HRH The Prince of Wales: Why we must save our trees

In his birthday message to the countryside, His Royal Highness The Prince of Wales urges us all to work together to safeguard our emblematic British tree species from pests and lethal diseases.

One of the many things I love about the British countryside is its enduring timelessness which creates a tangible link with our past, while continuing to provide contemporary livelihoods, food production, a home for wildlife and abundant scope for recreation and relaxation among natural beauty. Some of those things have an economic value, others are important in different ways. But they all matter deeply to me and, I know, to a great many other people too.

Those of us who care about the countryside know that it is more fragile than it may appear. In a world of heavy machinery, intensive agriculture, blanket forestry and insensitive land drainage and development – compounded, of course, by the impacts of accelerating climate change – stringent safeguards and constant vigilance are necessary to ensure we maintain and improve the best of our natural inheritance.

A great deal of attention has rightly been given to the plight of our endangered wildlife and wild flowers, and there have been some encouraging successes, such as the recovery of the cirl bunting and the reintroduction of the large blue butterfly. On a personal note, I am proud of having encouraged the creation, so far, of more than ninety Coronation Meadows, each full of local, native wild flowers, and am immensely grateful to Plantlife and the many landowners now participating.

At the same time, and despite strenuous efforts to turn the tide, our native red squirrels remain under threat as do many species of ground-nesting birds, but most of all the curlew, whose population has suffered an alarmingly severe and rapid decline partly as a result of increasing predation. Their haunting, evocative cries, which led Ted Hughes to write that ‘Curlews in April, hang their harps over the misty valleys… wet-footed god of the horizons’, are just a memory in many places where they used to breed in their hundreds.

Another distant memory, from a time before the 1970s, is of hedgerows punctuated by billowing English elms, providing height in the landscape, shade for livestock and a haven for wildlife. More than 25 million are estimated to have been lost to Dutch Elm Disease, spread by the elm beetle that carries a deadly fungus. A few areas have escaped the worst of the destruction, but today the elm survives mainly as a suckering hedgerow plant, cut down by the disease as soon as it gets above head height.

I have always been mortified by the loss of mature elm trees from almost every part of the countryside I knew and loved as a child, so I had high hopes for an American variety that appeared to be resistant to the disease. I planted an avenue of them at Highgrove and then watched, miserably, as many of them succumbed just like the native variety.

Losing almost every sizeable English elm from our countryside – particularly in Gloucestershire and Somerset – was such a profound change that I suspect every Country Life reader will have heard of Dutch Elm Disease. The wider problem is that a great many more pests and diseases are now seriously threatening the health of all our native trees, yet public awareness of this situation seems to be frighteningly low.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

These new threats are not just to the appearance of the countryside, important though that is. Trees have an important role in many aspects of our lives, contributing to our wellbeing and providing us with a wide range of essential environmental services, as well as timber, fruit and fuel.

It is easy to appreciate that tree roots, by penetrating deeply into the soil and binding with it, provide stability and prevent soil erosion. But that same process also creates a more open soil structure, rich in organic material, which can absorb more water, thereby improving drainage. Following the devastating floods of recent years there is a lot of interest in any measures which can slow the rate at which water runs off the land. There are no simple answers, but it certainly appears that sensitive tree planting has a role to play, both in the uplands and in the sustainable drainage schemes which are increasingly being developed in urban areas.

As part of one of Nature’s many cyclical processes, tree roots also bring nutrients needed by other species to the surface. The roots absorb what the tree needs to grow and make leaves, seeds and fruit, and when they fall and decay the nutrients become available on the ground. This is one of the reasons why our woods are so rich in wildlife.

At a larger scale, trees and other plants are the lungs of our planet, soaking up carbon dioxide from the air and helping to combat – in a losing battle if we do not tackle it with appropriate urgency – the climate change that threatens humanity with increasing, catastrophic consequences. Trees also filter pollutants from the air and absorb water from the ground into their leaves, which starts the all-important water cycle that provides the rain needed by all terrestrial life, including ourselves.

Trees continue to contribute to our wellbeing long after they have been felled, as anyone reading this while surrounded by wooden furniture or under a timber-framed roof will be quick to appreciate, and particularly if they are being warmed by a log fire or wood-burning stove. Adding mushroom soup or roast chestnuts to the scene would be a bonus, for the production of each of these items will have provided someone with a livelihood and avoided the use of man-made materials such as plastic or other derivatives of fossil fuels.

Against that background, the benefits of healthy trees, woodlands and forests are clear, which is why we should all be seriously alarmed by the recent rapid increase in tree pests and diseases in this country. I am told there appears to have been a step change in the early Nineties, with the average number of new pest species becoming established increasing to nine per year. Not all of these have caused serious problems, but the threat is very real. The causes of this situation are not clear, but are likely to include the ease and speed of transport, with the use of controlled environments; the response of the trade to consumer demand for new plants; and climate change, which makes the United Kingdom ever more suitable for warmth-loving organisms.

