How to keep ducks: What to buy, how to keep them, and nine varieties to get you started

Ornamental waterfowl are an endlessly cheering and fascinating addition to any stretch of water, but they can make a mess. Vicky Liddell asks experienced keepers for their advice. Illustrations by Fiona Osbaldstone for Country Life.

Please note that at the time of writing (November 2022) the UK is currently experiencing the worst outbreak of avian influenza on record and keepers must maintain high standards of biosecurity. Captive wildfowl and waterfowl should be kept in a fully netted area. All feeding and watering should take place under cover or in some form of structure designed to exclude wild birds. To find a local breeder and to learn more about the keeping of both wild and domestic fowl, visit www.waterfowl.org.uk

Anyone fortunate enough to own a large pond or lake will have considered acquiring some web- footed residents. They fondly imagine the gentle call of female birds, the iridescent sheen of the drakes in winter and the enchanting bustling and waggling as the birds go about their daily business.

What they rarely foresee is the time they will spend staring out of the window at the comical love lives of their birds — or how the garden will never be quite the same again.

What are ornamental waterfowl?

Ornamental waterfowl can be divided into four groups: the surface feeders or ‘dabbling’ ducks, which feed on or near the surface; ‘diving’ ducks, which obtain most of their food by diving; sea ducks, which include the eider, the UK’s heaviest duck; and sawbills, a group distinguished by the structure of their bills.

What are the best ducks for beginners to keep?

Surface feeders are generally considered the best for novices to keep; they include the gadwall, pintail, teal, shoveler, wigeon and the exotic mandarin. Diving ducks, such as the scaup, pochard and tufted duck, need more specialised care and a water depth of at least 2ft. Geese and swans may be considered for a larger stretch of water and, of course, in some places they will congregate naturally.

Is it easy to keep ducks?

Waterfowl are, in many ways, easier to keep than chickens. They’re more resilient to extreme weather conditions, so often continue to lay throughout the winter, even if the eggs can be hard to locate.

For new keepers, the best advice comes from the late Lt-Col A. A. Johnson, author of Ornamental Waterfowl (1957), who wrote: ‘Always talk to your birds using the same tone of voice, never hurry and never appear among them in some striking new garment.’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Bear in mind that they can be noisy. Most females will make some sort of quacking sound and there are many other noises, too, but none are as strident as a cockerel. Teal and wigeon whistle, gadwalls grunt and the male eider’s moaning call has been compared to the sound made by the late Frankie Howerd on hearing some juicy gossip.

Waterfowl don’t perch like chickens, so don’t require architectural gems, such the notorious duck house of the 2009 MP expenses scandal, but nest sites should be provided for the breeding season. The main requirement is a fox-proof fence. ‘A determined fox will visit every day until you make a mistake and leave a door open,’ observes author Francine Raymond, a long-term poultry keeper.

Waterfowl are often praised as slug eaters and lawnmowers, but the trample factor should be considered, too. ‘This is more likely to happen when too many birds are kept in too small a space,’ explains Morag Jones, editor of Waterfowl magazine. ‘It is better to have several individuals of a smaller number of species. Three pairs of each species allows a choice of mates and better welfare.’

What sort of pond do you need to keep ducks?

The ideal pond is one of varying depth, well planted with vegetation, trees and shrubs in a sunny, sheltered spot where birds can sun themselves on a bank. Submerged plants will encourage invertebrates for diving ducks and will serve as oxygenators, improving water quality.

An island can offer a safe nesting and resting spot, but never underestimate vermin. ‘Rats are good swimmers and nothing will stop a vixen if she has cubs to feed,’ warns Mrs Jones. Waterfowl will also need, as well as plenty of grass and clean water, a pellet supplement and a twice-yearly worming medication.

Keeping ducks and waterfowl can be addictive

Stephen Breith and Helen Evans of River Cottage Waterfowl keep and breed a varied selection of ornamental waterfowl from all around the world on a beautiful landscaped site next to the River Cam near Cambridge. ‘It started out as a 35-acre wildlife spot for frogs, newts and water plants, but the otters came and pinched all the fish, so we decided to start a waterfowl collection,’ Mr Breith explains. The population has grown annually and now numbers about 1,000, with shelducks, shovellers, wigeon, pochards and pintails, plus various black swans that coexist happily with a variety of fish.

