In Focus: How Roald Dahl's love of the countryside shaped his life's work

The countryside filled the Matilda author Roald Dahl with joy and proved a constant source of inspiration, as Matthew Dennison reveals in a new biography of the prolific storyteller.

Roald Dahl’s attachment to the country ran deep. In the year he died, he claimed that he had ‘never lived in a town or city in my life and I would hate to do so’. Like Danny’s father in Danny the Champion of the World, he regarded himself as ‘a true countryman’: ‘the fields, the streams, the woods and all the creatures who lived in these places were a part of his life’. Albeit a partially misleading statement, his denial of town-dwelling and assertion of his love of the country accurately reflected his feelings.

In fact, Dahl, who was born in 1916, spent much of his childhood in the north of Cardiff. His father died when he was three, prompting his mother to sell their large Victorian farmhouse outside the city, Ty Mynydd, which had a working piggery, woodland, pasture and, as Dahl remembered rosily, ‘haymaking, hay wagons and horses’ and, at harvest time, fields of corn stooks through which he and his sisters wandered at will. By contrast, their new home, Cumberland Lodge in Llandaff, was a four-square red-brick suburban villa: tall hedges enclosed its generous gardens of cricket nets and doily-patterned rosebeds.

Happily, there were trees to climb. At the top of a mighty horse chestnut, Dahl wrote his secret diary: ‘It was lovely being high up there in that conker tree, all alone with the pale young leaves coming out everywhere around me,’ he recalled later. Most of all, he relished its springtime ‘cave of green leaves’ and his sensation, perched among the flowering branches, of being ‘surrounded by those wonderful white candles’.

For the remainder of his life, a sense of wonder coloured Dahl’s engagement with Nature and the country. On the table in the writing hut in which he worked seven days a week, fortified by a flask of coffee and a supply of his preferred Dixon Ticonderoga 1388–2 5/10 (medium) yellow pencils, specially ordered from New York, clustered a collection of his favourite objects, including a carving of a grasshopper and a cedar tree cone. The country provided the setting for much of his writing. ‘If you live in the country, your work is bound to be influenced by it,’ he commented in the early 1950s.

Frequently, the country moved him to lyrical admiration. Matilda, for example, first visits Miss Honey’s cottage on a golden autumn afternoon when ‘there were blackberries and splashes of old man’s beard in the hedges, and the hawthorn berries were ripening scarlet’. In The Magic Finger, even the villainous Mr Gregg is moved by the sight of the night sky: ‘He stopped and looked up. The night was very still. There was a thin yellow moon over the trees on the hill, and the sky was filled with stars.’ Dahl’s first story, The Gremlins, begins ‘in early autumn, when the chestnuts [are] ripening and the apples beginning to drop off the trees’.

More than 30 years after his death in 1990, Dahl’s reputation is understandably tarnished by distaste for his antisemitism. Yet, for me, he remains a master storyteller and, as I discovered working on his biography, a man for whom the simple, good things of life provided enduring pleasure, as well as solace at moments of tribulation or suffering. In 1954, he and his film-star wife, Patricia Neal, bought a small, square, white-painted farmhouse, on a gentle incline that traced the path of an ancient drove road, a short walk from the village high street of Great Missenden in Buckinghamshire. Around it, gardens and green slopes extended over five acres.

All was desuetude and neglect, but, beyond a clutch of outbuildings of brick and dun-coloured rubble, an old orchard lay full of apple and pear trees — this was a boon for Dahl, for whom it was ‘a most marvellous thing to be able to go out and help yourself to your own apples whenever you feel like it’. The Dahls arrived in the middle of May, when ‘the hawthorn was exploding white and pink and red along the hedges and the primroses were growing underneath in little clumps, and it was beautiful’. Dahl remained there for the rest of his life. He renamed the house Gipsy House.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

A beech tree at the top of the orchard became the setting for Fantastic Mr Fox; staring at a cherry tree in the same grassy enclosure, he pondered what would happen if the cherries were to grow and grow and not stop growing, then he asked the same question of apples and pears, and then he thought of a peach. In 1959, he published a story in The New Yorker called The Champion of the World. When, in 1975, he revisited the tale, turning it into a full-length novel for children, Dahl’s lilting evocation of idealised, romantic, rakish country life drew inspiration from the garden of Gipsy House, and the brightly painted gipsy caravan, bought from his brother-in-law, in which all his children played.

