Nature's most dangerous journey? The lifecycle of the salmon

A miracle of Nature, the salmon braves body changes, hungry seals and forbidding waterfalls on its extraordinary journey to and from its spawning grounds. But now, warns Simon Lester, it may be facing one challenge too many. Illustrations by Alan Baker for Country Life.

I’m standing alone, thigh deep in a sparkling, peat-tinted Scottish river, fuelled with the anticipation of that tug on the drifting line, followed by the exhilarating passage of play, the first sight and the successful landing of the king of fish, the wonderful Atlantic salmon, aka Salmo salar. Once you’re hooked, the desire to be on your own on a deserted riverbank — an experience at once thrilling and peaceful — only gets stronger, which is why it has beguiled fisher folk for hundreds of years.

It’s the fish that drives this obsession. As shoals of fry weave at your feet and, a yard away, a mighty silver-scaled giant leaps — as does your heart — you find yourself marvelling at the salmon’s incredible life cycle. These migratory fish are anadromous: they hatch out in freshwater, but spend the majority of their lives in saltwater before returning to rivers to breed. Having spent up to four or five years at sea, their urge to reproduce is strong and they set out for their spawning grounds, their navigation assisted by the earth’s magnetic field. When they approach the coast, their senses take over, the taste of their home water guiding them back to the very location where they hatched. This protracted journey, which has gone on for millennia, is full of perils: salmon are food and must run the gauntlet of a multitude of obstacles to survive, so much so that, out of 5,000 eggs, only five adults may make it back home.