There’s a similar tale to tell at Busbridge Lakes near Godalming, Surrey, where the quacking and honking of about 800 waterfowl from more than 120 species can be heard from miles away. They waddle around the 40 acres of the Grade II-listed heritage gardens, and glide on the three lakes that surround the old coach house of the Douetil family’s Busbridge Hall.

‘I was given my first pair of ducks in 1967,’ recalls Fleur Douetil. ‘Unfortunately, they flew away, but they made us realise how lovely they looked on the lakes. We purchased our first pair of Carolina wood ducks, put up a fox-proof fence and the collection grew from there.’

When should you buy ducks, and how many should you get?

Stephen Breith suggests establishing a pond in October or November, when there are more birds available. He recommends teal as a good species to start with, as there is a wide selection to choose from, but advises: ‘Hasten slowly, don’t buy a van load. Some species are tamer than others, but they will gradually accept their owners as part of their flock and there are always some particularly inquisitive characters. Hawaiian geese are especially friendly and will come inside the house if invited.’

With many waterfowl species now on the endangered list, Fleur Douetil has been breeding vulnerable species, such as the red-breasted merganser, which needs a big lake and plenty of fish. The birds are kept in areas that have been designed to mirror their natural environment and she tries to parent-rear wherever possible. ‘I feel it is important for future generations to be able to see and enjoy them.’

10 best types of duck to keep

Wigeon (Anas penelope)

A medium-sized duck, wigeon are exclusively vegetarian and make excellent lawnmowers. The drake makes a far-reaching whistle that is answered by the female with a growling quack.

Northern shoveler (Spatula clypeata)

This aptly named, surface-feeding duck has a huge shovel-shaped beak, which it swipes from side to side to filter planktonic crustaceans out of the water. The birds do well in a collection and become quite tame, although the ducklings can be delicate. Its courtship ceremony involves a strange, synchronised-swimming performance.

Eurasian teal (Anas crecca)

The smallest British waterfowl is a quick and agile surface-feeding duck. The female will lay a clutch of 8–11 cream or pale olive-buff eggs. A group of teal is known as a ‘spring’ because of the way the birds take off vertically, like helicopters.

Common shelduck (Tadorna tadorna)

Colourful birds almost as big as a goose that spend more time on land than most other ducks. They don’t like confined spaces, but are otherwise easy to introduce to a mixed group. The drake emits a clear whistle and the duck replies with a gruff quack. The female prefers to nest in burrows and holes where she lays a clutch of 7–12 eggs.