Gipsy House provided the setting — as well as the stimulus — for Dahl’s work. His writing hut in the garden, approached along a neat path, was a private sanctum where, with curtains drawn against distractions, he immersed himself in what he called his ‘dotty world of fantasy’. However, Gipsy House was much more than a writer’s quiet retreat. A setting for the rambunctious, close-knit family life Dahl valued, it was also where he grew vegetables, amassed an extensive collection of hothouse orchids and watched birds.

In the summer of 1960, with building work ongoing on the little house, he recorded delightedly the spectacle that greeted him each morning on his short walk from the house to his writing hut: new plantings of roses; cattle in the fields beyond and ducks on the grass; bright shoots of young spinach in the vegetable beds; and, in branches in the orchard, blue and green budgerigars that roosted in a new octagonal birdhouse.

Dahl was a man of contradictions, fascinated by the lives of the rich, but equally drawn to the raffish world of local greyhound racing. At Gipsy House, he grew enormous onions to enter in local shows. In a corner of the Home Counties, this Welsh-born son of wealthy Norwegian parents restored the vanished Eden of his early childhood, a painstakingly tamed idyll that recalled his hazy memories of the farmhouse outside Cardiff in the closing years of the First World War.

Dahl’s view of country life was not a sportsman’s. As a schoolboy at Repton, in Derbyshire, he had occasionally followed the Burton Beagles, but he grew to dislike fieldsports and his antipathy to shooting is key to the plots of The Magic Finger and Danny the Champion of the World. The writer kept a series of ‘ideas books’, in which he noted thoughts and reactions alongside kernels of new stories. ‘I have yet to be convinced that a man has the right to kill the anopheles mosquito merely because his strength and brains enable him to do so, or to kill any other animal, reptile or insect,’ he wrote in one. ‘Obviously, it is murder.’ It was a conviction that hardened over time.

An elderly Dahl recorded his thoughts about the months of the year, published posthumously as The Roald Dahl Diary and, subsequently, My Year. It was a hymn to Nature’s bounty written with the storyteller’s instinct he had sharpened over a lifetime. Musing on his favourite month, September, Dahl told his readers, ‘the colour of the entire landscape is slowly changing from green to gold’. The delighted anticipation of Dahl the countryman is palpable.

Matthew Dennison’s biography of Roald Dahl, ‘Teller of the Unexpected: The Life of Roald Dahl’, was published in August (Head of Zeus, £20)

How four of the greatest writers in history thrived in their garden sheds

Over the years many writers have found a garden shed to be a perfect place to lock themselves away from

My Favourite Painting: Quentin Blake

Quentin Blake chooses his favourite painting for Country Life.

Quentin Blake: 'Even in the age of the iPad and the smart phone, books offer things that they cannot'

Sir Quentin Blake reveals the inspiration behind his new exhibition, ‘Anthology of Readers’, in which he affectionately caricatures the bookish

Credit: Alamy / Sir John Tenniel

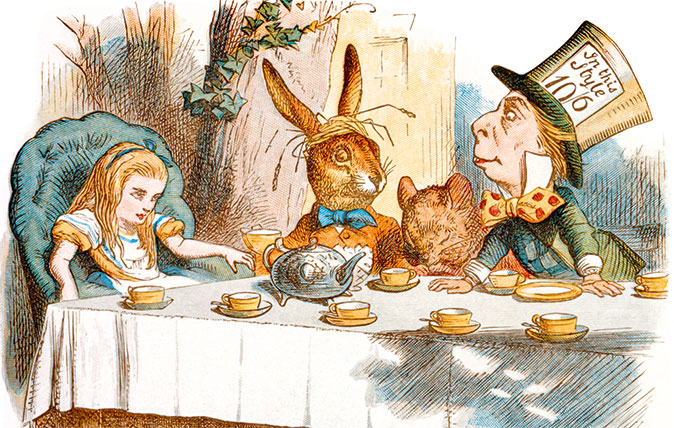

10 of the greatest children's book illustrators, from EH Shepard to Quentin Blake

Matthew Dennison pays tribute to artists who painted our collective childhoods.