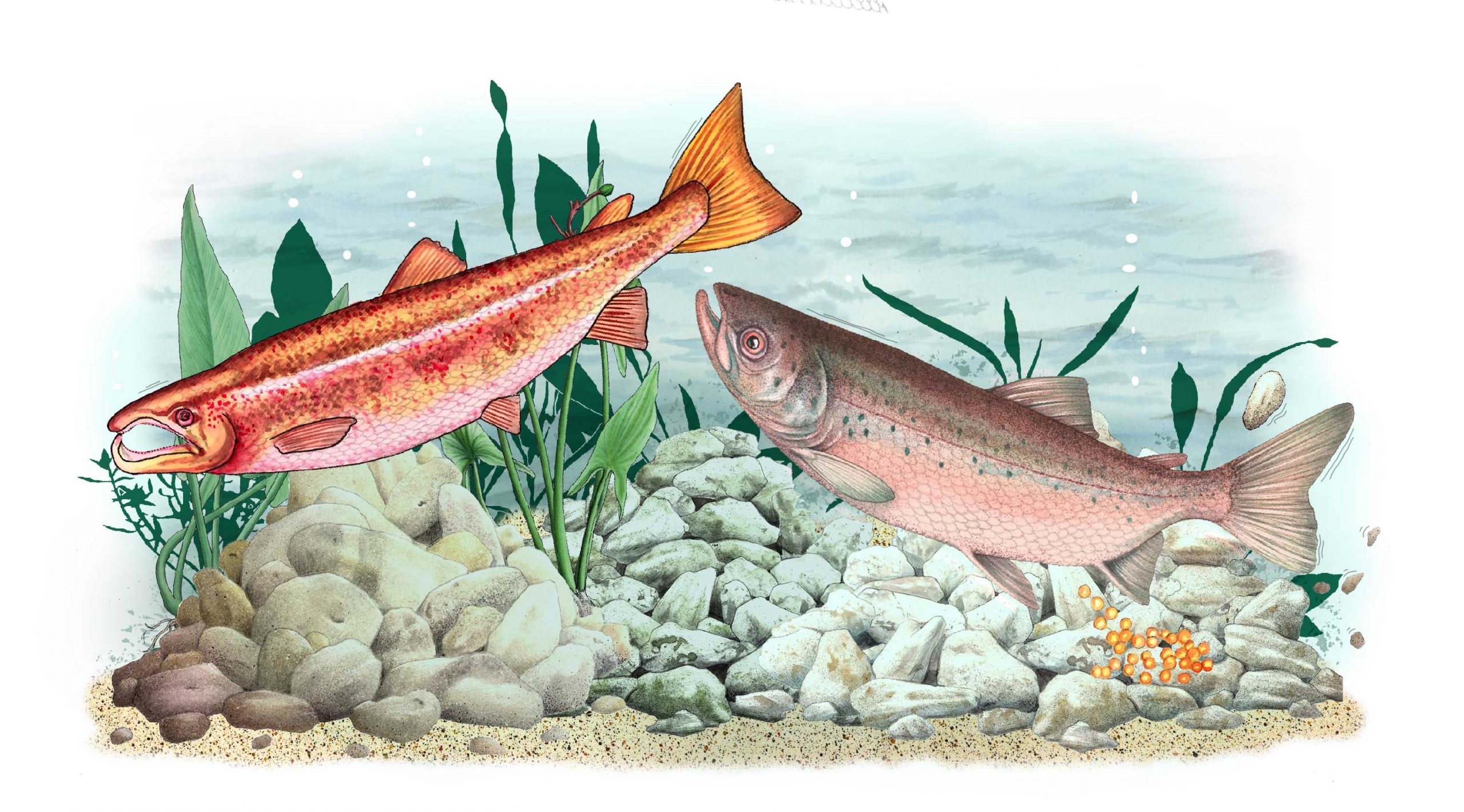

The fish’s eggs are laid in the gravel beds of the headwaters of the main rivers. The hen salmon, using her tail, makes a small depression in the gravel known as a redd; she then deposits her reddish-orange charges from her swollen form — there are up to 800 per Ib of her weight. The cock fish, in his breeding tartan colours, lurks nearby, equipped with his brutish kype (an extended, hooked lower jaw). He releases his milt as soon as the eggs are laid, after which the hen fish deftly covers them with gravel. Developing over a period of two to six months, with the water temperature dictating the timing, the eggs hatch in spring, leaving a tiny fish attached to a large yolk sack, which acts as a packed lunch. Only an inch long, the critters lie low, sheltering in the gravel, trying to keep out of harm’s way, until their yolk sac is exhausted and they must start to look for food.

