Iridescence: The greatest special effect in Nature

A lustrous play of colour alchemy, natural iridescence can intrigue, camouflage and incite desire. Laura Parker immerses herself in one of Nature’s greatest special effects.

It took 1,000 beetles to make one of the most celebrated dresses of the 1880s. Audiences gasped when Ellen Terry made her entrance as Lady Macbeth, her costume shimmering with the sheeny wings of green jewel beetles. The showstopper caused Oscar Wilde to remark that Shakespeare’s villainess evidently ‘took care to do her shopping in Byzantium’. Society portraitist John Singer Sargent, who loved to paint lustrous fabrics, was also captivated and the actress posed for him, arms uplifted, crown held aloft, in what was to become one of his most arresting works.

The theatrical trick that dazzled them all was iridescence.

'Miss Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth', wearing a dress of green jewel beetles, by John Singer Sargent.One of Nature’s special effects, it occurs when a surface appears to change colour, depending on the angle from which it is viewed. Jewel beetles are some of its glossiest exponents, the many reflective layers of their wing casings producing metallic greens and blues.

These have been used decoratively in Asia for centuries, embroidered into clothing and appliquéd to leather. The ancient Egyptians placed them reverently in burial chambers: crushed to a powder, they decorate a cane in Tutankhamun’s tomb. W. B. Yeats was right to say ‘eternity is in the glitter on the beetle’s wing’.