My personal experience extends beyond the Highgrove elms. A fungal disease known as Phytophthora ramorum has affected mature larch trees in the Duchy of Cornwall woodlands. Ash Dieback has affected trees at Highgrove and at a Welsh property owned by the Duchy. The term ‘dieback’ is something of an understatement as there are no remedies and each is effectively fatal, not least because infected trees must be felled promptly to slow the spread of the disease. I am far from being the only one who has watched trees they have planted and nurtured succumbing in this way. Trees that were carefully chosen for a particular site, or that have grown there naturally for thousands of years, have to be felled and burnt, and cannot be replaced with the same species. Already, some of this country’s most historic parkland settings with ancient oak trees that have stood for 800 years, are threatened with devastation. It is a horrible experience for anyone who loves trees, or depends on them for their livelihood, and one that is becoming more common by the day.

This is a topic in which I have been taking a wider interest over the past few years, including convening meetings of scientists, foresters, amenity groups and regulators, all of whom are as alarmed as I am by what is going on and the implications for the landscape, environment and a wide range of economically important activities.

At these meetings I have heard about the wide range of exotic pests and diseases now being encountered and the efforts being made to prevent and manage outbreaks. To me, the most telling experience comes from that great British institution, the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, of which I am Patron. Their scientists not only have an extraordinarily valuable collection of plants to protect, they also have the expertise and vigilance to detect the first sign of new problems.

The staff at Kew are currently watching carefully for any sign of a wide range of potential pests, including the Asian Longhorn Beetle, currently confined to one site in Kent, and the Emerald Ash Borer, which is not known to be in this country but presents a major threat to add to the dieback from which many of our unfortunate ash trees are already suffering.

One very serious pest is already established at Kew, as well as at Hampton Court, Hampstead Heath, Greenwich Park and many other locations across at least 25 London boroughs and parts of Surrey. The Oak Processionary Moth is described as ‘an aggressive, pernicious insect pest with serious consequences for human and plant health’. The moths instinctively target the tallest, bushiest and healthiest looking trees to lay their eggs. These then hatch into nests of caterpillars which eat the oak leaves, weakening the trees and potentially killing them over the course of several years. As if this were not bad enough, the caterpillars are covered in long hairs that are easily shed and cause unpleasant, itchy rashes on human skin.

Female Oak Processionary Moths can fly up to three miles to lay their eggs so it is no surprise that their impacts are spreading. Chemical spraying and removing nests has slowed the spread to around one mile per year, but new outbreaks are being reported all the time and it seems unlikely that total containment is possible.

Tragically, this is not the only major threat to the oak trees which grace so much of our countryside. A few years ago a serious disorder of oaks, known as Acute Oak Decline, was detected and found to be spreading naturally from tree to tree. Not all the trees affected die, but some do and many more are weakened. The problem was first detected in the East of England, but seems to be spreading North and West. A lot of research has been conducted into the causes, supported by the fund-raising efforts of many valiant people, including the late Peter Goodwin of Woodland Heritage.

Further research – and, of course, funding – is urgently needed, but Acute Oak Decline appears to be caused by a complex association of native organisms, including a beetle and a fungus. However, all of the other pests and diseases I have mentioned, and a great many more, have been introduced to this country. The fungi that cause Dutch Elm Disease, Phytophthora ramorum and Ash Dieback were all probably imported on infected plant materials. The Asian Longhorn Beetle arrived in poorly treated wood packaging material from Asia and the Oak Processionary Moth is believed to have arrived as eggs on imported trees from Southern Europe.

Imports of live plants, bulbs and cut flowers into this country have more than doubled in the past 25 years, to around 350,000 tonnes, with a value of £1.4 billion. Last year, surveillance at points of entry identified more than 320 pest species, of which 6% had not previously been recorded. But we cannot rely on these border controls alone. Garden and landscape designers, and indeed anyone specifying plants for importation, should understand the threats and be asking searching questions about plant health and biosecurity, including the urgent necessity for quarantine periods.

These threats to our trees, woodlands and forests are extremely serious and far-reaching. Those of us who value their role in the countryside need to do three things. We must highlight the nature and scale of the threat, encourage more scientific research and, above all, ensure that good practice is implemented. These are not, if I may say so, tasks for other people. Everyone has a part to play, starting with raising awareness of how much is at stake; and with concerted action I am sure we can work together to safeguard our iconic National species for the enjoyment of future generations.

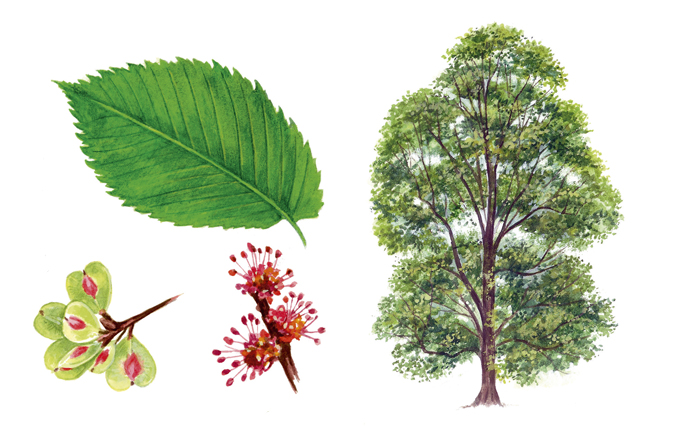

A simple guide to identifying British trees

Simon Lester goes out on a limb to identify species and stop us barking up the wrong tree.

Credit: John Paul Photography / Courtesy of Clarence House

HRH The Prince of Wales: Why we must save the countryside's soul

In his regular birthday message to the countryside, His Royal Highness The Prince of Wales stresses the need for balance

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.