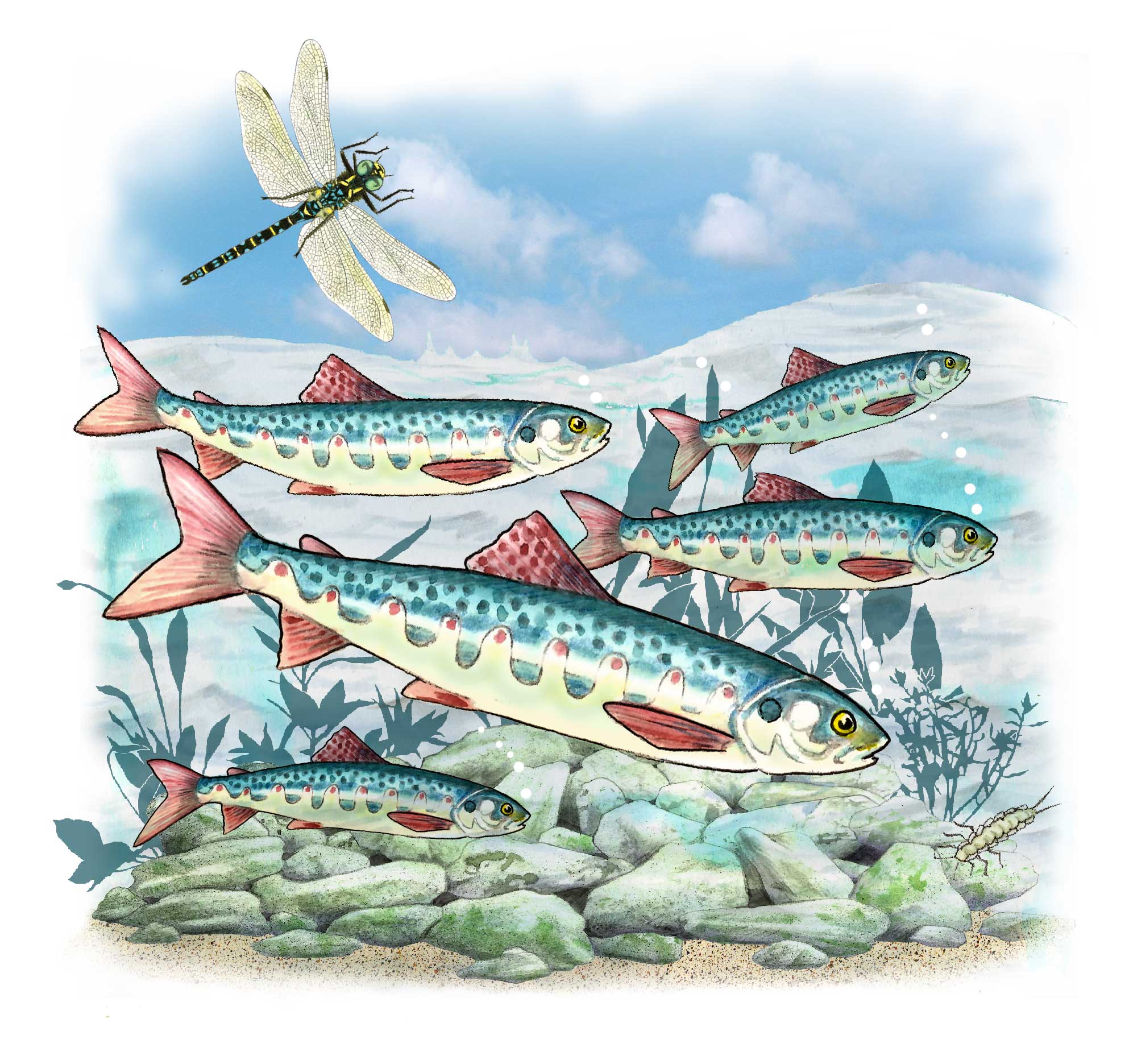

As they enter the third stage of their life cycle, these little fish become fry. However, to negotiate life in the river, they must swim to the surface and take a gulp of air to fill their swim bladder. The fry move downstream of the redds, as they cannot swim against the current, and shelter in the shallows, feeding on small invertebrates, the high-protein diet speeding their growth. In these early stages, flooding, drought and predators all hamper their survival rate — wild brown trout hoover up a lot of tiny fish, as can the darting kingfisher.

At 2in long, the fingerlings, or parr, have all their fins and scales and their camouflage improves. Dark vertical bars running like finger marks along the length of a body punctuated with red and black spots makes for a very pretty little fish and, crucially, they blur its profile, helping it to blend in with its surroundings and avoid being eaten — the parr make a tasty morsel for grey herons, cormorants and the fish-eating ducks, goosanders and mergansers. By now, however, the fish are hunters themselves: their diet is entirely carnivorous and they will break the surface of the water to take low-flying and waterlogged invertebrates.

Depending on the conditions within the river, food supply and an optimum water temperature of 16˚C-19˚C, the timings of when the parr feel the call of the wild and start to prepare for their migration downstream to the sea will vary—it could easily be four years.

Having doubled in size, the fish begin the change from freshwater past to ocean future when they enter the smolt stage. Their body becomes more streamlined and, losing its camouflage, it turns silver. The smolts move downstream — together, to confuse predators — towards the brackish estuaries. This is where the 8in-long animals experience their greatest physiological change: osmoregulation. The estuary water helps them to adjust to the dehydrating effects of saltwater: as they drink, their kidneys handle the salty mix, aided by a complex process within their gills.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Once all this is done — it can take several weeks — the glistening schools make a dash for the open sea on an ebbing tide in the cover of darkness, heading north towards the Arctic circle.

The Atlantic ocean becomes their home for several years. The salmon feed hard and grow fast, the only exception to this being the grilse, a ‘bar of silver’ that returns to its freshwater home after one winter at sea. The food-rich areas of Greenland and the Norwegian sea are their destinations: there, they eat capelin, krill, shrimp and all manner of smaller fish; in turn, they are hunted down by large predatory fish.

