Jason Goodwin: The £9 million-per-pylon removal programme has begun, and it's already revealed bizarre secrets

Our columnist writes about the unsuspected secrets revealed by a project to rid our prettiest skylines of electricity pylons.

We thought for a while that they were prospecting for oil. The table by the road with the splendid vegetables for sale disappeared. A line of dilapidated fencing was replaced by a mysterious stockade of crossed chestnut palings draped with black netting. A company sign went up, a lot of chippings went down and more Land Rovers and white vans were parked on the hardstanding every day.

Finally, a huge yellow earth mover lumbered out onto the hill where it seemed to get stuck and, the next time I drove by, the grass had been scraped off an area the size of a football pitch. The spoil was neatly stacked over the strip lynchets.

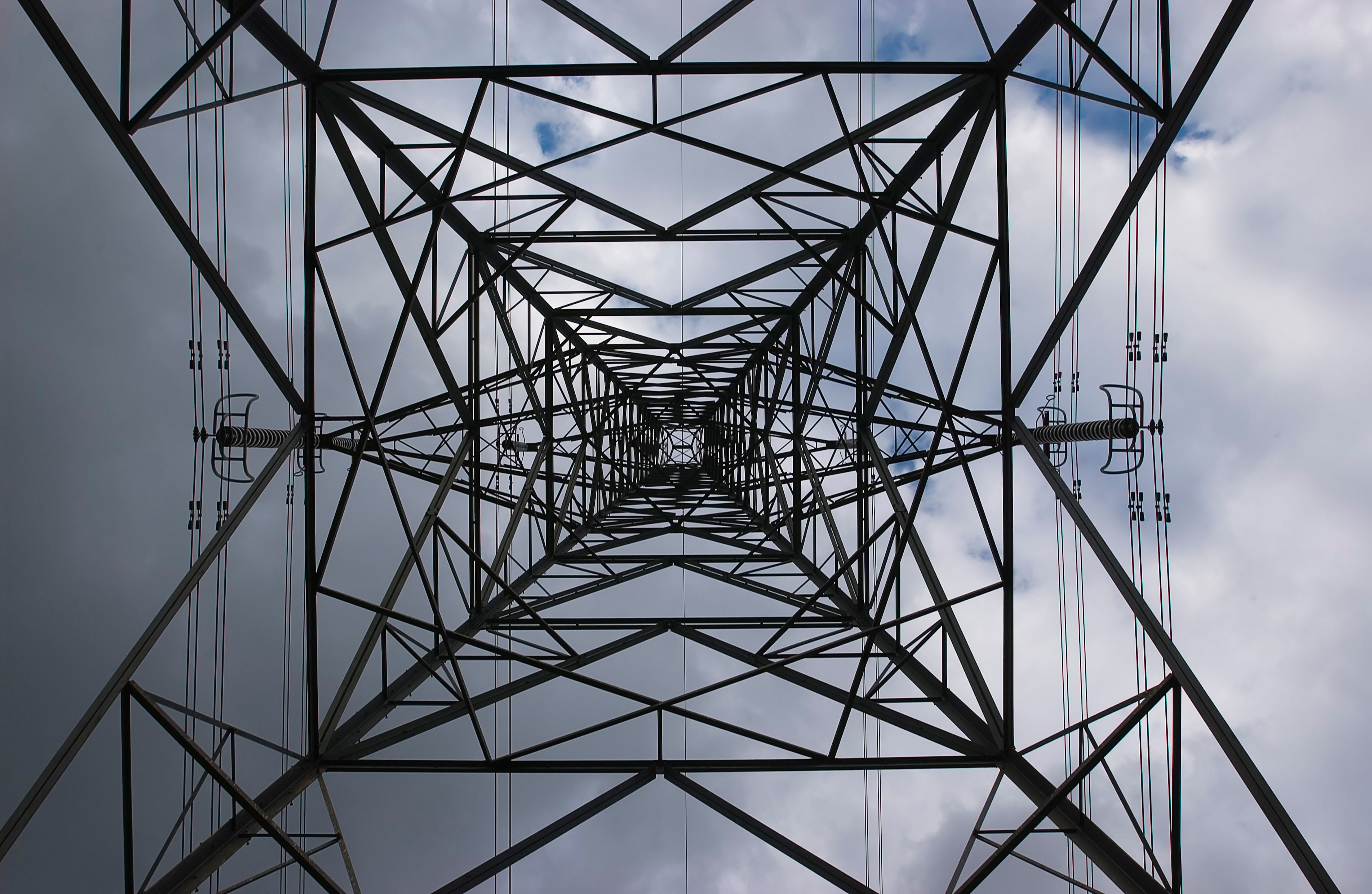

It isn’t oil, as it turns out, but the National Grid embarking on its project to get rid of the electricity pylons that stride across this Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. Hundreds of millions of pounds — putting 22p on everyone’s bill — have been allocated to remove about 45 pylons from Snowdonia, the Peak District, the New Forest and the Brecon Beacons, as well as various AONBs, such as ours. Going underground apparently means digging a 165ft-wide trench, 6ft deep. It’s a big undertaking, but nothing compared with the original task of electrifying the country in the 1920s, when 100,000 men slung 4,000 miles of cable across Britain in only five years.

'The odd thing, Jim says, is that his spine had been deliberately removed and replaced with an antler'

The first pylon — the word archaeologists gave the gateways into Egyptian temples, taken from the Greek for gate — went up in Scotland, near Falkirk. The design was settled by an anti-Modernist architect, Sir Reginald Blomfield. ‘Over-elaboration, for whatever reason, is to be deprecated, and true adherence to the strict engineering requirements will seldom result in a structure which will offend the eye.’ Some hope.

The National Grid was summoned into being in 1926, the year of the General Strike. It was the single biggest peacetime building project that Britain had ever seen, with a Tory government creating a nationalised infrastructure in the teeth of opposition from local electricity generators and country lovers such as Kipling, Maynard Keynes and Galsworthy, who shot off despairing letters to The Times.

