In Focus: Tarka the Otter, Henry Williamson's great masterpiece of Nature writing

Jack Watkins tells the tale of what might have been a simple tale of nature, but which became a phenomenon both on page and on screen.

In the 21st century, the cameraman, both still and moving, has taken the place of the writer as the most trusted observer of wildlife. However, in the days before sophisticated photography and documentary film-making were possible, the pen was still king, which is why, on first publication in 1927, Tarka the Otter was immediately hailed as a masterpiece.

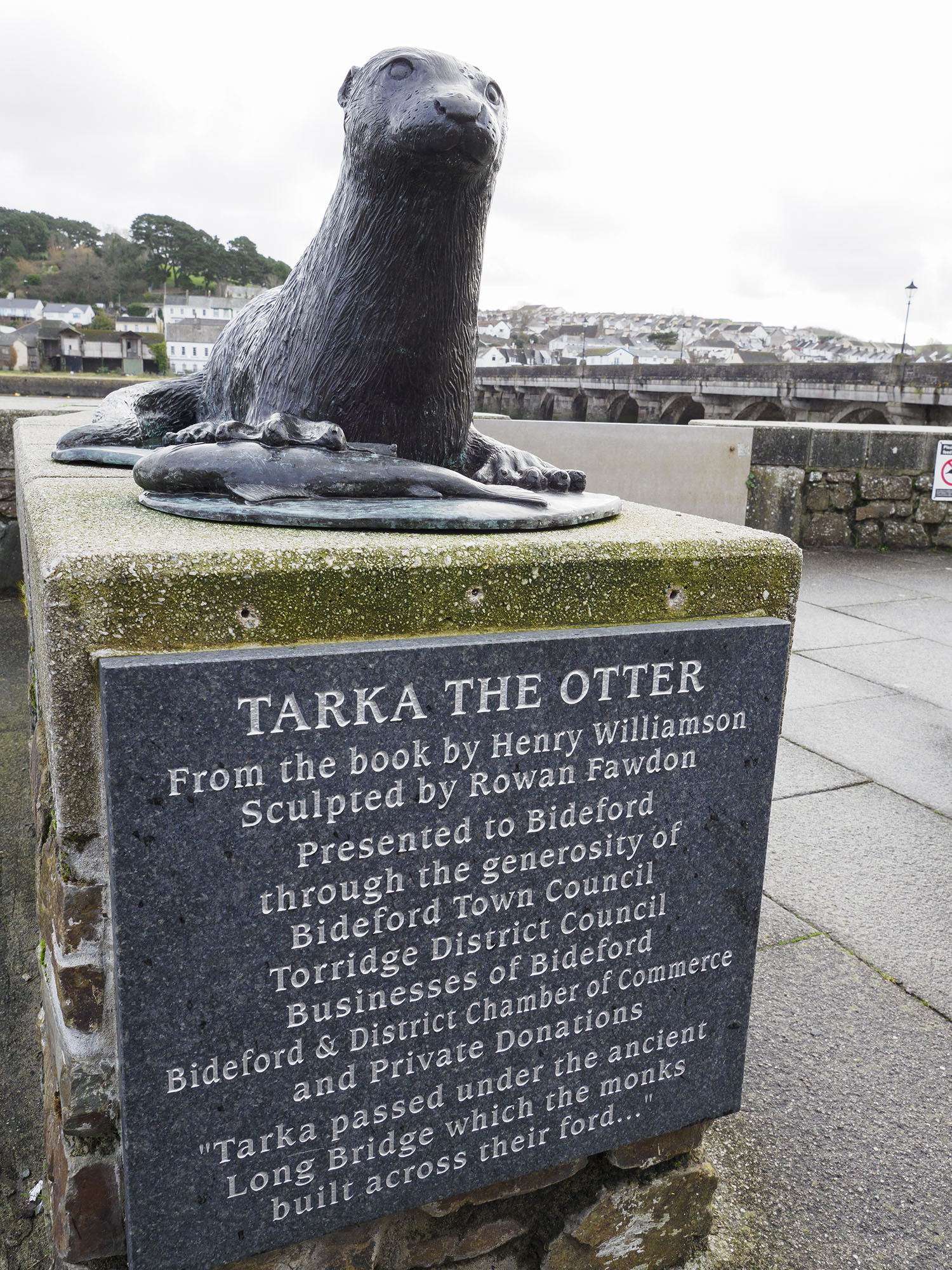

A minutely observed account of the life of an otter in the Devon countryside of the Two Rivers (the Torridge and the Taw), it was ‘a true story’, or at least ‘as true as a man’s account of the life of a wild animal can be,’ wrote Eleanor Graham in an introduction to a later reprint. It won its author the Hawthornden Prize for Literature the following year and even drew praise from a West Country literary giant, the ailing Thomas Hardy, who died in 1928.