Historically, life at sea was free from human exploitation, but salmon then became a valuable commodity, hunted by an ever-increasing number of high-tech fishing vessels, which hoovered up massive amounts of maturing salmon. This peaked in the 1970s, when 12,000 tonnes of Salmo salar were harvested. Today, this figure has declined to about 1,000 tonnes, partly because of restrictions, but also because, in the past 25 years, the species saw a massive 70% overall decline.

After years at sea, it is time for the fish to return to their river of birth — the most hazardous trip of their lives.

When they reach the estuaries, they must reverse their bodies to freshwater mode; at this point, they stop drinking water and feeding, relying on their body condition to power them for the rest of their upstream journey. During this transition, they are ambushed by dolphins and seals that lie in wait for their forthcoming meal ticket. Once they reach fresh water, the gleaming fish may be carrying a few passengers — sea lice, hanging on for two or three weeks before they drop off.

The fish need a good flow of water to move upstream and, as they get higher up, they can often get stranded in deep pools before the next rainfall allows them to navigate the shallows. I have taken great pleasure in shining my torch at night to see the dark silhouettes as the salmon near the end of their 4,000-mile migration and have heard stories from the old boys of Langholm, in south-west Scotland, about pools so black with fish that you could walk over the river — the Border Esk — on their backs.

Sadly, I have also heard tales of foul hooking and other nefarious ways of wangling salmon. The concentration of fish in these pools makes poaching easy and this has been and continues to be a big problem for salmon and sea trout throughout the UK.