How iridescence works

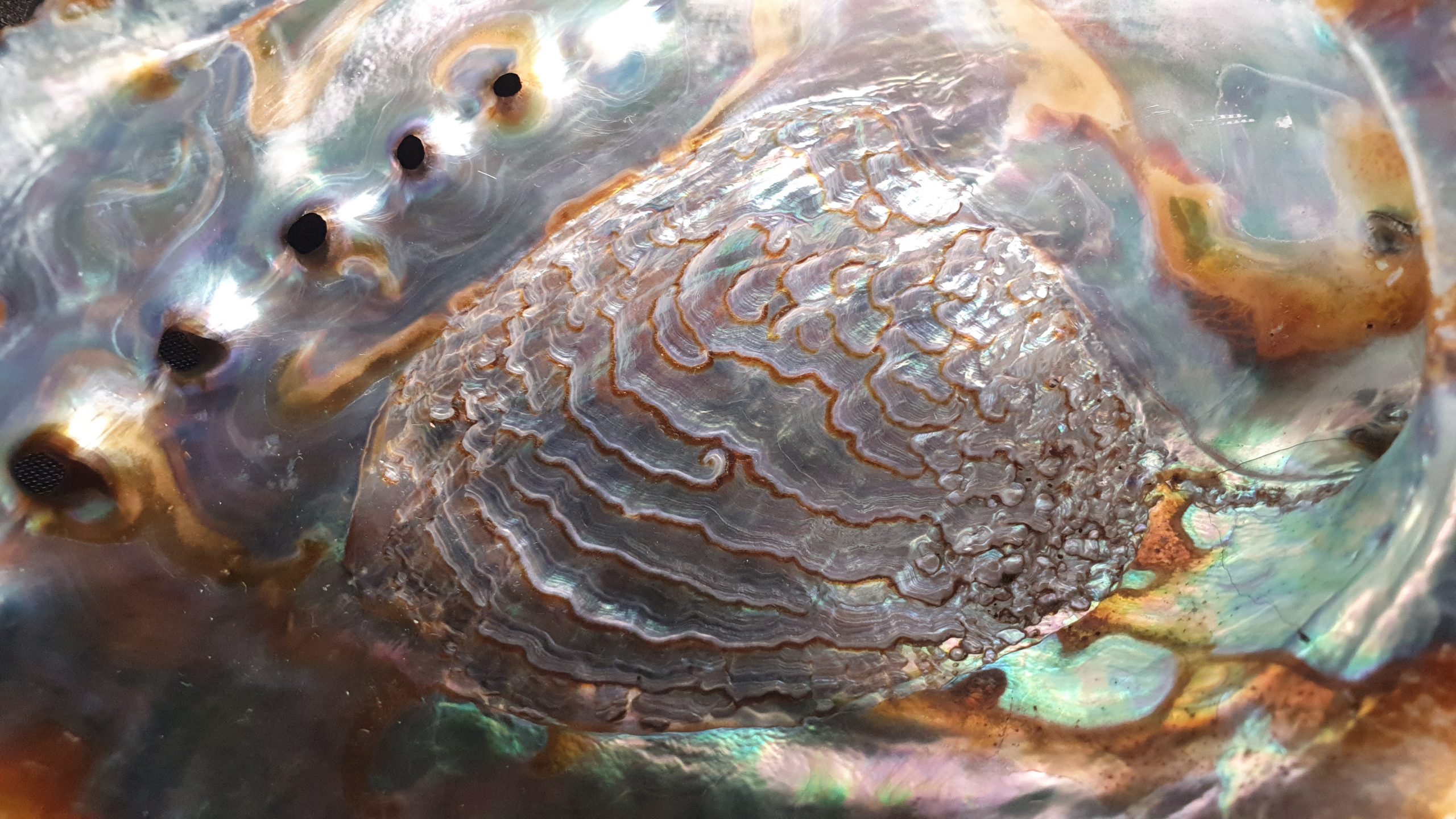

The hallmark of iridescence is its shimmery, colour-shifting effect. The word stems from iris, the Greek for rainbow, with the Latin suffix -escent, meaning resemblance. It is often used interchangeably with nacreous, opalescent, metallic or pearlescent. The colours can vary in hue and intensity, ranging from the dazzling blue of the morpho butterfly, so bright it can be seen by aircraft pilots flying over its native Amazonia, to the subtle creams and ivories of mother-of-pearl. Both effects are produced by the multiple reflections from two or more semi-transparent surfaces.