Others found it all exciting. The sculptor Barbara Hepworth was inspired by seeing ‘pylons in lovely juxtaposition with springy turf and trees of every stature’ from the window of her electric train. In the 1930s, Stephen Spender wrote them an ode, The Pylons:

The secret of these hills was stone, and cottages Of that stone made, And crumbling roads That turned on sudden hidden villages.

He was much mocked for picturing pylons as ‘pillars/Bare like nude giant girls that have no secret’. Julian Symmons called him a ‘Pylon-Pitworks-Pansy’ poet, together with Auden, Louis MacNeice and C. Day Lewis.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

I shall be better informed now that my friend Jim has gone and got a job driving tractors for the contractor. Once the topsoil is stripped back, he says, the archaeologists move in, looking for disturbance, circles of infill that show up a different colour from the chalk. Some will be ancient barrows, the silhouettes of which were long since lost to the plough and the rain.

For as these prophets of modernity are coming down in order to restore a familiar, pastoral vision of the countryside, free of industrial blemish, something weirder, older than either, is emerging from the ground.

From one of the lost barrows the archaeologists have recovered the skeleton of a man, knees drawn up to his chest, buried at a tilt, head down, 5,000 years old. The odd thing, Jim says, is that his spine had been deliberately removed and replaced with an antler. Perhaps Spender was right about the secrets.

Jason Goodwin: In memory of Norman Stone, my tutor, guide, world traveller — and friend

Jason Goodwin pays tribute to an old friend and mentor.

Jason Goodwin: 'Politicians need historians as much as kings need minstrels'

Jason Goodwin undertakes a family cycle ride along the Danube.

Credit: Tim Gainey / Alamy Stock Photo

Jason Goodwin: ‘The only sounds were the yawning of dogs, the spitting of logs in the fireplace and the occasional papery gulp of somebody turning a page’

Snowed in and without power, Jason Goodwin was left to live a medieval lifestyle that was rejuvenating and romantic... but

Credit: Alamy

Jason Goodwin: The unbeatable 10-minute, £10 haircut — and who cares what it looks like at the end?

More speed, less fuss. What more could you ask for from a barber, asks Jason Goodwin.