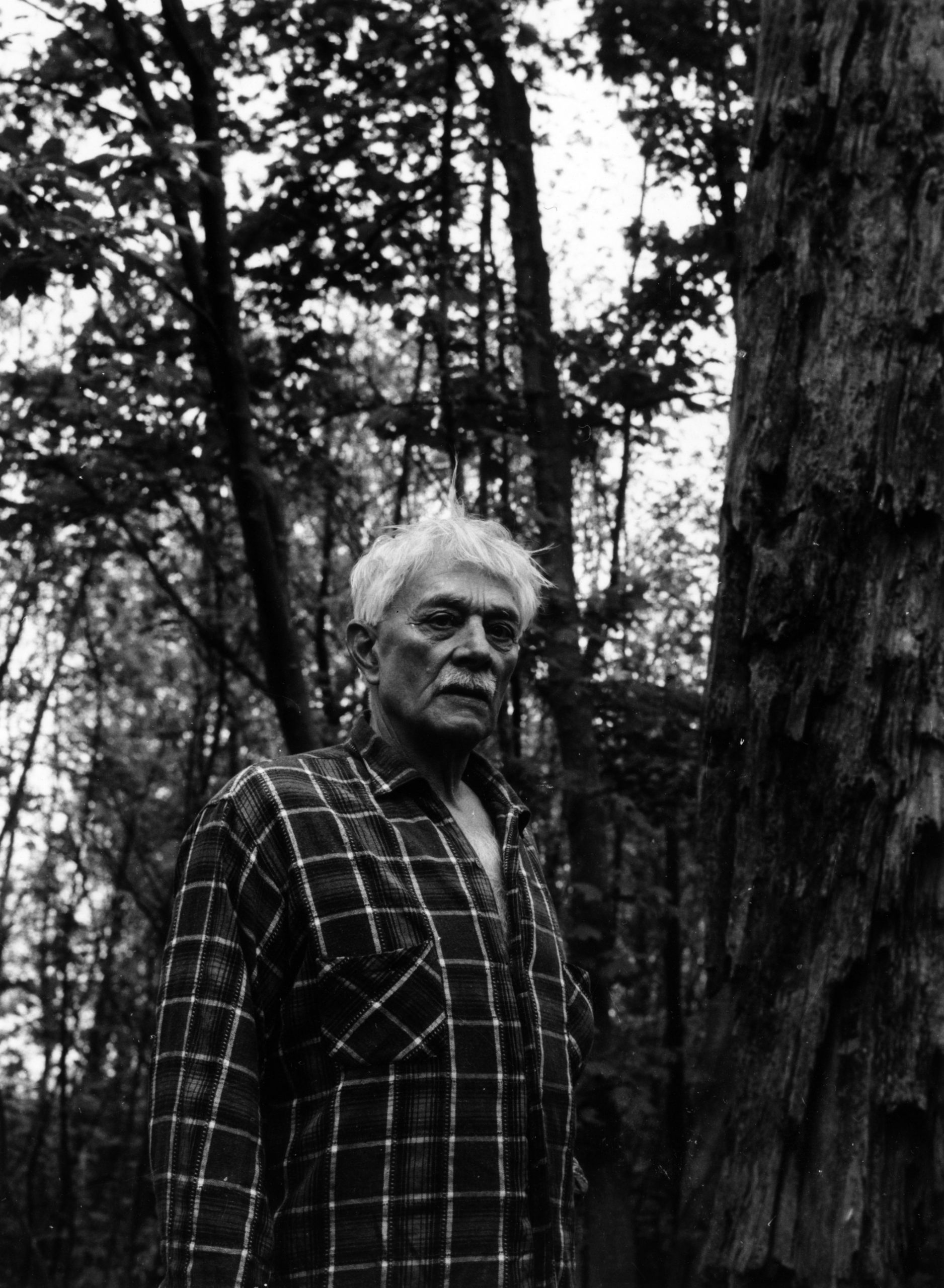

Yet Henry Williamson had only seen two otters in his life before he took up residence in north Devon in 1921. The author, mentally scarred by his experiences in the First World War trenches and having spent several unsettled years in London, had rented Skirr Cottage in the village of Georgeham, where he had enjoyed an idyllic holiday in 1914 shortly before the outbreak of hostilities. His intention was to make a living from writing about the countryside.

The idea for the story of Tarka’s ‘joyful water-life and death’ stemmed from an event shortly after arrival at Georgeham, when Williamson was approached by a local to help rescue some orphaned otter cubs whose mother had been shot by a farmer. Williamson brought one of the cubs back to the cottage, where his cat, at first reluctantly, acted as foster mother.