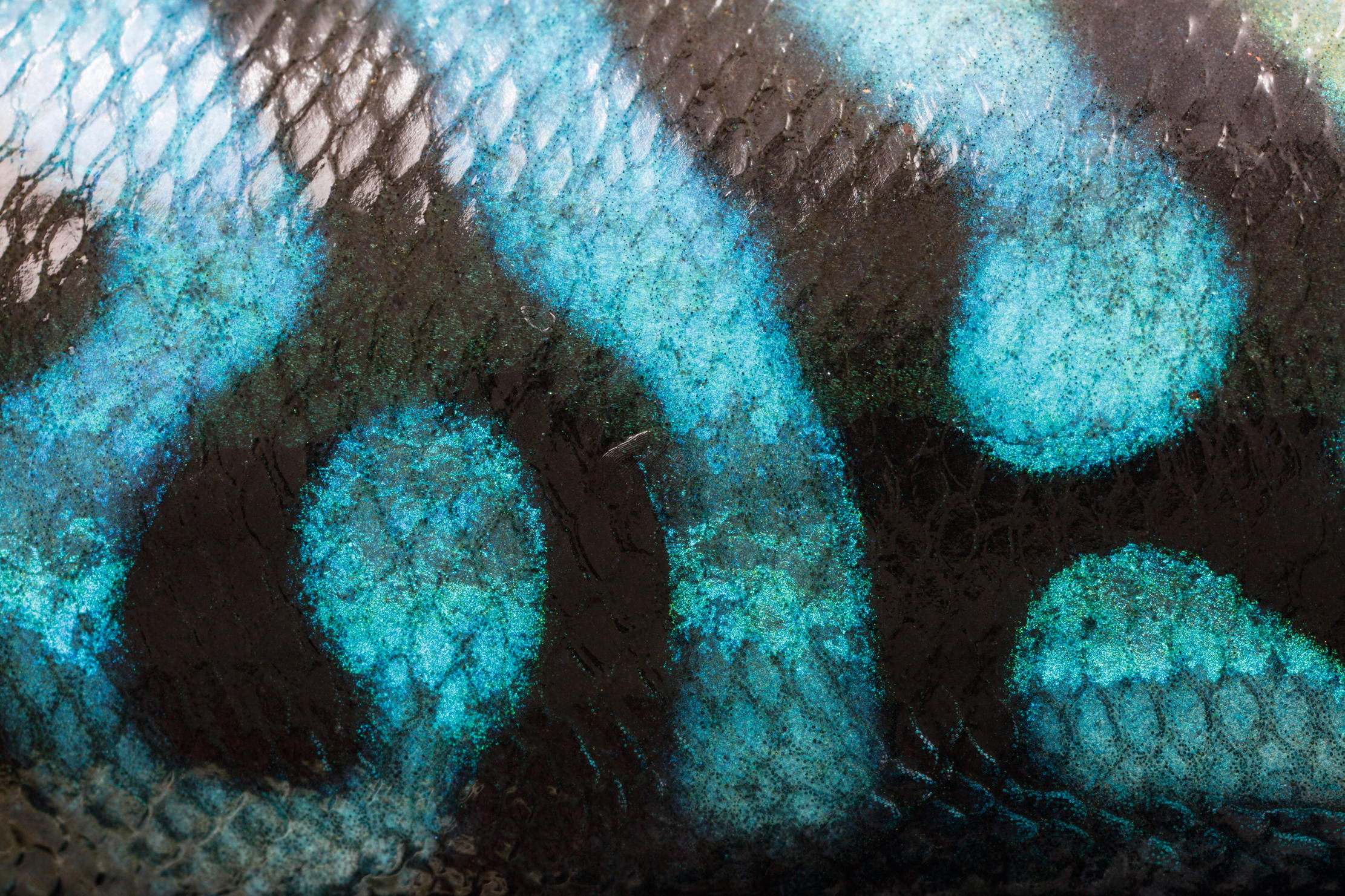

Iridescence is a form of structural colouration: one way we see colours. Rather than coming from pigments, which absorb and reflect particular wavelengths of visible light, the colours are produced by nanostructures on scales, feathers or exoskeletons that refract light at different wavelengths. As iridescent materials don’t absorb light, they resist fading, which is why they survive so well and have even been found in 161-million-year-old dinosaur remains.

Iridescence is found throughout Nature — in birds, molluscs, fish and even plants, as well as insects. It has a vast palette, from the delicate pinks and teals of a soap bubble to the showy turquoise and bronzes of a peacock’s ‘eyes of God’. It appears to have a range of functions, some rather prosaic when compared with how it is prized. An oyster shell’s silky nacre, or mother-of-pearl, is a protection from parasites and irritants, built up of composite layers of calcium carbonate and protein. In birds, iridescence is a signal to attract potential mates or to ward off enemies and claim territory.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

For something so flashy, it is a surprisingly useful disguise. Even the most lurid beetle can remain camouflaged amid shiny leaves in dappled shade. The celadon-coloured underside of the green hairstreak butterfly’s wings blends beautifully with the blaeberries in its heathland habitat. Iridescence also provides further protection by making predators think twice about attacking. Its role as a means of communication among airborne creatures is still being explored.

We have always been intrigued by iridescence. Aristotle wrote about it in his Historia animalium (History of Animals); it was key to Isaac Newton’s discovery that clear light is composed of seven colours; and Darwin mused on its role in a peacock’s display. Our fascination reached its fashionable height in the late 19th century, when Victorians fully embraced the use of materials derived from living creatures. The era saw the adoption of techniques from across the Empire, with fads from fish-scale embroidery to mother-of-pearl buttons. The latter were collected by East End costermongers, who stitched them onto the side-seams of their trousers, leading to the tradition of pearly kings and queens.

Society ladies had worn beetle-bedecked dresses a few decades before the Lady Macbeth example and they took a shine to insect-inspired jewellery, too. In 1885, the Portuguese ambassador presented Foreign Secretary Lord Granville’s wife with a necklace made from 46 iridescent green South American weevils. However, the most eye-catching and outrageously iridescent piece of neckwear, glimmering intensely in newly gaslit interiors, was made from hummingbirds. New Bond Street jeweller Harry Emanuel’s creation was made up of the whole ‘skins’ of seven hummingbirds: four red and three green. He covered their beaks with gold, placed precious gems where their eyes had been and then mounted each bird on to a gold pendant before linking them together. He was so delighted with his hummingbird necklace that he patented the technique and earrings followed.

The hummingbird craze began at the 1851 Great Exhibition and a display of stuffed hummingbirds at London’s Zoological Society that year, artfully arranged in exotic foliage by avian artist and collector John Gould, attracted more than 75,000 visitors. Queen Victoria was among those enamoured, saying it was ‘impossible to imagine anything so lovely as these little hummingbirds, their variety, and extraordinary brilliancy of their colours’.

