11 things you never knew about the jackdaw, the bird that just loves people

Ian Morton takes a look at the jackdaw, a bird with a real affinity for man – despite a chequered reputation in our history and literature.

Jackdaws are pleasing to watch. Solemnly and methodically, they stalk the lawn, unhurried in their search patterns, neat and tidy and dignified in their bearing. Unlike the larger and clamorous cousins with which they often flock, their phrases are clipped, their conversations brief.

They pair for life, share food and, when the male barks his arrival at the nest, the female responds with a softer, longer reply. They like manmade structures. Formerly a nuisance as they favoured chimneys for their twiggy bundles, they’re less troublesome in the era of central heating and their liking for church steeples has long been indulged. As the 18th-century poet William Cowper put it, ‘A great frequenter of the church, Where bishop-like, he finds a perch And dormitory too.’ For this habit, the bird was deemed sacred in parts of Wales.

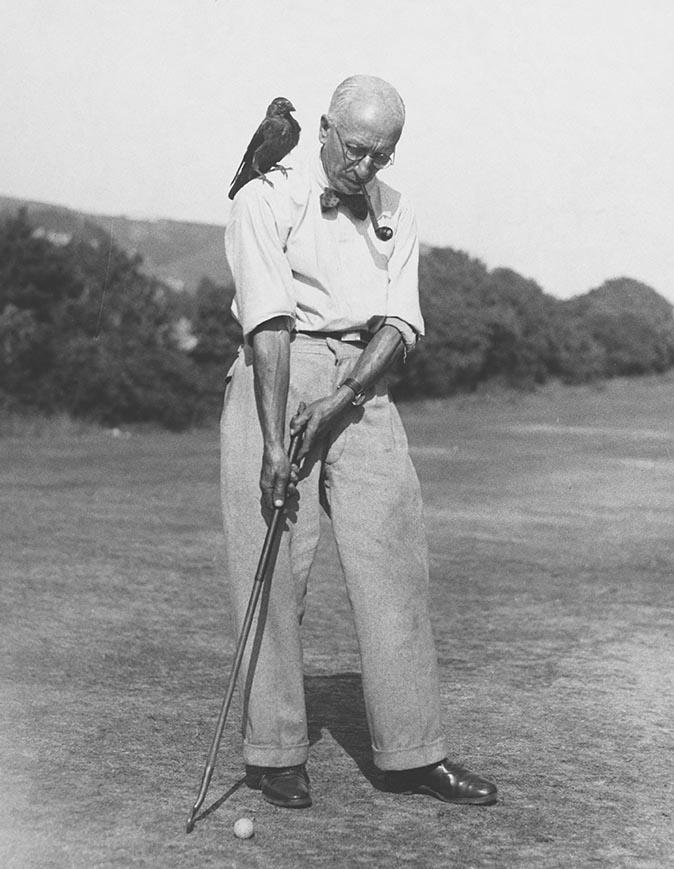

Jackdaws love people, and probably because they love eye contact

People and jackdaws get on – there’s a certain empathy between them. Many are the stories told by individuals who scooped up stranded fledglings in need and were rewarded with a bemusing trust and friendship. Jackdaws recognise human faces and studies by Cambridge zoologist Auguste von Bayern concluded that they respond to human expressions.

These corvids communicate via their eyes, just as human eye contact plays a major role, and a bird confident with its mentor can ‘read’ that person’s eye motions and will follow them to find hidden food. This interplay has encouraged and enabled research.

They can ‘marry’ to boost their status in society

From the 1930s, the Austrian ornithologist Konrad Lorenz, founder of modern ethology, determined a strict social hierarchy within jackdaw groups (collectively called trains or clatterings). Unpaired females rank lowest in the hierarchy: they’re the last to have access to food and shelter in times of scarcity, and are liable to be pecked at by others without being permitted to retaliate.

However, when a female is selected as a mate, she assumes the same rank as her partner and is accepted as such by all others in the group, upon whom she may impose her status by pecking.

They regularly make same-sex love matches – particularly in captivity

Dr Lorenz also discovered that, although the birds normally pair for life, jackdaws in captivity tend to form same-sex pairs. Research in the Netherlands in the 1970s went a step further by concluding that such pairings occur in the wild and that among females that have lost their mates, 10% bond with other females and 5% form a same-sex ménage a trois.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

This aspect was pursued in detail by Canadian biologist Bruce Bagemihl in his 1999 book Biological Exuberance: Animal Homosexuality and Natural Diversity, in which he described widespread ‘non-procreative sexuality’ in the natural world. Jackdaws are among many species that may form same-sex pairs, he declared.

Their numbers are strong, and growing

The apparent lackadaisical attitude of jackdaws on procreation seems to have had no bearing on population. After significant reduction of British numbers in the 1970s, Corvus monedula is flourishing, with 1.4 million breeding pairs here and some 30 million across Europe. In four sub-species, the bird is found from Scandinavia to North Africa and as far east as central Asia.

