks adapt. ‘Stabbers’ get hold of a mussel and stab at the join to prise it apart, whereas ‘hammerers’ develop a thicker bill in order to smash open shells and ‘tweezers’ — mostly female birds — are more adept at probing for worms. If a bird moves area and begins to feed on different prey, their bill quickly adjusts — a hammerer might become a stabber within a fortnight.

Their distinctive, sword-shaped beaks also double up as a useful tool for stealing food from other species — oystercatchers obtain an impressive 60% of their food by attacking other waders and flying off with their lunch.

They can eat as many as 500 cockles a day, which has led them into conflict with the fishing industry. In the mid 1970s, despite a public outcry, a disastrous cull of birds was carried out, after which cockle stocks collapsed. It turned out the oystercatcher performs a valuable service by weeding out the weaker and older cockles.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Breeding pairs return to the same territories between March and May, where, after some noisy courtship calls and a period of nest dancing, in which small stones and sticks are hurled over the shoulder of the performing bird, three or four light-brown, speckled eggs are laid. Incubation lasts about 27 days and, just before hatching, the parent converses with the chicks inside the eggs via soft chucking noises. The chicks have black crowns and grey legs, and hatch out fully feathered, eyes open and ready to run — yet they are completely dependent on their parents for food for three months or more. Nests are made on open ground among sand dunes and shingle beaches, but an increasing number are choosing to breed inland.

In Scotland, which has seen an alarming 37% decrease in oystercatchers over the past 25 years, the Working for Waders initiative is educating farmers on ways to improve nesting habitat for all waders, as well as sea pies.

‘There’s no one reason for the decline in numbers. Predation by foxes and crows, disturbance and high-density grazing all play their part, but small changes in one valley or glen can have a big difference on the ground for the birds,’ explains Prof Davy McCracken, co-chairman of Working for Waders.

‘This might involve reducing grazing pressure to prevent egg trampling or not rolling the fields until the end of June. Oystercatchers are loyal to an area and the Scottish uplands are their natural breeding habitat. They don’t want to fly extra miles to a nesting place further south and run out of energy in the process.’

In other parts of the country, the oystercatcher is holding its own and the fact that the parent collects food for the chicks has opened up unusual breeding opportunities away from natural predation. Roundabouts, airports and building sites have all hosted nests and, in Aberdeen, gravel-topped flat roofs of 1960s housing blocks are home to an estimated 200 pairs. Last summer, one pair even raised chicks at a household recycling centre in Harrogate, North Yorkshire.

Bold and tenacious, breeding oystercatchers often stand their ground in the face of cattle and sheep. They’re also long-lived, with some birds surviving to the age of 30. One bird shot in France in 2017 was estimated to be at least 43. The noisy return of oystercatchers to their nesting areas is one of the first signs of spring; their watery whistle rising up above the roar of the sea is an evocative staple of the coastal soundscape.

Catch me if you can: Five things you never knew about oystercatchers

- An oystercatcher’s bill can grow at a rate of 1⁄50 of an inch every day — three times the speed of human fingernails.

- Breeding females sometimes dump eggs in other birds’ nests, as the cuckoo does, although these are rarely successfully incubated.

- Piping parties of up to 30 birds can sometimes be seen performing in a ritual dance, which involves running around in a circle with their beaks close to the ground.

- Oystercatchers emit a wide range of calls, including a social keep keep, a cock’s mating cry of a single drawn out peep, peep and a sharp pik, pik when a bird is disturbed in the nest.

- Don’t be fooled by the starling’s tuneful repertoire, which features a very convincing impersonation of the oystercatcher.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

What's a 'wellness village' and will it tempt you back into the office?

What's a 'wellness village' and will it tempt you back into the office?The team behind London's first mixed-use ‘wellness village’ says it has the magic formula for tempting workers back into offices.