Unfortunately for these exquisitely tiny birds, the frenzy resulted in mass trapping. Native to the Americas, hummingbirds come in a wonderful array of colours, reflected in their names: sun gem, fairy, woodstar, sapphire, sylph, ruby-throated, calliope. Male birds can self-direct the iridescence on their plumage to attract mates or defend territory, turning muted hues to ruby red or vivid green to cerulean blue. The most vibrant feathers are on their throats, in a patch known as a gorget. The word echoes the name for a knight’s armoured collar and, rather ironically, is still used today to describe crescent-shaped neck jewellery.

By the late 1880s, London had become the centre of a £2 million trade in exotic plumage. One dealer made a single order that included 6,000 bird of paradise feathers, 40,000 hummingbirds and 360,000 feathers from various East Indian species. Hummingbird ‘skins’ were among the most coveted and highly-traded commodities: 400,000 were sold in one week.

Hummingbirds only just survived the slaughter. Numbers recovered from near extinction, but, today, 10% of the 366 species are considered globally threatened and 60% are in decline. The mass collection and killing of birds of all feathers slowed down after the formation of the Society for the Protection of Birds, a merger of two groups of women outraged at the ‘murderous millinery’: Emily Williamson’s Plumage League and Eliza Phillips’s Fin, Fur and Feather Folk. By 1899, the new organisation — which would later add ‘Royal’ to its name and become the RSPB — had 20,000 members and Queen Victoria had decreed that military regiments should no longer wear osprey feathers. Imports were eventually banned by the 1921 Importation of Plumage (Prohibition) Act.

Iridescence in birds is not restricted to exotic species and can be found much closer to home. Watch a city-centre pigeon turn its head and see how its neck colours appear to shift from violet to viridescent and vice versa. The mallard drake in the park has an emerald head and a sapphire patch at the back of its wings, both iridescent.

Lev Parikian, bird enthusiast and author of four Nature books, including the highly praised Taking Flight, enthuses: ‘My favourite is the glimmer on the stock dove’s neck. And even more beautiful is the flash on a teal wing. The magpie, a bird you could easily assume is monochrome, has wonderful blue and purple. Lapwings have a similar vibe — from a distance they can look black and white, but, again, there’s that terrific green/purple sheen when caught at the right angle.’

Yet the spectacular plumage of the kingfisher, our most brightly hued bird, is only semi-iridescent. The spongy nanostructures of its feathers vary in dimension; to be truly iridescent, the layers of material need to be perfectly aligned and repeated periodically.

Eye-catching insects can help us learn to love our declining invertebrate populations as we start to appreciate fully their vital roles as pollinators, food sources and clean-up specialists. Some of the more obviously beautiful ones can be found around rivers and lakes, such as the large emperor dragonfly, with its sky-blue abdomen, and the delicate demoiselle damselfly, which sports a metallic green-bronze body.

Vicki Hird, author of Rebugging the Planet and champion of essential insects, says: ‘In gardens, I enjoy seeing the super-stripy rosemary beetle, a relative newcomer to the UK. From late spring, I seek out gorgeous green nettle weevils in Epping Forest and whirligig beetles in ponds.’

Only one mammal has iridescent fur. The African golden mole has a sheen of blue, violet and copper, thought to have evolved to minimise friction when burrowing. However, many nocturnal animals have a layer of iridescent tissue behind the retina in their eyes. It helps them to see better in the dark and explains the spooky eyeshine when a fox or a cat is caught in torchlight.

Iridescence is both irresistibly attractive and incredibly hard to reproduce. Although the scales of herrings and sardines have been mixed into a paste to coat fake pearls since the 17th century, ‘interference’ paints containing silicate minerals to replicate lustre have only been around since the 1960s.

As so often, we cannot improve on Nature. Biologist Cédric Finet studies the evolution of colours in butterflies with the aim of developing new bio-inspired materials: ‘Artists and engineers are endeavouring to re-create structural colours, but it is in Nature, far from paintbrushes and workbenches, that the most vivid colours come to light.’

We may not forgive Emanuel his hummingbird necklace, so repellent today, but we can understand his impulse to harness a colour trick so brilliant it outlasts the death of the creature. The wings on Dame Ellen’s dress are as bright now as the day she wore them.

Laura Parker is a countryside writer who contributes to the Scottish Field, the Dundee Courier and Little Toller’s nature journal The Clearing. She lives in the Cotswolds and keeps a small flock of Shetland sheep. You can follow her on X and Instagram: @laura_parkle.