Like magpies, they love shiny objects

Our jackdaw was classified in the 18th century by Carl Linnaeus for its habit of picking up bright objects, particularly coins (monedula being from the same Latin stem, moneta, as money).

Indeed, after Adolf Hitler embarked on an art-theft campaign in the 1930s he was derided as ‘the Jackdaw of Linz’, reflecting an appetite for bright objects.

A jackdaw became a saint – at least in a story

The best-known literary jackdaw is found in the Ingoldsby Legends of R. H. Barham, the Jackdaw of Rheims which stole the cardinal’s ring, but returned it and became a local saint.

He long liv’d the pride Of that country side,And at last in the odor of sanctity died; When, as words were too faint His merits to paint,The Conclave determin’d to make him a Saint;And on newly-made Saints and Popes, as you know,It ’s the custom, at Rome, new names to bestow,So they canoniz’d him by the name of Jem Crow!R. H. Barham, the Jackdaw of Rheims

Jackdaws were once shot as vermin

We didn’t always warm to jackdaws. After poor grain harvests, they were proscribed with rooks and crows by Henry VIII in a Vermin Act of 1532, and Elizabeth I ratified this in 1566 with another act ‘for the preservation of grayne’.

Countryside attitudes softened after Victorian game-shooting luminaries Lord Walsingham and Sir Ralph Payne-Gallwey, writing in the 1886 Badminton Library, put them in the second rank of offenders alongside jays, kestrels and hedgehogs as creatures ‘which do some little harm but also some good’.

Jackdaws were ‘as a rule not very mischievous’ and were to be thinned in the woods only to keep their numbers under control. As for the primary raiders – crows, magpies, sparrowhawks, stoats, weasels, polecats, cats and rats – ‘not one bird or beast should be allowed to draw the breath of life on any manor where game preserving is carried on’.

They’re wrongly-blamed for killing small birds

Jackdaw numbers are thinned on some shoots, but, in the wider world they represent little threat. Corvids are blamed en masse for small-bird losses, yet magpies, grey squirrels, cats, changes in land use and habitat destruction are the major culprits.

Indeed, its diet confirms this. Forensic scrutiny by Walter Collinge, described in The Food of Some British Wild Birds of 1913, divided jackdaw crop contents into 42% insects, 29.5% animal matter and 28.5% vegetable matter. Insect and animal constituents spanned earthworms, woodlice, spiders, mice, frogs, snails, slugs, eggs and young birds. Vegetable matter included cereals, potatoes, cherries, berries, walnuts and poultry and game feed. All of this identifies the jackdaw as a useful ally in pest control and only an occasional opportunist feeder on other species.

The ‘chimney bird’ has several other names

The origin of ‘jack’ offers a choice between their brief squawk and the traditional signifier of a small species, with ‘daw’ an English word first recorded in the 15th century, the two halves conjoining in the 16th century. Dialect variants included ka, kae, caddow, caddesse, chauk, college bird, jackerdaw, jacko, ka-wattie, chimney-sweep bird and sea-crow.

They were once thought to be portents of death

These enigmatic birds have a place in folklore, too. A jackdaw on the roof was said to proclaim a new arrival, but might also be a portent of early death. In the Fens, a jackdaw encountered on the way to a wedding was a good omen.

The bird was well known in the Classical world, but its reputation wavered. Ovid declared that the jackdaw brought rain. Aesop used it derisively in his Fables as a stupid bird that starved waiting for figs to ripen: living on hope, which the Fox says 'feeds illusions, not the stomach'. Pliny admired it as a destroyer of grasshopper eggs.

Jackdaws were once believed to have originally been white

The Greeks declared that ‘the swans will sing when the jackdaws are silent’, meaning that the wise will speak after the foolish have shut up. This reflected, to a point, their mythology that all corvids were white until one of their number told Apollo about his wife’s infidelity, at which point he turned the messenger’s feathers black.

A legend among early Christians declared that corvids were indeed white and took black plumage in mourning after the Crucifixion – except magpies, which were too busy pilfering to grieve properly, so turned only partially black.

Why some birds mate for life – and why some play the field (and the trees, ponds and rooftops)

Cooing doves might be synonymous with lasting love, but, when it comes to romance, the bird world isn’t entirely faithful,

Credit: Alamy

The delights of dung: 11 things you never knew about cowpats

It attracts no public regard apart from taking care not to step in it, but it plays a big role

The wren: 8 things you ought to know about Britain's most common bird

It may be diminutive, but the perky-tailed wren has a powerful song and the ancient title of king among birds,

Delights of the daisy: The tiny flower with huge charm that's entranced artists for centuries

We all love a daisy chain, but there’s more to this humble flower than meets the (day’s) eye, discovers Ian

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.