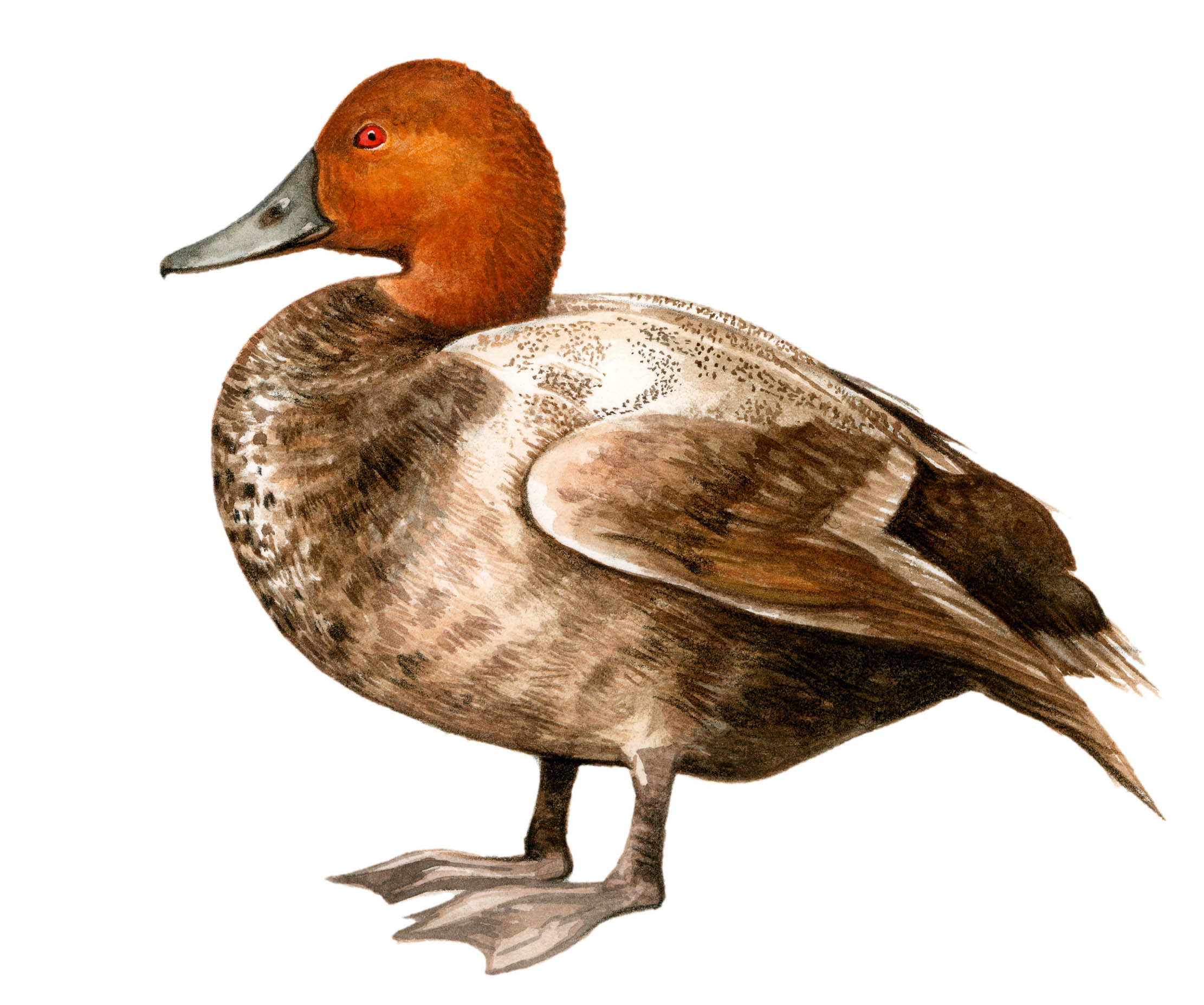

Common pochard (Aythya ferina)

A medium-sized diving duck, not aggressive and easy to keep in a mixed-species captive flock, as long as there is plenty of clean and reasonably deep water. Their short legs set back on their body make walking difficult and they spend most of the time in the water. The females lay about eight green/grey eggs in late spring.

Common goldeneye (Bucephala clangula)

This chunky sea duck gets its scientific name from the soft whistling sound it makes with its wings. It has a varied diet of aquatic invertebrates, insects, small fish and their spawn and some plant matter. Although hardy, they do need some ice-free water during the winter and at least half of their pond should be deeper than 3ft. Drakes like to show off in front of the ducks with a comical courtship dance. Both sexes have distinctive golden eyes, which are visible at long range.

Mandarin (Aix galericulata)

This unmistakable duck puts all others in the shade, with its large orange feathers on the side of its face, orange ‘sails’ on its back and pale-orange sides. Originally from the Far East, where it can still be seen on temple ponds in Japan, the mandarin nests in trees, but is happy to use raised nesting boxes. Part of the drake’s courting ritual involves flicking his head back and softly burping. The drake makes a soft whistling sound and the duck has a gentle quack.