By Annunciata Elwes

-

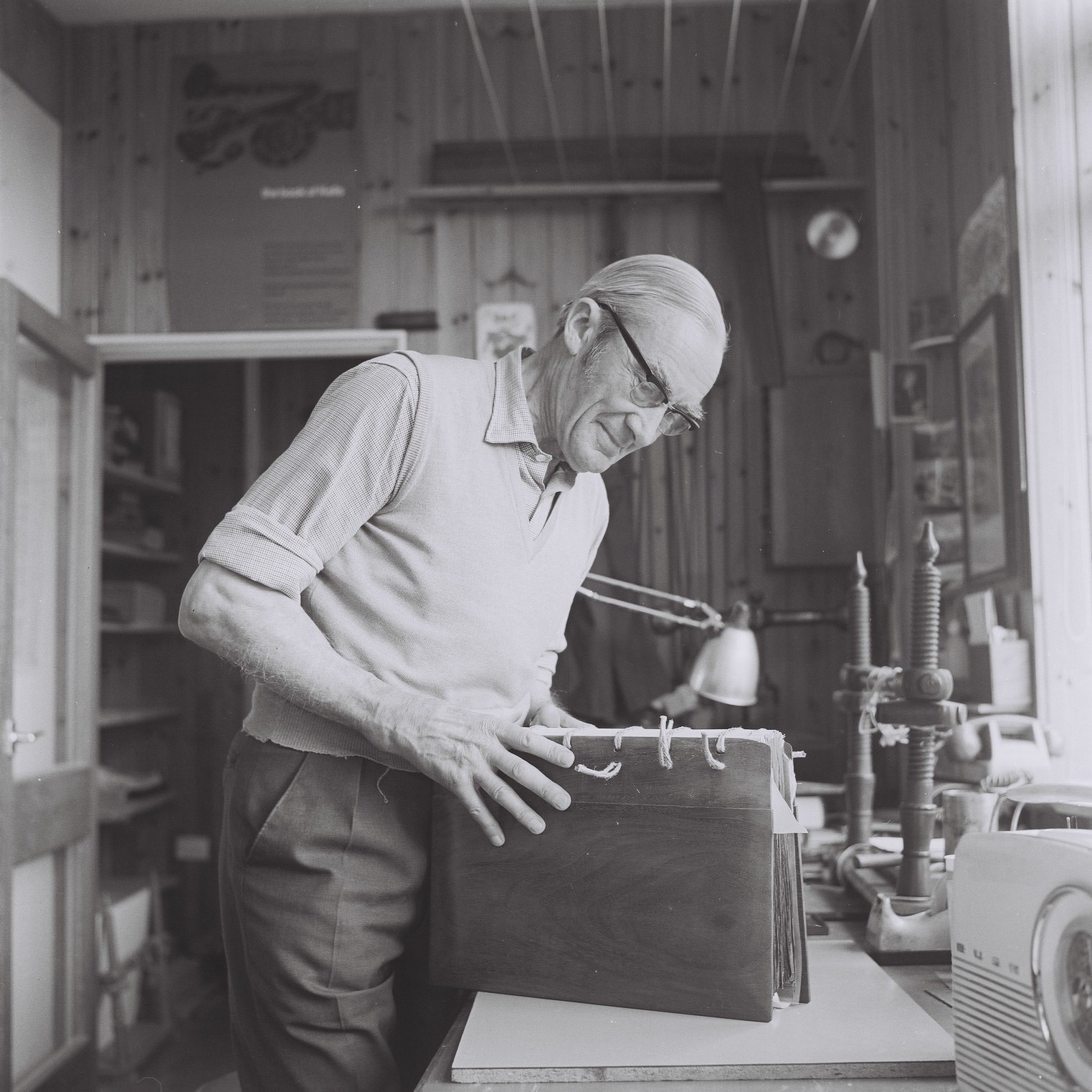

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbinding

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbindingAn exhibition on the legendary bookbinder Roger Powell reveals not only his great skill, but serves to reconnect us with the joy, power and importance of real craftsmanship.

By Hussein Kesvani