-

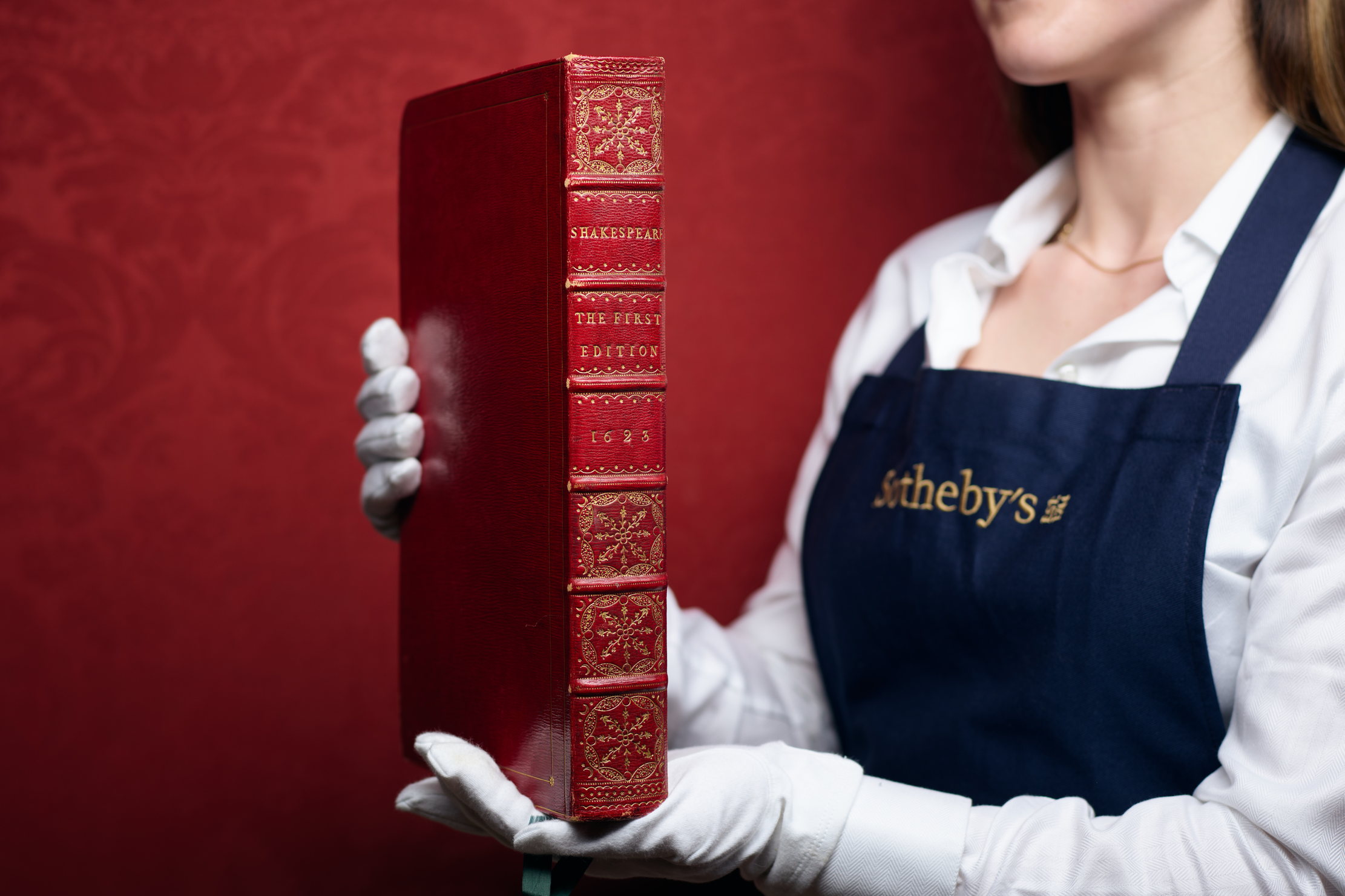

Folio, Folio, wherefore art thou Folio? Shakespeare set to be auctioned by Sotheby's

Folio, Folio, wherefore art thou Folio? Shakespeare set to be auctioned by Sotheby'sFour Folios will be auctioned in London on May 23, with an estimate of £3.5–£4.5 million for 'the most significant publication in the history of English literature'.

By Lotte Brundle

-

Damon Hill's former home in Marbella is the perfect place to slow down

Damon Hill's former home in Marbella is the perfect place to slow downThe glorious Andalusian-style villa is found within the Lomas de Marbella Club and just a short walk from the beach.

By James Fisher