Although the otter learnt to respond to Williamson’s call and joined him on his evening walks, on one occasion the writer discovered it caught in a rabbit snare, hissing with pain. Although he managed to release it, the otter broke free of his grasp and bolted. Williamson searched the countryside for several weeks, but never saw it again.

“I knew the prose was straight, keen and true – facts, you know. It is all here in Devon, if you just happen to see and hear or smell it”— Henry Williamson

At about the same time, Williamson read a book by the Cornish naturalist J. C. Tregarthen, The Life Story of an Otter (1909), which provided further inspiration. As well as walking extensively, teaching himself to observe the land from an otter’s eye level, he went out with the Cheriton Otterhounds. From this experience came the descriptions of the ‘killer’ hound, Deadlock, the ‘master of all’, the sense of a life lived in the shadow of his recurring menace and the book’s tense and awful, but non-judgmental climax. For the accurate descriptions of otters moving though water, Williamson relied upon notes made during zoo visits.

The critics on Tarka the Otter

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

“Tarka, to anyone who’s tried to write, is a technical delight, all the more perfect for being imperfect here and there.” — T. E. Lawrence“I consider it to be over-written...The author has searched too often and too long for the utterly right word.” — Arnold Bennett“Mr Williamson is the finest living interpreter of the drama of wildlife.” — John Galsworthy“A holy book, a soul-book, written with the life blood of an unusual poet.” — Ted Hughes

Although there are anthropomorphic touches, such as the allocating of names to wild creatures — Old Nog the heron, Halcyon the kingfisher and, of course, Tarka himself, the name meaning Little Water Wanderer — the absence of sentimentality is striking. Even so, the descriptions are atmospheric and were lent further power when Charles T. Tunnicliffewas brought in to provide illustrations for a later version in 1932.

The book’s opening is surely among the best in fictional Nature writing. ‘Twilight over meadow and water, the eve-star shining above the hill, and Old Nog the heron crying kra-a-ark! as his slow dark wings carried him down to the estuary’ is so visual and true that it says more than hours of wildlife film. Williamson created literary landscape portraits, as well as managing to convey how a wild animal shuts out all that is unnecessary to its prime object, that of survival. He was so keen to be exact that he claimed to have rewritten the manuscript 17 times. He was rewarded by the respect not only of literary types, but of naturalists and others, whether at work or play, who spent long hours in the countryside.

The life and times of Henry Williamson

Henry Williamson (1895–1977) is remembered today for Tarka the Otter above all else. This is unsurprising, not merely for the moving account of Tarka’s life, but also for the meticulous descriptions, realised from hours of exploring the moors and riverscapes, listening as well as watching. Book sales have been estimated at four million worldwide.

Tarka is also remembered in the Tarka Trail, established in 1987 as a signposted tourist route, including footpaths and cycleways, through the Devon countryside covered by the otter (www.tarkatrail.org.uk). For an easier ride, The Tarka Line, running between Barnstaple and Exeter, passes through several of the story’s landmark locations (www.greatscenicrailways.co.uk).

Williamson became a controversial figure for his support for Oswald Mosley’s Fascists in the 1930s and his pre-war approval of Hitler. Although he later condemned the Fuhrer as Lucifer, the Prince of Darkness, it inevitably damaged his reputation. Williamson’s experiences in the First World War certainly left a permanent scar and some have even seen Tarka as an allegory of war. Yet he was an outstanding writer and his immense output describing Nature and the countryside includes Salar the Salmon (1935) and The Story of a Norfolk Farm (1941).

Where, when and how to spot an otter in the wild

Otters can live in most places where there is a rocky shoreline and nearby freshwater, but these tips collated by

Credit: Richard Cannon/Country Life Picture Library

Rudi the otter: 'we had to convince Parliament to focus on clean water and the easiest way to do that was with a baby otter'

Affectionate and loving he may be, but small-clawed otter Rudi has a purpose.

Badgers, weasels, otters, stoats and more: A guide to Britain's mustelids

Lithe, opportunistic and with a predilection for poultry, these elusive, often pocket-sized predators have long raised a stink for farmers

Somerset born, Sussex raised, with a view of the South Downs from his bedroom window, Jack's first freelance article was on the ailing West Pier for The Telegraph. It's been downhill ever since. Never seen without the Racing Post (print version, thank you), he's written for The Independent and The Guardian, as well as for the farming press. He's also your man if you need a line on Bill Haley, vintage rock and soul, ghosts or Lost London.

-

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbinding

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbindingAn exhibition on the legendary bookbinder Roger Powell reveals not only his great skill, but serves to reconnect us with the joy, power and importance of real craftsmanship.

By Hussein Kesvani

-

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary Britain

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary BritainCourtesy of our ‘special relationship’ with the US, Spam was a culinary phenomenon, says Mary Greene. So much so that in 1944, London’s Simpson’s, renowned for its roast beef, was offering creamed Spam casserole instead.

By Country Life