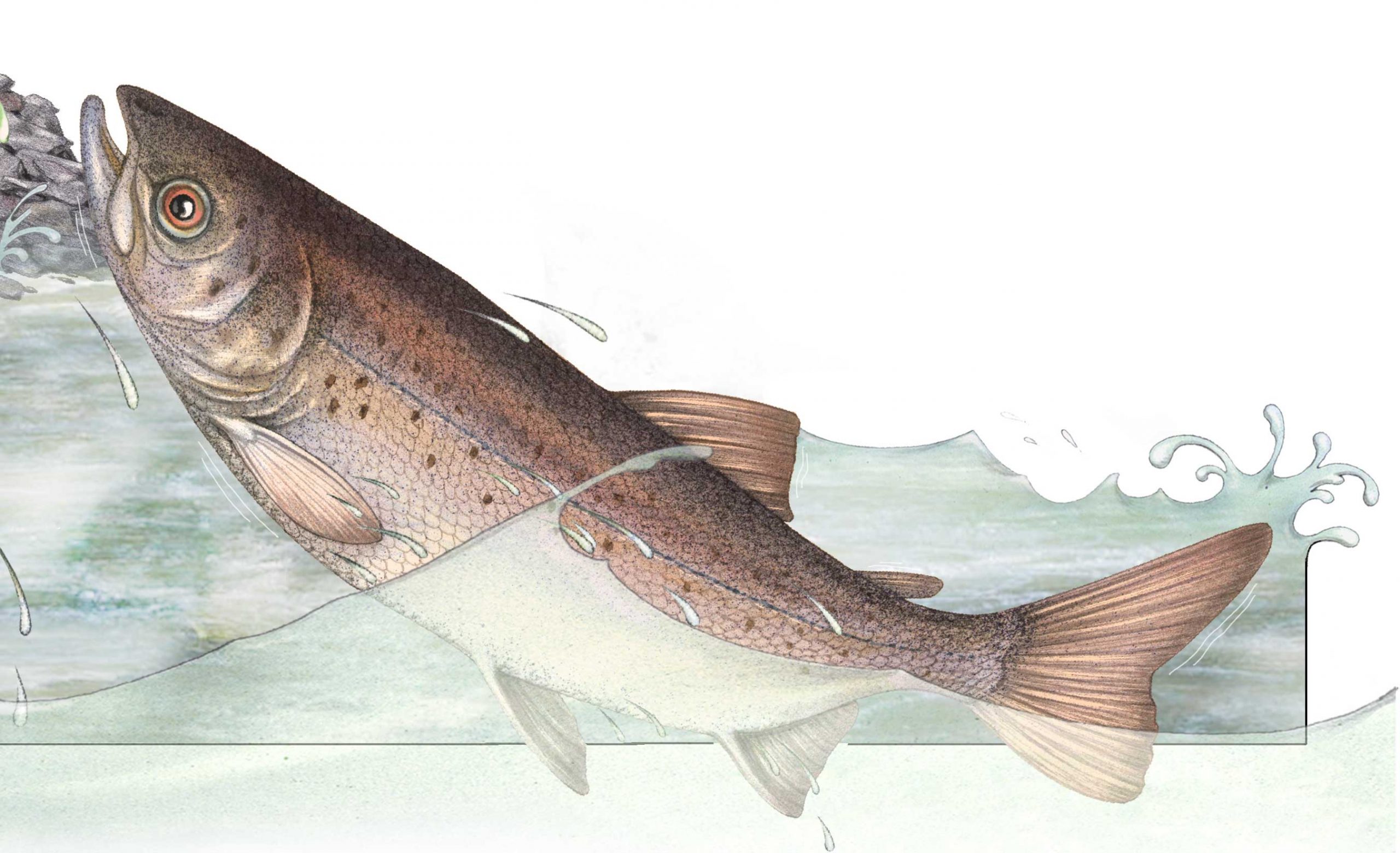

Higher and higher Salmo salar push upstream, leaving the main rivers for the tributaries that feed them. Not only does the fish have to survive natural predators, nets and thousands of fly-fishing anglers; to reach their destination, they must also overcome manmade weirs or natural waterfalls. Leaping salmon is a wildlife spectacular, their 12ft jumps illustrating the power and drive of this athletic fish. By now, they’re nearly home, but the narrow headwaters make hunting easy for otters — the only animal that can take on a full-grown salmon — and the evidence of this are the scales and bones strewn on the banks.

Once salmon reach the redds, the next generation of fish undertake the entire exhausting cycle again. Once the eggs are laid and fertilised, the older fish are spent, their performance complete. In the final stage of their life, they become kelts, of which 95% perish.

Yet, despite the great lengths to which they go to breed, the wild salmon is now facing one odd too many. At one time, the fish would have been present in most British rivers, so abundant that they fed common folk and their animals, It is nothing short of a tragedy that this noble animal has plumbed to such depths that it is off the menu, replaced by the controversial farmed salmon that has arguably contributed to the wild variety’s demise.

Pinning down the exact reasons for a species’ decline is always difficult, but when animals have such a complicated life cycle as salmon do, it is more so, as their lives unfold across many different environments.

Lately, human exploitation has decreased and natural predation has risen, although these two factors barely compare with the devastating impact that pollution from all manner of human activity can have on salmon throughout its life. All these issues are exacerbated by climate change, the floods or droughts that affect the redds and the microplastics and warming seas that alter the fish’s food chain. However, whatever the balance of causes, the end result is that, unless drastic action is taken, both ends of the salmon’s life — as well as all the stages in between — are in mortal danger.

Jonathan Self: The simple key to a life full of joy and happiness and free of care

An encounter with a 21st century goatherd makes Jonathan Self wonder if things might one day again be simpler.

Jason Goodwin: How to fill the Sycamore Gap

Our columnist on how some good might come out of the felling of the sycamore in the gap.

John Lewis-Stempel: Why autumn is the time to go nuts

Whether enjoyed as a healthy snack or deployed as the playground weapon of choice, nuts are versatile, abundant and plentiful

-

Having a ruff day: Kennel Club exhibition highlights the plight of vulnerable spaniel breeds

Having a ruff day: Kennel Club exhibition highlights the plight of vulnerable spaniel breedsPhotographer Melody Fisher has been travelling the UK taking photographs of ‘vulnerable’ spaniel breeds.

By Annunciata Elwes

-

The battle of the bridge, Balloon Dogs and flat fish: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 15, 2025

The battle of the bridge, Balloon Dogs and flat fish: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 15, 2025Tuesday's quiz tests your knowledge on bridges, science, space, house prices and geography.

By James Fisher