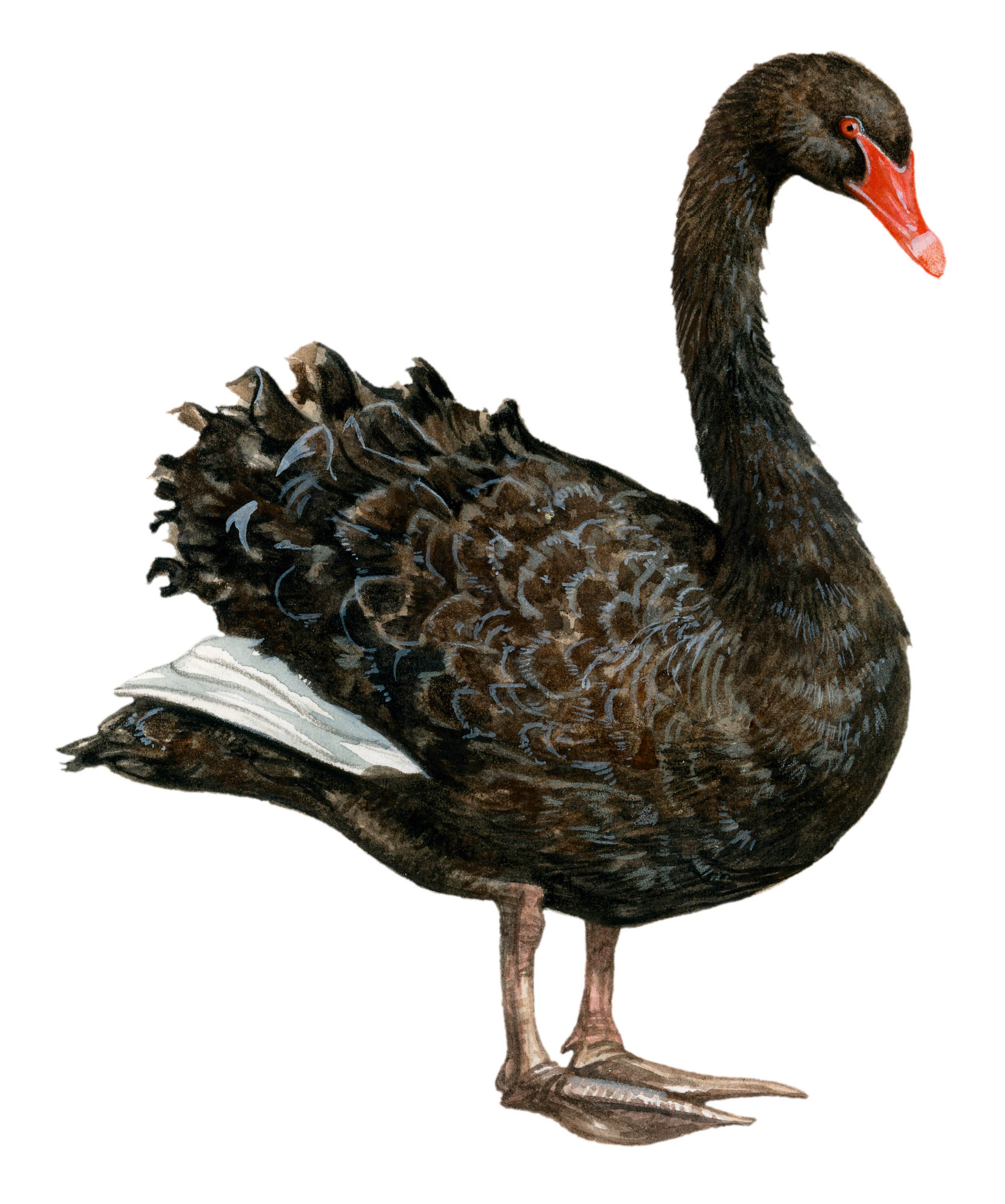

Black swan (Cygnus atratus)

A charismatic adornment to any wildfowl collection, the black swan, which lives wild in its thousands in many parts of the world, is distinguished — as well as by its striking colour — by a proportionately longer neck than other swans. Black swans prefer salt or brackish water and are grazers. Unlike other breeds, they will look for a new mate if one dies.

Nene/Hawaiian goose (Branta sandvicensis)

The official bird of Hawaii is rare and was largely saved from extinction by Sir Peter Scott at Slimbridge in Gloucestershire. They are herbivores that like trimmed grass and, unlike other geese, the webbing on their feet is incomplete. They can be territorial, but breed development has improved both temperament and breeding aptitude. The females start laying — up to five eggs generally — in February.

Shaggy sheep stories: 21 native British sheep breeds and how to recognise them

Here are just some of the breeds to consider, whether for field or table or both.

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

The secret life of sheep — and how these supposedly dim animals show guile, fear, and an ability to pick Fiona Bruce out of a line-up

Condemned as dimwits, could sheep really be the brainiacs of the barnyard, capable of fear, boredom, happiness and identifying Fiona

Vicky Liddell is a nature and countryside journalist from Hampshire who also runs a herb nursery.